A unique spirit of creativity encompassing everything from material culture to contemporary art has characterised the desert city of AlUla since the days of its ancient civilisations.

Standing 50 metres above the ruins of Dadan, the capital of the ancient Dadanite and Lihyanite kingdoms that once ruled the AlUla Valley, two pairs of formidable lion reliefs guard the tombs carved into the face of a red sandstone cliff. Teeth bared as if to ward off looters or evil spirits, these funerary monuments were likely constructed to mark the burial of elites living under the Lihyanites, who settled in the area between the fifth and first centuries BCE. Also cut into the cliff face – a considerable feat without the use of modern construction equipment – the lions are evidence of a rich and advanced culture of craftsmanship that flourished in Dadan thousands of years ago.

The statues are among myriad handicrafts and other elements of material culture – including cultic objects such as incense burners, textiles, jewellery, sculptures of kings, inscriptions and petroglyphs – that have been unearthed as part of a series of archaeological excavations around Dadan, most recently by the Royal Commission for AlUla (RCU) in partnership with the French Agency for AlUla Development (Afalula). Many of the finds will be housed in the projected Museum of the Incense Road (MOIR), which was announced by the RCU last May and will explore the eponymous trade route that connected northwest Arabia with neighbouring civilisations in southern Arabia, Egypt, Mesopotamia, Greece and Rome. Drawing on the material culture of AlUla and its major sites, including Dadan, Hegra and Tayma, the museum will place the oasis city at the heart of the Incense Road’s history as a nexus of civilisation and trade.

Evidence of the exchange of craft traditions between geographies can be found in the material culture of the period, but the Incense Road trade, which began at least 2500 years ago, marks the origin of a creative spirit at AlUla that has also endured across time. The lion reliefs, for example, were crafted by merchants from the city of Ma’in in modern-day Yemen, and who set up a trading colony in Dadan. Trade from southern Arabia was an early and major strand of the network that would eventually lead to AlUla’s reputation as a meeting point of cultures.

Dadan was a vital transit point for merchant caravans transporting goods – particularly frankincense, at the time harvested primarily in southern Arabia – to markets in Egypt, the Mediterranean and Mesopotamia. “There was an extremely high demand for incense and a very limited supply,” says Jérôme Rohmer, a researcher with the French National Centre for Scientific Research, which is leading the project in Dadan on behalf of the RCU and Afalula. “That made it the most valuable commodity in antiquity, comparable to oil in modern times.”

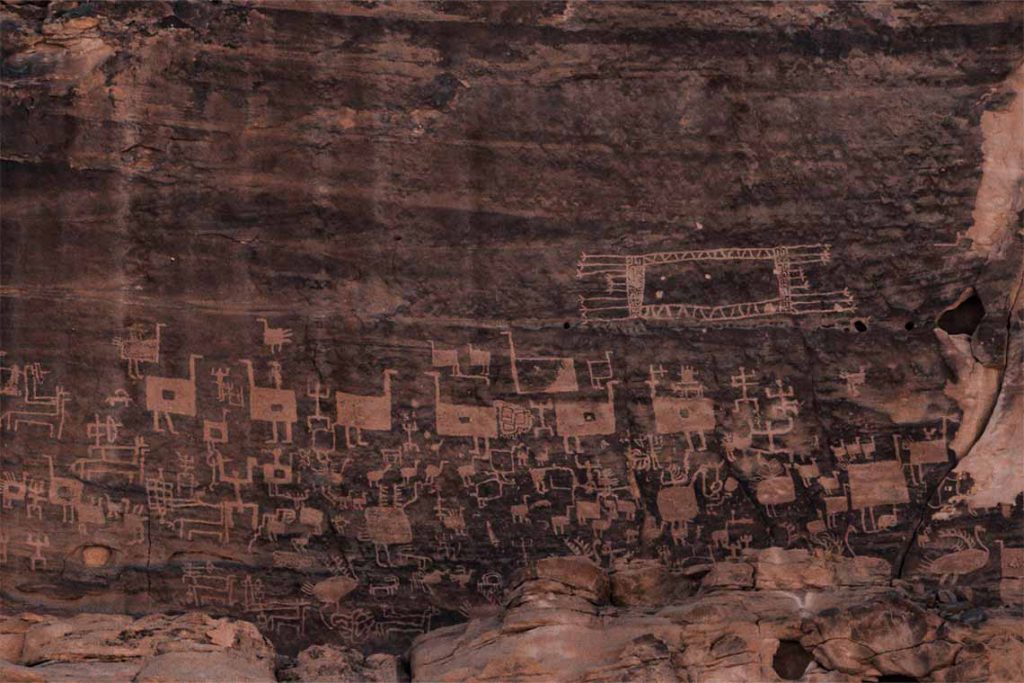

The presence of the southern Arabian trading colony is evidenced by inscriptions seen on the lion tombs, and which are among thousands of other inscriptions as well as petroglyphs found at various sites around Dadan. Less than ten kilometres from the city ruins in Jabal Ikmah – listed on UNESCO’s Memory of the World Register last year – the mountainsides are carved with layer upon layer of messages describing the daily lives of consecutive civilisations. These are mostly in the ancient Dadanite alphabet, but also appear in Arabic, Thamudic, Minaic and Nabataean scripts and span from 2500 years ago to the third century BCE. Some are likely to be the work of master craftspeople from Dadan whom were commissioned by wealthy individuals to keep records, while other carvings are illustrations depicting agriculture, animals, pottery and musical instruments. These are also found in abundance at Wadi Alnaam, famous for its petroglyphs of ostriches and which opened to the public in November. Further afield in Hegra, which celebrated 15 years as a UNESCO World Heritage site in 2023, the architecture of the Nabatean tombs provides more evidence of the confluence of cultures in AlUla, showing influences from Mesopotamian, Greek and Roman and Egyptian traditions.

Many of the inscriptions around Jabal Ikmah and Wadi Alnaam were made by present-day picnickers or wandering locals from AlUla in far more recent years, symbolising the continuity of material culture in the city across generations. A more concrete manifestation of this sense of continuity lies in the area’s building traditions, since the same materials and methods of construction are available to its current inhabitants as to their ancient predecessors. “For instance, if palm tree fronds are used to construct a roof, then the rooms cannot be wider than five metres – the average width of the fronds,” explains Rohmer. Over in AlUla’s Old Town, meanwhile, Madrasat Addeera in the AlJadidah Arts District teaches local women and the general public skills in traditional handicrafts, including stone carving, based on historical craft objects.

This inheritance of creativity from the ancient kingdoms is not limited to local material culture, however. The RCU recently announced plans to open two educational visitor centres at Dadan and Jabal Ikmah to be designed by Clément Vergely. In the French architect’s vision for the buildings, the design will respond to the surrounding context, engaging with not only the locally available materials but also the intangible heritage of AlUla, such as the Nabateans’ practice of reusing stone blocks removed from the tombs at Hegra for the construction of houses, streets and wells. “An important question for us is, how can we create a building today that will become part of the heritage tomorrow?” Vergely says.

Speaking to Canvas, Dr Helen McGauran, heritage curatorial expert with the RCU and curatorial lead for MOIR, echoes this line of thought. “There is a sense of continuing creativity that is visible not only in the material culture, but the scale of ambition in AlUla,” she says. “From the monumental tombs of Hegra to the monumental project at Wadi AlFann, we’re continually adding new layers to the story of AlUla by looking back at the past and reinventing it for the 21st century.”

An expansive contemporary art venue set in the AlUla desert, Wadi AlFann – or ‘Valley of the Arts’ – is scheduled to launch its first open-air exhibition of artist commissions this year. In 2022, Iwona Blazwick, former director of London’s Whitechapel Gallery, was appointed chair of the RCU’s public art expert panel to oversee the commissions. To be realised by five artists – Ahmed Mater, Manal AlDowayan, James Turrell, Agnes Denes and Michael Heizer – the huge site-specific installations will speak clearly to not only the surrounding environment but also to local craft traditions.

AlDowayan, the Saudi Arabian representative at this year’s Venice Biennale, will present Oasis of Stories, an immersive architectonic sculpture that evokes AlUla’s labyrinthine ancient settlements and which will be permanently installed at Wadi AlFann from 2026. In the lead-up to the unveiling, the artist will showcase two exhibitions charting her journey to realise the work at AlJadidah Arts District as part of this year’s AlUla Arts Festival. For one of these, in an extension of the historic inscriptions and petroglyphs that abound across Jabal Ikmah, Wadi Alnaam and other sites, AlDowayan conducted a series of workshops inviting around 1000 participants – including artists, craftspeople, students and a disability association – to contribute their personal stories to the sculpture’s walls.

Heizer’s work, similarly, will consist of engravings carved into the area’s sandstone topography. In the same vein as Madrasat Addeera and Vergely’s planned visitor centres, the works at Wadi AlFann represent a tradition of what Dr McGauran calls “monumental mark-making” and which has fired the successive chapters of AlUla’s history for more than two millennia.

This feature first appeared in Canvas 111: Crafting the Contemporary