Beirut Art Center’s latest exhibition, A Return of the Sun, gathers the works of 14 artists who put violence and its various manifestations under the microscope – from the physically felt to the hidden remnants of past transgressions.

Curated by BAC’s Reem Shadid, A Return of the Sun takes its title from Samih Al-Qasim’s poem Enemy of the Sun; a warning to not passively expect time to heal wounds, but to also trust in time’s ability to lessen pain and grief.

“Through the different proposals of artworks in the show, I was hoping to share questions around various latent or out-of-sight types of violence in our environments, and how to recognise, see or sense them,” Shadid tells Canvas. “How can we start to account for these delayed effects so they don’t remain an omnipresent agent of destruction and loss of life? Who can bear witness to these temporal and spatial calamities, and how do we deploy this knowledge into our present and future conditions?”

Some works in the show reveal insights and propose different forms of representation for the threats identified by Shadid, while others address the larger question of “how to recognise that which lurks in the shadows of time and out of the frame, especially during an unprecedented time of incessant audiovisual media and information overload,” according to the exhibition literature.

The exhibition explores how waste dumps, toxic landfills, the degradation of natural resources and tensions within communities are also forms of violence; often the echoes of a physical act that extends far beyond the end of the event itself, felt for generations after. The artworks attempt to unmask these structures of violence, in order to understand them and do better in the future.

Lebanese artist Christian Sleiman’s A Stretch of Land (2023) looks at a phenomenon expressed by the Greek word pharmakon, meaning both ‘poison’ and ‘remedy’ synonymously.” The work, made up of a series of botanical sketches, plant material and found objects, focuses on the local plant Tayyoun, or Inula viscosa.

“I’ve been interested in foraging for some time now and particularly in how foraging can migrate into the city – how we can practice it in an environment that isn’t the best for plantlife, because there’s a lot of toxicity and pollution,” Sleiman explains. “Inula is a healing plant – the sticky sap can be used on cuts – but most interestingly, it’s among the first species to start growing when the soil has been depleted or suffered damage from human activities. It rejuvenates the soil and encourages biodiversity again.”

Sleiman noticed the plant growing near his studio, near his home – where there is a construction site – and also in downtown Beirut where archaeological excavations had occurred. He tested the soil in these locations for heavy metals, to show the conditions in which the plant thrives.

“In the exhibition are drawings from these three different sites, some samples of the plants, and the data describing the setup of each environment,” he says. “You can see hanging paper objects, and these are traces from each location – I made the paper mainly from Inula but also out of whatever I found there that could be used to produce paper.”

Other works on show include Alia Farid’s audio documentation of Iraq’s marshlands and the nature they support, against the backdrop of invasion and occupation. Nadia Bseiso’s photo series Infertile Crescent (2015–ongoing) captures the 180km route of the proposed Red Sea to Dead Sea water pipeline, examining the desertification of the region and the loss of river systems and forests, caused by geopolitical events.

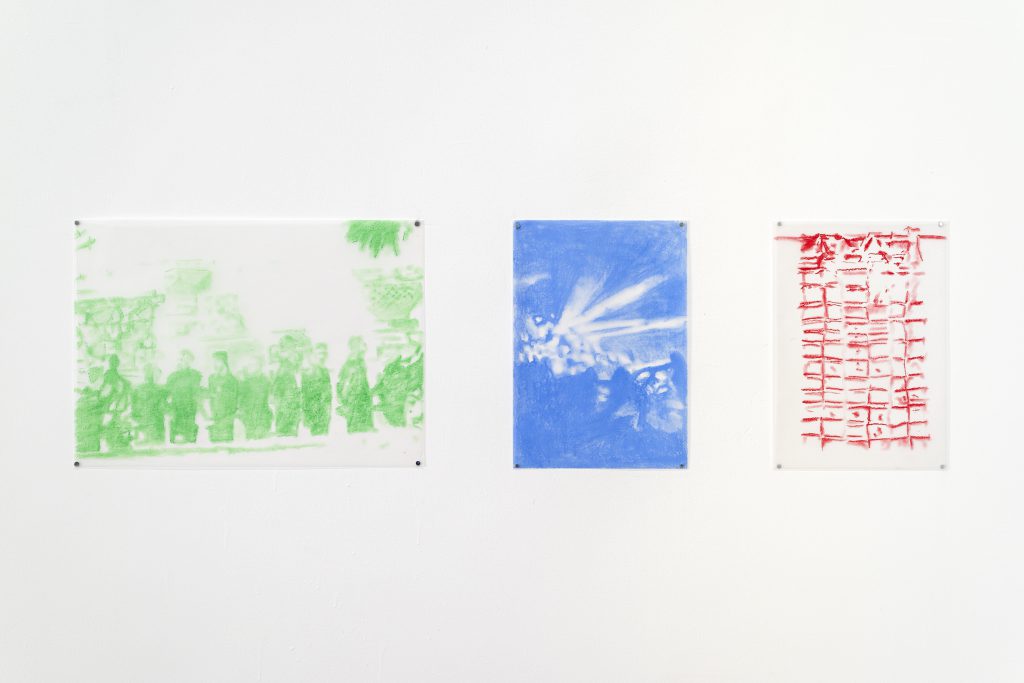

Lamia Abukhadra’s The hammer seizes its actuality (2022) is an ongoing series of drawings and digital prints that questions the normalised image of violence, specifically in social media images that document the daily occurrences of brutality in Palestine.

“These images normally circulate amongst other viral images, where the algorithm creates a context where extrajudicial killings of Palestinian youth compete with cat videos and pasta recipes,” Shadid explains. “It’s interesting to me because it addresses directly this question of how do we break this impasse in visuals that we are facing, or what tools can help us to make the standard image unique again so that it gets the attention and action required?”

Turkish artist Kıymet Daştan presents Oblivion Stones, part of her ongoing project I Am Afraid to (Not) Forget, which she began in 2019 at Ashkal Alwan. The project centres on fake crystals created by melting optical discs – a form of data archival technology that has become obsolete – to highlight the material and metaphorical ties between thick geological layers and today’s sped-up technologies.

The artwork displays gem-like stones with magnifying glasses, turning waste disc materials full of data and memories into precious items of value. Likewise, gemstones must be cracked open and removed from their earthen shell to expose their beauty as a geological time capsule.

“Inspired by the Beirut National Museum and the MIM Mineral Museum, ancient sites and disappearing pirated video stores in Beirut, I traced the way material conditions, human societies and media technologies shape how memory is recorded, preserved, replaced or erased,” Daştan explains. “Optical discs such as DVDs or CDs have lost their memory-carrying function, but are made of petroleum and rare metals such as gold, silver and aluminium. I tried to use as many different varieties as possible in my work, opening up a space for reflection on the material value they have, apart from the value lost due to the dysfunction of the discs,” she adds.

A Return of the Sun runs until 16 September 2023