The latest iteration of the Lyon Biennale takes water as its creative premise and specifically the confluence of rivers and what that might signify for wider awareness of who and what we are.

Even by the standards of such events, the 17th Lyon Biennale – Les voix des fleuves, Crossing the Water – is a strange proposition. Its peculiarity comes not from the character of the work on display, nor from the places in which it is shown: it is strange because, in contrast to the defining dogma governing twenty-first-century biennales, its organising principle is so vague as to be almost invisible. The idea, insofar as there is one, is that participating artists consider the confluence of rivers at the heart of the host city and somehow respond with work that converses with the image, whether literally or figuratively. You could, if so willed, read anything into the metaphor of two bodies of water meeting – and if the work here is anything to go on, its creators have done precisely that.

The lack of curatorial ego does nothing to stand in the way of stupendous results. The event’s central exhibition is a vast affair taking over the entirety of two warehouses only recently vacated by the SNCF, the French national railway company, packing them with monumental, attention-grabbing installations of the sort largely eschewed by intellectually self-conscious biennale coordinators over the past decade. The general mood is mischievous, with a soft-touch but broadly intelligent approach to serious matters. Even the vending machines, provided by Austrian collective Healthy Boy Band feat. Public Possession, are in on it, offering healthy snacks in Keith Haring-lite packaging.

Photography by Jair Lanes. Image courtesy of the artists

A film by Jérémie Danon and Kiddy Smile, entitled RIDE (2024), sees French citizens of African or Caribbean descent ride through a city at night discussing the particularities of being black in present-day France, pulling no punches when it comes to discussing, for instance, tokenism in the country’s cinematic tradition. They speak of “the white gaze” – I sat up at that – and, in some cases, the sense of being made to feel like second-class citizens – “French, but not quite”, as one subject puts it. It’s a cinematic achievement in itself, shots switching perspectives constantly, cut to the rhythm of a suspense thriller.

Elsewhere, in a walled-off office, its windows covered with yellow plexiglass, Julien Discrit presents Forever Reverb (2024), a bizarre installation investigating the sensory experience of people experiencing age-related memory loss and trauma. It features an eerie video that trawls through nostalgic, Wes Anderson-inflected interiors to an AI-generated soundtrack of what sound like lost Roy Orbison classics: Discrit imagines a choose-your-own-memory future – a kind of pension-age remake of Total Recall. But does anyone really want to be that selective?

The philosophical quandary sticks in the head as you traipse across the hall to a presentation by the reliably excellent Majd Abdel Hamid, who confronts us with Texture of Memory (2024) consisting of a selection of delicate little embroideries on paper, gauze and other found materials, this time created with specificity to Lyon itself. Once a major centre for Europe’s silk industry, the city is a natural partner for Hamid’s work, which in this instance riffs on the Jacquard loom, a radical development pioneered in eighteenth-century Lyon that made possible large-scale production of sophisticated patterns. The results of this meditative but deeply personal process are as exquisite as anything the artist has made, and a highlight of the wider biennale.

The good news continues through the Institut d’art contemporain, where emerging artists have been given the budget to splurge on some highly impressive installations. Be Our Guest (2024) is a conversational, engaging room by American artist Hilary Galbreaith explores the internal contradictions of the tourist economy, styling her space as a sort of archetypal Airbnb let with a massive, bright orange flowchart filling the walls and testimonies she has collected from workers in the sector printed onto the futons spread out across the floor. Not everything hits the spot, however. A showcase at the Cité internationale de la Gastronomie, for instance, is directionless rather than free-form, while an enormous exhibition at MAC Lyon – always a tricky venue to fill – is decidedly uneven.

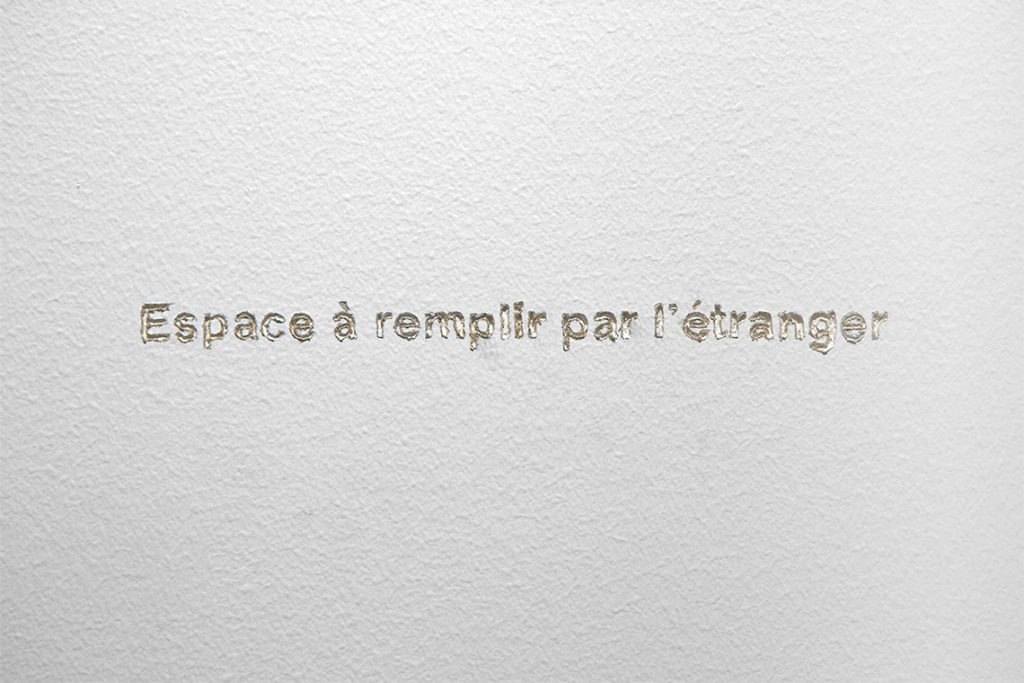

Still, there are highlights, many coming from the disappointingly slim selection of artists from the MENA countries. Morocco’s Latifa Echakhch’s work Hospitalité (2006) probes the cultural ostracism many migrants from North Africa face on arrival in Francophone Europe with a shallow engraving bearing the words Espace à remplir par l’étranger (Space to be filled in by foreigner), a routine phrase printed on the residency permits issued by police prefectures. More notable entirely is a series of installations by the Palestinian conceptual artist Taysir Batniji, of which Au cas où #2 (2024) is the most effective and indeed the most harrowing. It consists of several dozen photographs of house keys held by refugees forced into camps since the start of the ongoing war on Gaza. That the large majority of these keys may be all that remains of the homes they once unlocked is a thought as startling as it is tragic.

It’s odd to encounter such a charged, devastating piece amidst the context-free clamour of unrelated installations here – to deploy the only simile that comes easily to mind, it’s a little like the shock of coming across an Instagram post relating the specifics of a war atrocity amidst a feed otherwise full of wilfully inane memes. This is the world we live in; the message seems to be – and even in the context of a largely celebratory art biennale, it can still sneak up and punch you in the gut.