As Noor Riyadh celebrated its third edition, The Bright Side of the Desert Moon offered a coherent and contemplative suite of works that proved well positioned to our times.

As Saudi Arabia’s art express hurtles ever onwards, there are signs that a particular junction may have been reached for Noor Riyadh, one of the shiniest stars in the Kingdom’s cultural cosmos. As in life generally, less can often be more. So it was that the third iteration of what is billed by organiser Riyadh Art as “the world’s largest light art festival” was scaled back from last year’s ambitious extravaganza, which saw such a bewildering array of works in so many different locations that it bordered on the overwhelming. The time and effort involved in moving around, invariably by road, between the many (as in, 40) sites precluded even the most dedicated art seekers from experiencing everything available.

This year, there were just five main hubs and a general sense that what was on offer, and where, was more realistically matched to the logistics of a city that now boasts over 7.5 million inhabitants and increasingly chronic traffic congestion. Under the auspices of lead curator Jérôme Sans and curators Pedro Alonzo, Fahad Bin Naif and Alaa Tarabzouni, The Bright Side of the Desert Moon (ended 16 December 2023) showcased more than 120 artworks by over 100 local and international artists. The festival’s central hub was the King Abdullah Financial District (KAFD), alongside JAX, the Saudi capital’s contrived but undeniably successful arts district, and the more expansive locations of Wadi Namar, Wadi Hanifa and Salam Park.

Exploring the works in the wadis last year was a trial for some visitors, with periodic overcrowding and confusing access points (sometimes exacerbated, rather ironically, by poor lighting). No such problems this year, which saw a great improvement in terms of visitor management and clarity of route, perhaps the result of the curators being more holistically involved in the presentational context of the works they were curating. In Wadi Namar, one of the most immediately engaging installations was Still from here (2023) by PHI Studio (Saeed Gebaan and Hatim Al Ahmed), an interactive work that harnesses the traditional desert knowledge of the Bedouin and interprets it to a wider audience via a sceptre and luminous floor where viewers can draw in the sand. Visitors swarmed around, transfixed on making their own marks. “The nature of the lifestyle embraced by Bedouin societies, especially the concept of mobility, has had a major impact on our work”, says Gebaan. “We are especially interested in the documentation of knowledge and how contemporary artistic practices can help save this heritage.”

The idea of the desert as a conduit for movement and change through light also had a presence in Wadi Hanifa, where Zahrah Alghamdi’s stunning Life (2023) offered a mini-city of sculpted backlit epoxy dunes in a ‘Hegra meets Manhattan’ moment. Not far away, the power of the virtual versus reality was elegantly explored in a site-specific untitled piece by Khaled Makhshoush. His LED screen billboard and animated pixel frames, complete with glitches, offered a playful impression of the very view it obscured – in this case of a large bridge spanning the wadi. “I wanted to depict the landscape behind the screen,” says Makhshoush, “to show an alternative way of looking at a place or environment.”

The drama of experiencing epic art alfresco is, hopefully at least, complemented by the intimacy offered by the festival’s indoor exhibition. This edition’s show – Refracted Identities, Shared Futures – is once again presented in the Riyadh Art space in JAX. Curated by Neville Wakefield and Maya Al Athel, it features works by over 30 artists, mostly special commissions and some coping with the constraints of the space rather better than others. Standouts include Lachlan Turczan’s fabulously winnowing work, Wavespace (2023), which explores the idea of sound as liquid light; Abdulmohsen Al Bin Ali’s lyrical The Dreamer Dreams (2023), an enchanting evocation of fast-disappearing Arabian folklore; and It’s Really Hard to See From Here (2023), an intriguing video of a heat-reactive thawb by Ahaad Alamoudi, whose magnificent performative installation from Noor Riyadh last year remains a talking point. Elsewhere in JAX, notable festival works included Muhannad Shono’s Absent Sky (2023) and the quite outstanding News From Nowhere: Eclipse (2022–23) by Moon Kyungwon & Jeon Joonho, a video piece presented in a LED-lit jail-like grid and focused on a man lost at sea in a lifeboat that is also his paradoxical prison.

Three years in, and there’s a confidence in the air that Noor Riyadh now has such sturdy legs of its own that it is in no need of being judged against other similar, sometimes more longstanding, events. “We’ve reached the point where the comparative points of reference no longer have relevance,” says exhibition lead curator, Neville Wakefield. “We have our own light and our own space, and that’s what this show is all about.” At the exhibition preview there was much talk of “inclusivity”, “transformation” and “democratic spaces”, as well as of new dawns in terms of the role of technology in communication. “Light is the new ink,” continues Wakefield. “We are at a Gutenberg moment.”

Ahaad Alamoudi. It’s Really hard To See From Here. 2023. Photography © Noor Riyadh 2023, a Riyadh Art Program. Image courtesy of the artist

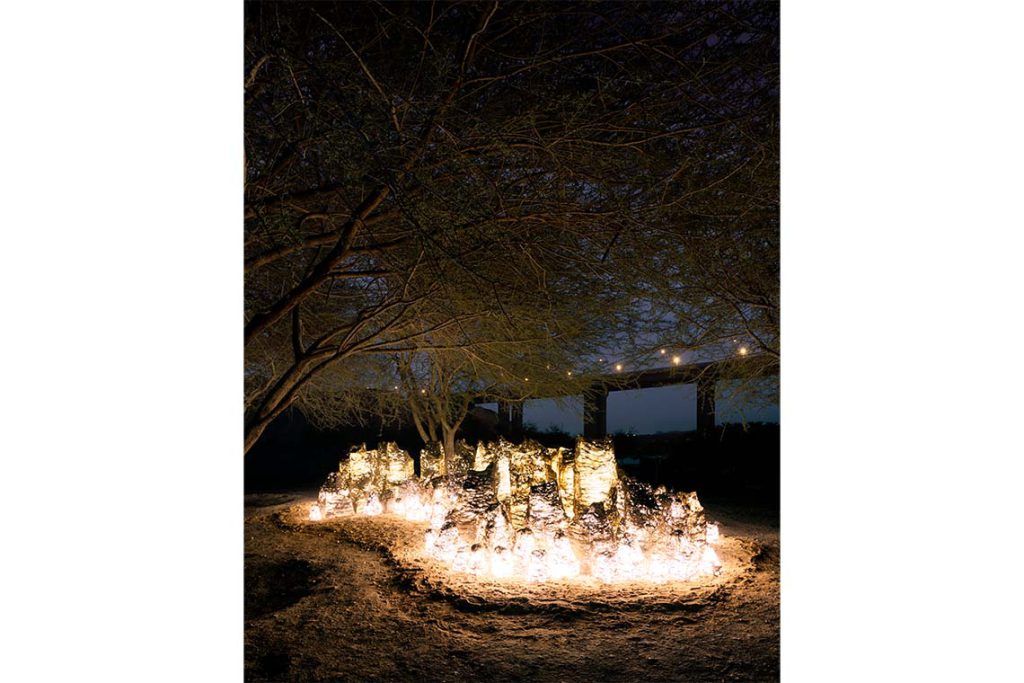

The sceptical might say that such a moment has been upon us for some time already, but there is no denying that Noor Riyadh 2023 articulated the growing maturity of the Saudi art scene. With the fanfaring over, the real work is underway. Chris Levine, whose splendid Molecule of Light (2021) in Wadi Namar marked the artist’s first engagement with the Kingdom, quickly appreciated the magic of what is happening. “I knew instantly that the wadi setting was perfect,” he said to Canvas. “The piece works just beautifully there and to see the beams play out over the rock structures and textures was breathtaking. On the opening night, the full moon cast a perfect concentric shadow of the structure and a handful of us stood in alignment. We felt we were witnessing something quite profound, beyond what I might describe in words. The festival is epic, unlike anything I’ve ever attended. I think this is a significant cultural moment in Saudi Arabia and I’m humbled to be a little part of it.”

Refracted Identities, Shared Futures runs until 2 March 2024

This review first appeared in Canvas 111: Crafting the Contemporary