With a background in fashion and a passion for textiles, the artist weaves an artful path through issues of the body and personal identity.

Filwa Nazer’s creative career did not begin quite as she had planned. After her application to art college was rejected, the young Nazer followed a friend to Milan’s reputed fashion and design school, the Istituto Marangoni – a move that would foster and shape her eventual journey into the art world. What might have initially seemed like a setback was, in the longer term, a formative period for the Saudi artist, who went on to study art in Jeddah and London and has become well known for the innovative use of textiles in her work. It was only when she was in the midst of moving her life back to Saudi Arabia from London that the penny dropped for Nazer. “The realisation that my background in fashion could be an important tool in my artistic process came about when I was going through [this] personal transition in my life,” she tells Canvas.

It was also during this moment of change that Nazer began to explore a theme that would become prevalent in her practice. “I was looking into ideas of embodiment and started thinking about how I can inhabit my body – how the body in itself is a container of our energies, emotions and memories, and how it relates to the spaces in which it finds itself,” she says, reflecting on how a period of “digging deeper” into this topic brought her right back to her fashion school days. “All these ideas led me to use the medium of textiles,” she explains, “because garments and clothing are like an extension of the skin of the body.”

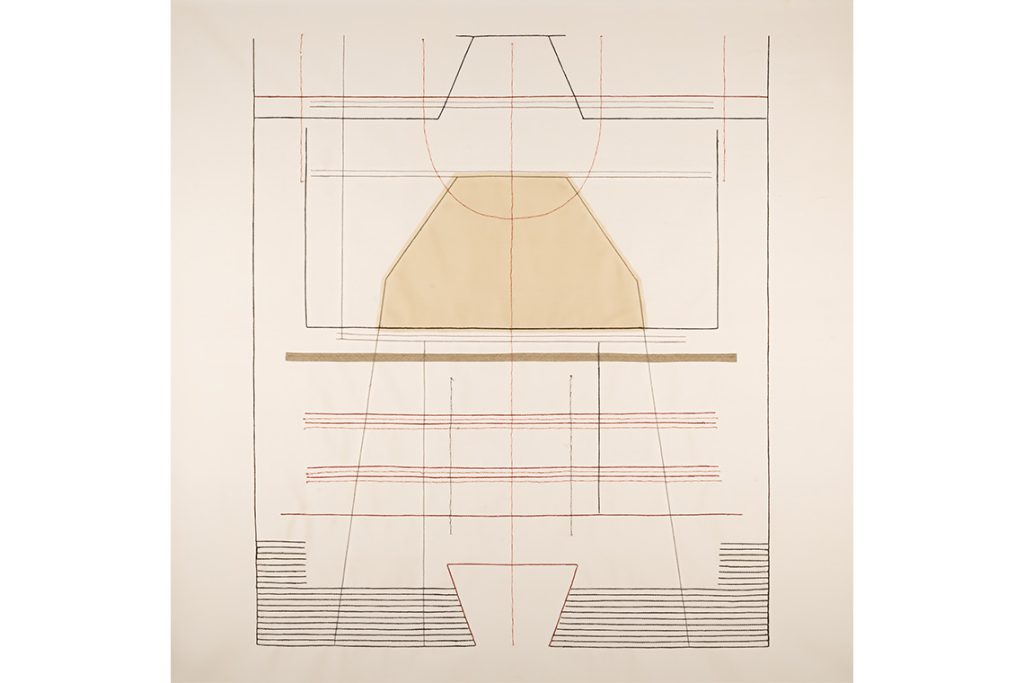

Commissioned by Sharjah Art Foundation. Image courtesy of Saudi Ministry of Culture collection, Riyadh and the artist

Thinking about the relationship between the body and the various spaces it inhabits, Nazer began to draw links between fashion and architecture. “I started making connections between the tools of garment construction, like pattern-making techniques, and architectural tools such as floor and house plans,” she continues. Her exploration of these connections found fulfilment in Nazer’s first large-scale textile installations, the series Sites Unknown, exhibited at Jeddah’s Hafez Gallery in 2019. Among the works shown were The Skin I Live In and Missing A Rib: the first a two-metre-high structure of layered muslin and polyethylene, reminiscent of a skirt, the embroidered muslin cut according to the floorplans of Nazer’s London flat; and the second – drawing this time on her house in Jeddah – comprising a transparent, embroidered outer layer cloaking an internal structure of white strips, resembling a broken rib cage. Both in its allusion to the story of Eve being created from Adam’s rib and the application of a decorative technique used in men’s undergarments in Saudi Arabia to construct the interior “rib cage”, Missing A Rib speaks to the theme of masculine control in a woman’s private space – in this case, the artist’s own home.

A particular focus on female identity, the embodiment of space and participation in public life has emerged as a common thread that links Nazer’s later works to these first textile installations. It is perhaps best exemplified by her Five Women series, commissioned for the first edition of the Diriyah Contemporary Art Biennale in 2021. “Each installation in Five Women holds the story of one Saudi woman of my generation and a particular incident that defined her relationship with her body,” says Nazer, explaining how, in decades past, women of her generation “had much more limited engagement with public space” than today. In the face of such limited interaction with the world at large, it was in the private domain that women were able to assert their identity. “The installation N.T, for example, part of Five Women, reflects on how Saudi women at that time used fashion flamboyantly in private spaces, mostly amongst their peers,” she notes. “[Fashion was] an important outlet for self-expression… asserting the woman’s status and character.”

As Nazer’s installations examine embodiment and transition between private and public spaces, so her works themselves are often remarkably site-responsive. “My works in textile often respond to a particular space or a building, in relation to my body or women embodying particular spaces,” she shares. Her series Tactile Mapping (2019), for instance, takes as its subject the daily life of the inhabitants of Beit Al Hurma, one of the traditional coral-stone houses that form part of the UAE’s Sharjah Art Foundation and in which the works were displayed.

Image courtesy of the Royal Commission for AlUla

This characteristic site-responsiveness is not exclusive to Nazer’s work with textiles. It was taken – quite literally – to new lengths in 2024, when Nazer created her elevated walkway, Preserving Shadows, at Desert X AlUla. Reflecting on the sands and rock formations of the desert valley of Wadi AlFann, Nazer speaks of the “challenge of creating a work that cannot only survive the logistics of the desert but also conceptually engage with this sublime environment in an impactful way”. Although she initially struggled to connect deeply with the landscape – monumental in its scale and challenging to grasp fully – Nazer instrumentalised her “discomfort and fear”, using it as a catalyst to “research the history of fear of the supernatural in this particular part of the Kingdom”. The undulating ramp – made of black steel mesh – takes the form of “an abstract skeleton of a snake”, actively encouraging visitors to engage with the mysteries of the desert.

“As we ascend the ramp we are faced with big, shadowy black mesh triangles on both sides,” the artist explains. These triangles become smaller the further the visitor progresses along the ramp, eventually “subsiding completely” when they reach the end. It is there, on the balcony, that “we are faced with the vastness of the desert”. Stretching for 40 metres, the architectural installation requires the sandy-shoed visitor to make their own journey through and beyond the shadows. “I wanted to create a work that we engage with physically and attempt to experience as a vulnerable journey of overcoming fear,” Nazer says.

Journeying, through the shadows of the desert or in the sometimes discomforting transition between socio-cultural spaces, has been fundamental to the evolution of Nazer’s practice. Nonetheless, the artist – who was born in Wales but grew up in Saudi Arabia, received her creative education between Europe and the Kingdom, and has been represented by Tunis- and London-based Selma Feriani Gallery since 2023 – maintains that her “Saudi/Hijazi identity is always present” in her works. Whether employing fabrics or metal, and even if it is “filtered through [her] other experiences and education abroad,” this identity is ever “the seed that instigates”. With Paris+ par Art Basel 2024 on the horizon and a solo show with Selma Feriani Gallery in the works for 2025, one thing is clear: that seed is continuing to bear fruit.