Zilberman Istanbul is delighted to announce the group exhibition titled Settling into the Abyss curated by Naz Kocadere. Bringing together works by Isaac Chong Wai, Sandra del Pilar, Memed Erdener, Erkan Özgen, Yaşam Şaşmazer, Neriman Polat, Cengiz Tekin, and İsmail Yılmaz, the show is open to visit at the main exhibition space of Zilberman Istanbul at the Mısır Apartment between May 13 – July 1, 2022.

Contrary to common opinion, is the devil not in the details, but in sight, and does it rest closer to us than we think? Having written “Sympathy for the Devil” with Keith Richards, Mick Jagger sings in first person as satan, documenting historic events that could be seen as the devil’s works. The song was intended to present an analysis of the dark side of humanity, one which allows itself to be too easily swallowed up by the banality of evil. If we understand the devilish mechanisms within ourselves we can deal with it. The exhibition Settling into the Abyss, which examines people’s tendency to violence and darkness through the relationship with the individual, society and nature, takes its name from Friedrich Nietzsche’s Beyond Good and Evil (1886), referred to by the artist Memed Erdener. In Nietzsche’s words, “Whoever fights monsters should see to it that in the process they do not become a monster. And if you gaze long enough into an abyss, the abyss will gaze back into you.” In this context, “gazing into the abyss” refers to the fact that contemplating something foreign to one’s self may bear dark consequences for the self.

The exhibition deepens around the notions of representation, identity, grief, justice, solidarity, rebellion and psychological dilemma. Following the readings on the psyche, Carl Jung is among the scholars who enrich the framework of the exhibition. The “shadow” is a concept first coined by Jung, describing the unknown aspects of the personality that one chooses to reject and repress. The shadow archetype corresponds to the unearthing of shady parts within one’s unconscious mind and the process of acceptance of traumas in pursuit of an inner peace. Yaşam Şaşmazer’s sculpture dwells on such investigation within the human psyche through a matriarchal approach. She portrays a figure that dares to confront the darkness within her soul and what’s more, finds peace after all.

From another perspective, Sandra del Pilar presents a staggering and realistic portrayal of an ensemble of intertwined individuals. She depicts a critique of the societal norms of stigmatization through usage of transparent layers of color and fabric. Jacqueline Rose expounds the personal and the political juncture in her feminist research practice. Rose argues that when determining where violence derives from, a faulty division between the inner (personal) and the outer (societal) margins is made which are quite the contrary, actually inextricable. Through her studies on violence, gender and psychoanalysis, Rose stands against a dual unbundling that positions two separate sides such as the victim and the attacker. An example of such inseparability could be seen in Erkan Özgen’s video art accompanied with a photo installation. Özgen points out to the malfunctioning of imposed communal history-making and its rootless reciprocity in the individual. He displays how the actuality reveals the irony of nationalism and its dangerous enforcements to praising violence.

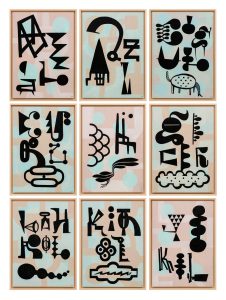

In other respects, in her book titled The Force of Nonviolence Judith Butler explains how power structures falsify the vocabulary concerning violence and the resistance towards it. Butler’s words that claim “nonviolence as an ongoing struggle, not an absolute principle” echo in Memed Erdener’s nonuple painting. Memed proves that the fact that political opposition and criticism-oriented efforts are frequently labeled as “violence” by the state authorities, which are seen as a threat, shall not cause one to abandon hope from language. In a similar vein, Neriman Polat monumentalizes a requiem built to commemorate the lost lives due to the violence against women. In his fictive-photographs, Cengiz Tekin stages the subtle yet violent representation of the identity that is tightly surrounded by the geography, the history and it’s politics. Tekin’s questioning of one’s stance to another’s pain is in dialogue with Isaac Chong Wai’s installation. Chong Wai puts forward the frozen traces of violence and unveils the prominence of one’s choice to remain indifferent or not towards past sufferings. Lastly, İsmail Yılmaz documents an individual’s inner exploration through nature, bold and prepared to confront whatever beast he might come across in the way. After all, perhaps one shall not solely gaze into an abyss but rather go right into it to confront and make peace with it.

The life-size painting “Who am I and How Much?” (2019) by Sandra del Pilar depicts a group of figures intertwined in each other or drawn on top of each other on different scales, labeled with dollar prices as in a window display. The artist Sandra del Pilar asks: “How do we evaluate a human being today, in an era in which everything is expressed in terms of monetary value?” In an attempt to make such an inquiry, Del Pilar focuses on something that is beyond the visible; on what can’t be seen, but nonetheless persists within the imagination. When looking at the work, the observer is often overstrained by a wealth of details and the eye, as well as the reason, reaches its limits. The viewer perceives fragments which belong to multiple image layers. The first layer is the oil painting on canvas over which the artist stretches a layer or several layers of transparent synthetic material. Transparent layers are painted in part, elements are repeated from the first layer, or new image elements are introduced. Whilst looking at the painting, the viewer shall move back and forth in order to fully experience it. The relationship between the layers moves the focus beyond each layer and activates the sense of touch. In this way, the artist enables the viewer to establish a somatic relationship with the painting. Meaning is no longer produced solely through imagery; bodily materialities become carriers of meaning.

Memed Erdener’s work titled “The Nonuple of Rabid Minority” (2021) consists of words that the government ascribes to independent people who refuse to be a part of the mass and remain distant to the discourses of the media, the temple, and politics, whilst managing to remain singular. The artist uses three methods to create these nine transcripts.

I) calligram: letters that form a picture.

II) peer-type letter: letters that refuse to differentiate, wishing to remain the same as the others.

III) letter-likes: letters that refuse to be the same, wishing to differentiate from the others.

The title of each work in the painting, written from left to right:

1. Rabid Minority (calligram)

2. Foam bather (homogeneous letter)

3. Fund-taker (letteresque)

4. LGBTist (homogeneous letter)

5. Remnant of the sword (calligram)

6. Of bad stock (homogeneous letter)

7. Istanbul conventionist (letteresque)

8. Organized immoral (homogeneous letter)

9. Mindset of the secularist (calligram)

Erkan Özgen shot the video titled “The Memory of Time” (2018) on the Finnish group of islands Suomenlinna: a fortress surrounded by ancient cannons that were used in wars that raged centuries ago. UNESCO has designated the island as well as the cannons as cultural heritage, claiming the site as housing valuable historical artifacts dating back to the time when the weapons were used by the army during wars of a century ago. In Özgen’s video work, tourists visiting the island consider these military guns as cultural treasure, taking commemorative photographs with cannons and storing them in family albums. The artist simply observes these scenes with his camera, whilst posing provocative questions to tourists on the island. Thus paving the way for people to face their problematic relationship to the weapons, “The Memory of Time” raises the question of whether weapons that cause so much suffering today will also be considered valuable heritage that needs safeguarding in the future. Erkan Özgen’s “The Memory of Time (2018)” is accompanied by a set of eleven photographs, which showcases a cozy layout, reminiscent of commemorative photographs, such as postcards.

Yaşam Şaşmazer created the sculpture titled “Sleep” (2013), which is part of her Metanoia series, inspired by the Shadow Archetype theory of Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung, the founder of analytical psychology. The artist derives from the idea that shadow is seen symbolically as dark, unconscious, forgotten and suppressed parts of the individual. Inviting people to face their inner fears, Şaşmazer highlights the main subject of the work as the black shadow. In addition to being one of human’s greatest phobias, this shadow depicts a spider that points to a creative as well as a confining potential due to its web-weaving ability. The spider figure, which has deep symbolic roots, also reminds the viewer of ancient wisdom, matriarchy, femininity and the maternal complex in history. From this point of view, the young woman sleeping in the belly of a spider in the sculpture, together with her fears, stages an individual who is unconsciously at peace. “Sleep” describes one’s spiritual maturation, along with an acceptance of the dark and shadow sides.

In her work “Flower Wound”(2019), which is a site-specific installation, Neriman Polat places meters of flannel, pink floral fabric to cover the space like a Baroque curtain. The work acts as a requiem for women who have been embroidering their pain and suffering on fabric for a long time. Created by the artist by pulling the threads of all the flowers on the fabric one by one, the installation focuses on femicides, which leave trace even after forming a crust, the mourning for which never ends. While confronting the viewer with a monument with the wide space it occupies, it reveals the actuality of painful aspects of life such as physical and emotional injury, death and (restrained) mourning.

In the exhibition, three fictive-photographs by Cengiz Tekin titled “Panorama” (2007), “Still Life” (2007), and “Untitled” (Fume) (2010) are on display. “Panorama” is reminiscent of a scene depicted by the 19th-century German romantics*; a figure standing on a rock in his coat watches the horizon. Although the landscape which the figure watches presents a romantic nature, “the politicized geography does not allow much for romance” in Tekin’s photograph. This male figure has a lifeless male body under his feet, even though he does not carry a trace of blood. Among the highlights of the photograph are the unsolved murders that frequently occurred during Tekin’s years in Diyarbakır; dirty wars caused by nationalist policies; and the political violence and helplessness that fails to encounter the grieving process that comes with a loss.

In his fictive-photo “Still Life”, Cengiz Tekin shows the famous wheat fields of Diyarbakır with reference to the Dutch painter Van Gogh’s painting “Wheat Field and Crows”. In the photograph, a dead figure is seen, possibly dead, lying face down amidst dried grass, that is, still nature. The blue-dressed figure is similar in color to the sky, suggesting its fall from the sky. But then, the gun in the figure’s hand hints the possibility of a suicide or a gun-fight scene. The artist describes this landscape as a geography where the rural landscape is identified with death rather than tranquility, where unsolved murders, also defined as the dark years, are made clearly visible in the raw sunlight without distinguishing between day and night in this “still life”.

In the photograph titled “Untitled (Fume)”, two young men are tracked in the middle of a barren field. One points to the horizon, to a cloud of black smoke rising from a distant field. Their casual stance implies that they are more interested in the mysterious smoke in the distance than the destruction surrounding them. A burning house or field in the distance of rising smoke; or whether it was a destructive act or just a farmer’s agricultural waste. The body language of the figures, which follow what is happening in a haphazard manner and are not in a hurry to act, reflects the artist’s critical language about the experiences of individuals living in a war-torn region. Wherever we are as viewers, what is our distance and drive to get closer to the destruction that surrounds us?

“Missing Space”(2020), delicate amorphous glass sculptures by Isaac Chong Wai, echoes the fragility of violence. Constructed as an installation, the artwork consists of bullet holes with GPS numbers mounted to find locations, a hidden past dragging into the present. Displayed on mirrored surfaces, the glass sculptures are the casts of bullet holes from the walls in Berlin. Transforming the absence of the body into a symbol of life, the artist freezes instances of violence through the usage of a fragile material as glass. Violence leaves traces: on our body, in physical spaces and in our mind. Chong Wai emphasizes that indifference to violence would only mean acting as an accomplice in the crime. Indifference is more violent than one might think; it becomes the act of participating in the erasure of a crime’s existence.

İsmail Yılmaz describes the story of an individual’s search for his inner world with an autobiographical narration in his fictive-photo series titled “Returning Home”(2019). In the series, the artist shows that this journey takes the person to places where time and space are uncertain, to nature. In the compositions he staged in nature, everything is in its place and in its own way, reminding Yılmaz that the figure is a part of nature. Photographs that present the harmonized relationship between human and nature pave the way for exploring the dark and light aspects of the inner world of the individual.