“The act was a crime against Assyria, against Iraq, and against humanity. Destroy the past, and you control the future.” —Tom Holland

Green Art Gallery is pleased to present Michael Rakowitz’s first solo exhibition at the Gallery, following his large-scale institutional exhibition at the Jameel Arts Centre in Dubai in 2020. He has shown regularly at Sharjah Art Foundation including mostly recently in Sharjah Biennial 14: Leaving the Echo Chamber (2019) and Unsettled Objects (2021) at the Flying Saucer. His work will be included in the upcoming Sharjah Biennial 15: Thinking Historically in the Present, opening February 2023.

The invisible enemy should not exist is an ongoing project centering on threatened, destroyed, and missing cultural heritage. Michael Rakowitz began this work in 2007, reappearing artifacts looted from the National Museum of Iraq in the aftermath of the US-led invasion in 2003. Drawing from a database of reference images and information, the sculptures are constructed using papier-mâché made of Arabic-English newspapers and West Asian food packaging found in diasporic grocery stores in Chicago. The invisible enemy should not exist is a translation of “Aj ibur shapu,” the name of the Processional Way that ran through Nebuchadnezzar’s Ishtar Gate in Babylon.

Included in this exhibition is a series of cylinder seals. Existing on an intimate scale, cylinder seals were small stone objects that were rolled out onto wet clay to create an impression. They are linked to the invention of cuneiform writing on clay and were used as signatures, worn around the neck as jewelry, and served as amulets. Before the Iraq Museum’s looting, the collection of seals was over 15,000.

In 2018, Rakowitz began a new branch of the project. Since the mid-1800s, Western institutions like the Louvre, the British Museum, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art have participated in the systematic extraction of works from the Assyrian Northwest Palace of Kalhu, (Nimrud), near present day Mosul, Iraq. The sculptural relief panels that remained after these waves of excavations were destroyed by ISIS in 2015. Using the same logic of the first iteration of The invisible enemy should not exist, Rakowitz and his studio have been reappearing the 200 remaining panels of the palace that were in situ until their destruction in 2015. Each room of The invisible enemy should not exist (Northwest Palace of Kalhu) is installed true to its original architectural footprint. As an integral part of each room’s installation, empty spaces with museum labels indicate where the panels that still exist are held, mostly in private collections or museums in the West. These empty spaces of imperialist extraction, alongside the reappeared panels that remained in the palace until their destruction in 2015, provide a view of what the palace would have looked like the day before its destruction by ISIS, and make present the human lives that perished alongside the destroyed archaeological sites. It is a project that acknowledges the continued history of displacement in Iraq, creating a palimpsest of different moments of removal.

Premiering at Green Art Gallery is a section of Room S from the Northwest Palace of Kalhu. This room was a reception hall containing one of the most carefully constructed and well preserved reliefs depicting King Ashurnasirpal II, which was excavated by Austen Henry Layard in 1847 and sent immediately to the British Museum. The exhibition features the first group of reliefs in this ongoing series to include within the papier-maché collage fragments from old issues of Nineveh Magazine, quarterly publication in Modern Assyrian and English generously donated to Michael Rakowitz’s studio by the Assyrian Foundation of America.

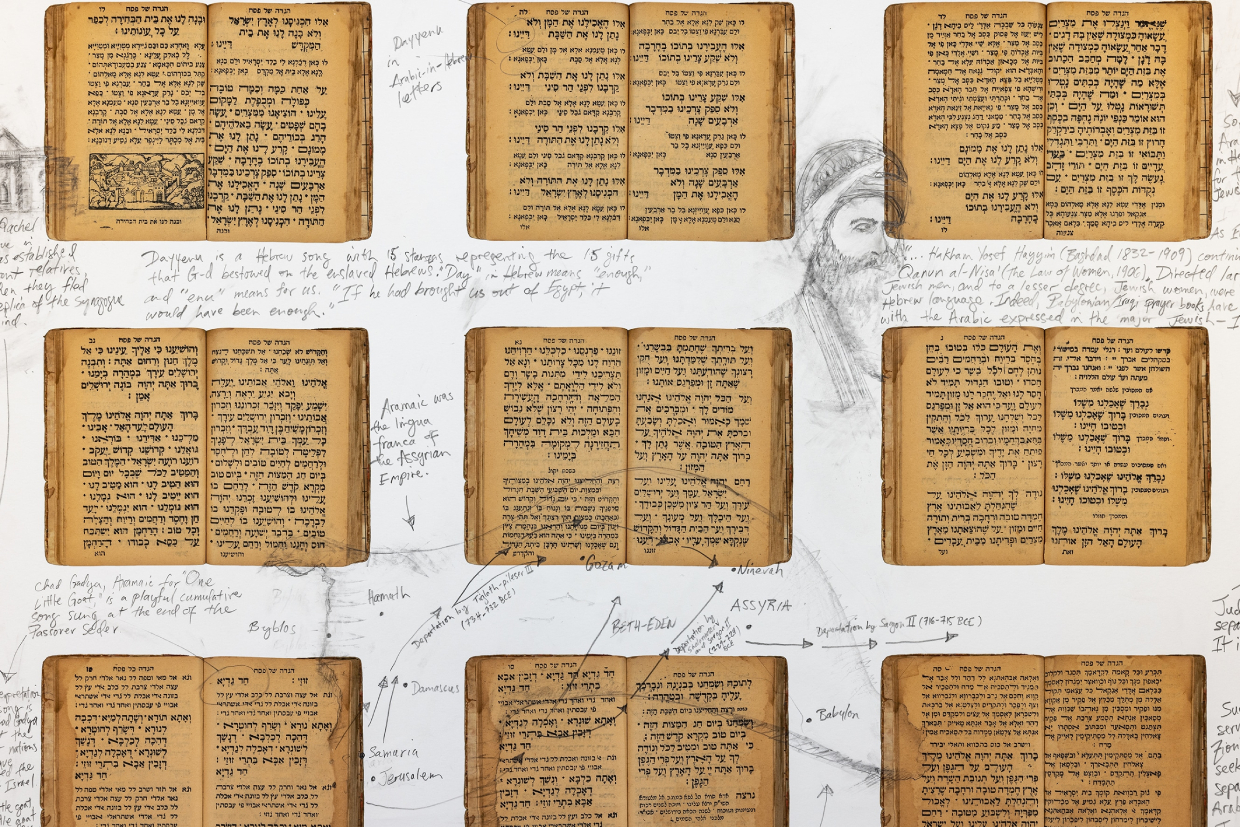

The exhibition also includes Rakowitz’s Charita Baghdad, a site-specific intervention in dialogue with Rigas Feraios’ Charta of Greece. This ongoing work consists of an annotated 1936 Passover Haggadah belonging to the Baghdadi Jewish community in what is now modern day Iraq, from where the artist’s maternal family is from. Conceived in continuing conversation with Dr. Ella Habiba Shohat, a cultural theorist descended from a Baghdadi Jewish family, Charita Baghdad interrogates the linguistic confusion around the existence of “Judeo-Arabic.” While there exists a dialect one can say is specific to the departed Iraqi Jewish community, what emerges from the page-by-page reading of this prayer book is more complex, shedding the simplistic view that Judeo-Arabic was like a West Asian version of Yiddish, partitioned from Arabic. In fact, the book is written with liturgical Hebrew prayers, but with instructions and translation in Arabic-in- Hebrew letters. This illustrates how literacy (reading and writing Arabic) was not accessible to all at this time, and thus education came through the community hub that was the synagogue during this era. Arabic-in-Hebrew letters functioned simply as a transliteration of the lingua-franca of Baghdadi Arabic. At stake in this study is the contested identity of the Arab-Jew which is rejected by Jewish nationalist ideology. As Shohat writes in The Invention of Judeo-Arabic, “the inclusion of Judeo-Arabic in the ‘family of Jewish languages’, standing always already apart from its (non-Jewish) Arab neighbors, thus reveals another facet of the question, i.e. a Jewish national allegory in which for Jewishness to exist Arabness has to vanish, and then be resuscitated as essentially Jewish.”