On the heels of the announcement of an Abu Dhabi edition of Frieze in November 2026, this year’s London fair hints at a growing footprint from the region.

In a landscape where the distinctions between commercial and non-profit are gradually blurring, one benefit of the loosening of the definers is the parallel expansion of geographies that art spectacles cover. In comparison to the 1990s, or even a decade ago, art fairs, biennials and other blockbuster affairs embrace a widened roster of participants hailing from markets and creative hubs deemed supposedly unfeasible or opaque by dominant Western codes.

“Biennials were more of the backbone of the art scene in the 90s, because they were the places where we could see postmodern avant-garde art or socially engaged practices,” says Frieze Sculpture’s Turkish-born and London-based curator, Fatoş Üstek. “Today, there is an amalgamation of entities. Everything has become more porous in the sense that biennials sometimes act like art fairs, not only because they get the majority of their support from commercial galleries but also because of the way in which they draw attention and press coverage.”

Yet again, among the basic tenets of a sizeable art fair like Frieze London is the plethora of international galleries promising new discoveries for the jaded eyes of mainstream fairgoers. This year’s edition offers a compact-but-fruitful group of Arab world exhibitors, showcasing material- and process-focused artists who deliver far-reaching statements through observations of their own lands at different paces.

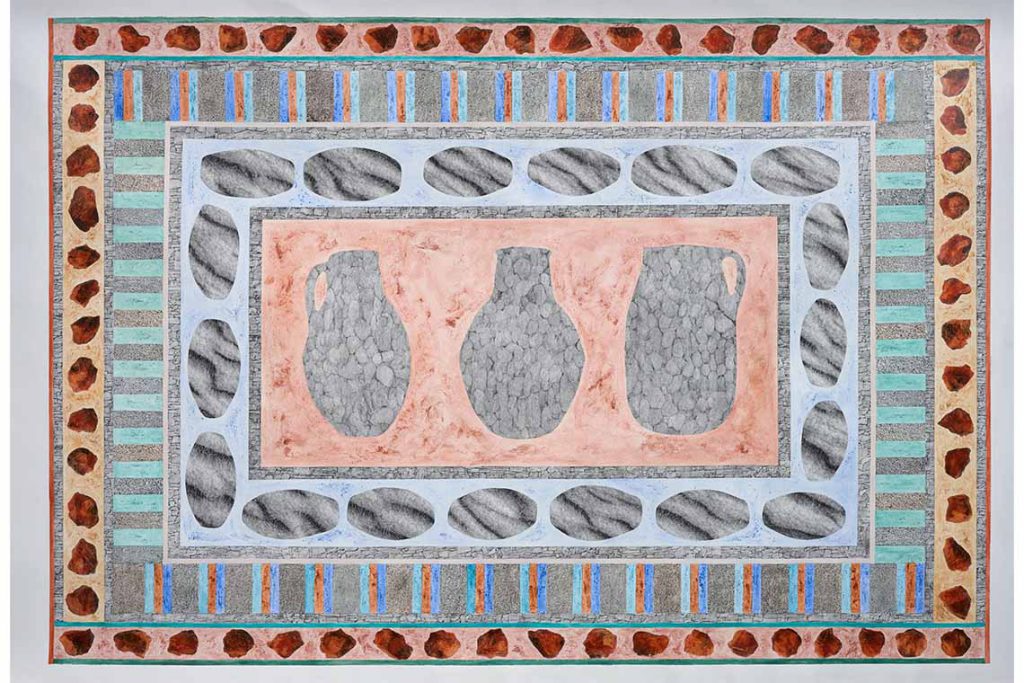

107 x 182 cm. Image courtesy of the artist and ATHR

Üstek’s sculpture project is an ideal example of the entanglement between the binary worlds of commercial and not. The fair’s complementary public leg is open free of charge to Regent’s Park visitors for longer than the fair’s half-week run. Among this year’s 14 large-scale, mostly commissioned, outdoor sculptures is Neighbours (2025) by Iranian artist Abdollah Nafisi, who has recently graduated from the Royal College of Arts. Üstek lectures at the college and selected the young artist through Dastan Gallery’s submission to the annual open call for Frieze Sculpture. In line with this year’s theme of In the Shadows, Nafisi’s orchestration of two large horns, facing each other through their openings, captures and suspends an invisible force. Silent but somehow sonic, the sculpture – created from pieces of waste steel and fallen trees – cries an ode to any fleeting second and invisible cacophony.

At the main fair, Dastan presents a multi-artist booth with works by Reza Aramesh, Farah Ossouli, Soheila Sokhanvari, Maryam Ayeen & Abbas Shahsavar, Shahryar Hatami and Morteza Pourhosseini, who all explore corporality, either viscerally or allusively, in the hectic setting of a fair. “We were intrigued by how a shared form, something so universally recognisable, familiar and relatable, could serve such distinct purposes,” says Ashkan Zahraei, the gallery’s artistic director of international programs, who thinks the two artists’ work “intertwine mythology and the present, history and timelessness.

Myths embodied in the physicality of a land is central to Daniah Alsaleh’s works on paper, which occupy Saudi Arabia’s ATHR Gallery’s booth alongside Basmah Felemban’s ballpoint drawings of marine life. Alsaleh’s images possess ground carnelian collected from AlUla, where these stones have been used for millennia, through consecutive civilisations. “What fascinated me about carnelian is how persistently it appears across time in the archaeological sites of AlUla,” says Alsaleh, who came across an excavated carnelian bead workshop dating from over 3000 years ago in the ancient city. Fascinated by the material’s insistence on existing as a form of persevering beauty, she transforms the stone into pigment to illustrate serpentine figures over drawings of meditative ancient sites. It is “a way of translating that sense of continuity, as well as the mystery of something ancient still pulsing beneath the surface,” she explains.

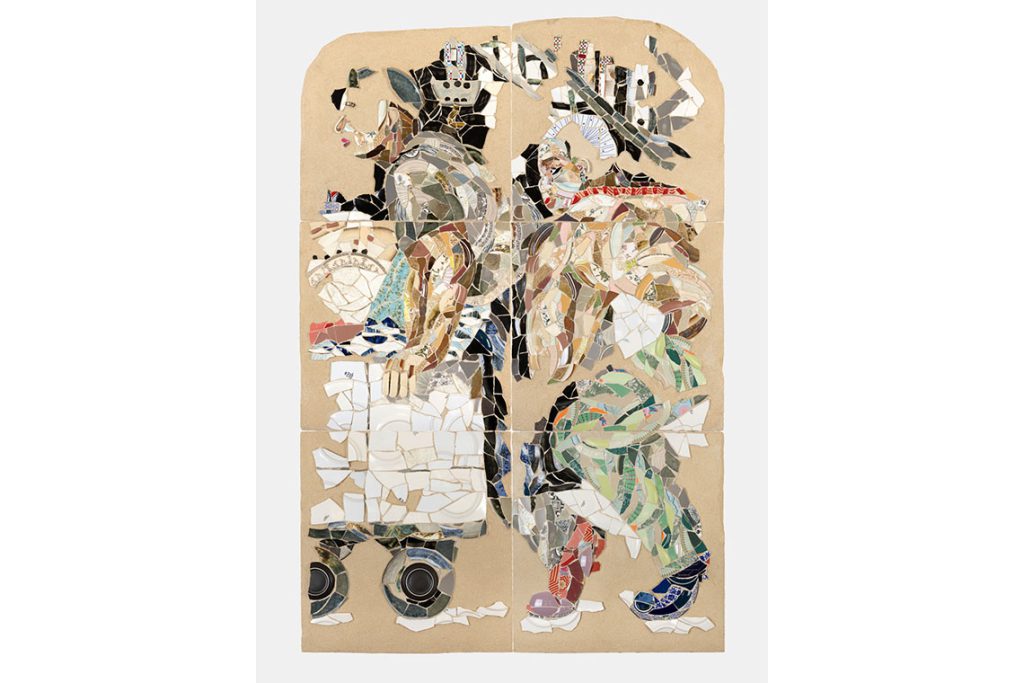

Cairo’s Gypsum Gallery also delivers a two-artist presentation with a joint focus on Alexandria as a city of knowledge, commerce, and pride. Destruction, only to rise anew, anchors Yasmine El Meleegy’s wall reliefs. Their fragmented charm stems from the artist’s utilisation of remnant shards from celebrated 20th century Egyptian sculptor Fathy Mahmoud’s porcelains which El Meleegy transforms into gently chaotic and subtly figurative juxtapositions. Factory workers and fishermen around the Port of Alexandria who were Mahmoud’s subjects reappear in her reliefs as re-evaluated and valued, occupying the surfaces with grand presence. “Both Alexandria and London are port cities historically shaped by trade, migration, and layered cultural identities — cities where commerce and empire have left deep material and psychological traces,” says the gallery director Aleya Hamza. “Through El Meleegy’s reassemblies of Fathy Mahmoud’s industrial porcelain fragments and Marianne Fahmy’s hand-embroidered visions of a relocated Alexandrian population, imagining the submersion of the city, our presentation links the city’s histories of labor, nationalism, and environmental precariousness to broader global patterns of production and displacement.”

Land, and its connection to process and the body, lingers at Tunisian gallery Selma Feriani’s booth, with a grouping of artists including Filwa Nazer, Fares Thabet and Maha Malluh. Nazer’s topographic mixed-media diptych, Brutalism (2025), has equally dreamscape and militaristic feels, with a bird’s-eye view of an abstracted territory of tulle, silk and cotton – tranquil and alarming at the same time. In Thabet’s painting Grandfather’s Caravan (2025), landscape is both an impossible destination and a politicised terrain: erect lush palms reach towards the azure sky, while luxuriant grass extends merrily to the sea and a rocky beach. The calmness, similarly to Nazer’s rhythmic geometry, hints at the precariousness of all things serene, prompting the viewer to follow each brushstroke with caution.

Alarm bells also ring in Omar Fakhoury’s solo booth at Beirut’s Marfa’ Projects, albeit echoing back to the days of childhood’s peculiar unknowns. The paintings and sculptures from his Touch Wood series, which he debuted at the gallery last year, meander through an uncanny forest of superstitions and myths. Passed down through generations, these mind-bending beliefs particularly haunt childhood, a time when the border between reality and the imagined is at its thinnest. Paintings such as Leave scissors open, and people will speak badly about you or When you hear an owl hoot, flip your shoe 3 (both 2025) illustrate their titular superstitions with a cartoonish breeze, reminiscent of children’s book illustrations (as well as early twentieth-century Modernism) and a reminder of the enduring – and often competing – threads of perceived and real memory in today’s art.