Under the curatorship of Danielle Makhoul, slow burn examines fire as both a destructive force and a latent, simmering state of being.

For Beirut Art Center’s latest exhibition, the team issued an open call inviting artists from Lebanon and the wider region to explore the concept of fire. This classical element – often used to represent themes of destruction, instability and transformation – is linked to the political, social and cultural forces at play in the Lebanese environment; in the past several years alone, the country has experienced a series of devastating crises. The economic collapse, Covid-19, the 2020 Port Blast and Israel’s war on Lebanon have all left destruction in their wake. Furthermore, the ongoing nature of these circumstances has also made it difficult for artists to create permanent, static pieces of work. As a result, a fascinating curatorial decision was taken: the theme of fire would be explored through the process of creation itself.

Nine of the selected 20 artists relocated their studios to Beirut Art Center, with visitors invited to observe their processes of creation. Vivid paint strokes, melting materials and creative conversations played out in front of the audience. Left to the fate of current events, the individual artist’s surroundings and the unfolding collective process, each piece transformed accordingly. For those unable to relocate, constant communication was encouraged to ensure an interconnectedness in the exhibition. The resulting body of works, entitled slow burn, came to embody the interstitial state of fire – controlled and latent, but holding the same destructive potential as fire. slow burn is a condition that hovers in a state of becoming.

The charged atmosphere of the exhibition is established by the very first piece, I’ve killed too many birds with concentrated sun beams (2025) by Elie Mouhanna. Aluminium foil cut-outs line the wall, representing the Ashalim solar power plant station in the Naqab desert in occupied Palestine. The reflective squares glimmer at the viewer, individual cut-outs occasionally protruding, scraps of foil layered on the surface as though some elements have had to be repaired. The glittering surface, possessing the ability to both harness the sun’s power and reflect its light, forces the viewer to reflect on themes of life and annihilation.

Destruction is also explored through Afram Chamoun’s Power Station (Jiyeh) (2025). Working across oil on canvas and a pencil drawing sketched onto the wall, Chamoun’s works are based on a power station destroyed in 2006. The painting, permanent and static, contains a rumbling presence, pointing to the massive size and strength associated with the station. In contrast, the sketch undercuts this sense of vitality. Soft grey pencil strokes, which will inevitably be erased, point to the fragility and vulnerability inherent in destruction. A few steps away, Black Cloud (2016) by Abdelrahman Abo Lela hammers the point home. Photographs depict the plumes of smoke created by the burning of rice straw in the Nile Delta of Egypt. Here, fire is a helpful short-term destructive force that gives way to a deadly slow burn in the form of latent, pervasive health issues for local communities.

The pervasiveness of violence is explored throughout the works on the ground floor. Nadine Kerbaj’s series of paintings, How Do We Look At Spring Fires Today? (2025), portrays the blazes instigated by Lebanese farmers to renew the soil for the next harvest. Whilst depicting a controlled fire, the destructive nature of the dark clouds, rising above verdant landscapes, still appears violent. The images are particularly poignant in terms of their context; visitors are immediately reminded of Israel’s ongoing attacks on Lebanon’s mountainous Beqaa region. This sense of unending annihilation is only amplified by Salah Missi’s untitled work and Mayssa El Khoury’s Nocturne (both 2025). The former features broad swathes of pastel on paper, depicting flames and ashes enveloping the Mediterranean landscape. In the latter, similar scenes of destruction can be seen, with argyle ash used to depict the burn of shisha coals. While the flame appears all encompassing, both pieces remind us of what is left behind in the charred remnants. It is in these ruins that grief is left to simmer.

Upstairs on the mezzanine level, the latent and charged nature of slow burn turns further inwards towards bereavement. Tamara Kalo’s The only body capable of holding our world’s grief (2025) is made up of a lumen photograph stretched across 20 tiled sheets of paper. Exposed over three days, the piece captures the shifting passage of sunlight across the corniche of Saida. Fragmented and ablaze with light, the sea is depicted as the only space large enough to contain collective grief. Nearby, a mixed-media installation of acrylic on nylon sheets hangs from the wall. The interplay of light and shadows illuminates certain aspects: a crab, an olive tree and a phoenix come into focus against blazing flames. Curiously alive with movement, collective loss and mourning appear as an interconnected force of reckoning in Tala Asmar’s Where the Sea Was (2025).

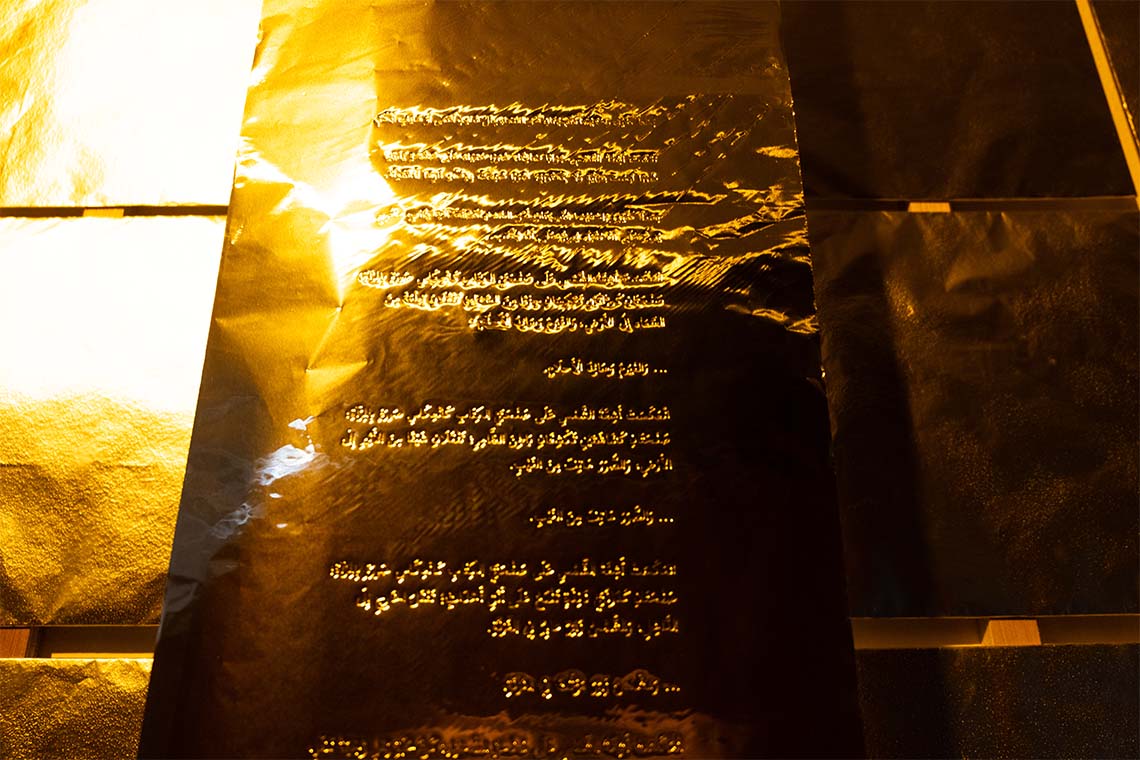

The final work confronting visitors is Schism (2025) by Aya Nadera Zantout, one that they have already seen. Made from acrylic on cotton fabric, the cloth is draped over the mezzanine level and pools on the ground floor. Upstairs, we see the first half of it stretched across the ground. Scribbled verses are repeatedly etched on the cloth following the passing of Zantout’s grandmother and the annihilation of her home by an Israeli missile in 2024. Each excerpt comes from a poem the artist’s Palestinian grandmother learned at school in Yafa: ‘My mother, whom I love’, ‘Beside her my happiness’, ‘For me is a home in her heart’ and ‘Does not cease until death’ cover the piece. The lines, repeated over and over again, appear both meditative and relentless. Through this work, portraying both forcible destruction and grief, Zantout adeptly distils the notion of a slow burn: latent, unceasing and all-encompassing.