In its latest iteration, the contemporary art festival Survival Kit has evolved from conceptual provocation to urgent necessity. It seeks to provide a toolkit for navigating geopolitical upheaval through mythological birds and horizontal networks.

In a former knitting factory in Riga, the sixteenth edition of Survival Kit unfolds as an urgent meditation on vision, survival and the collapse of imposed narratives. Curated by Slavs and Tatars alongside Michał Grzegorzek, House of See-More takes the mythical Simurgh – a genderless, flame-wreathed bird from Eurasian folklore – as its guiding spirit through territories both geographical and metaphorical and which resist easy categorisation.

The exhibition’s title has gained fresh urgency in recent years. As LCCA founder Solvita Krese reflects: “The last three years since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, we shifted our focus of activities very much toward Central Asia and Caucasus… building this horizontal network somehow to facilitate the process of decolonisation.” The curatorial statement is uncompromising: “As the world around us burns, the first sparks come from the brittle words and parched terms we use to define ourselves.”

The curatorial vision extends beyond the familiar post-Soviet framework, reaching toward what the curatorial team term “horizontal bridges of cooperation” – direct connections between regions that bypass ideological centres like Moscow or Western Europe. This approach seeks to connect Central Asia, the Caucasus and Eastern Europe through shared experiences and mythologies, rather than imposed political frameworks. The Simurgh becomes a vehicle for reimagining – a creature that has “witnessed the destruction of the world three times over” and embodies multiplicity rather than singular identity.

Image courtesy of the Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art

Walking through the space, one encounters this philosophy made manifest in works that resist containment within neat categories. Roman Khimei and Yarema Malashchuk’s You Shouldn’t Have to See This (2024) confronts viewers with the sleeping forms of Ukrainian children who were forcibly taken to Russian territory and later returned. The video installation’s silence amplifies the work’s terrible weight – these images should not exist, the artists remind us, yet their documentation becomes crucial testimony. The screens, positioned at varying heights from floor to eye level, create different viewing relationships; a child visitor kneels before the knee-height monitor, unconsciously mirroring the vulnerability on screen. These static videos, with minimal movement within each frame, stretch duration into an almost voyeuristic endurance test, forcing prolonged confrontation with scenes that demand witness yet resist comfortable consumption. As Malashchuk explains: “It speaks about this time, the time that we can’t really achieve when we are scrolling the news… it’s a motion image, but it’s still time-based… you can stay around this reality for a bit.” As the artist explains, the title itself acknowledges the ethical complexity: “These images shouldn’t be ever created, I think… but in this particular reality Ukraine is going through, I think this is rather relevant.”

Syrian-German artist Enad Marouf’s Time of the Angel (2022) offers a different register of remembrance. The performance, captured on video, presents an angel as a figure that “unsettles preconceived notions and norms” through processes of memory and loss. Marouf’s choreography weaves ballet sequences with intimate gestures, creating a temporal space where absence and presence blur. The angel, he tells Canvas, “embodies the capacity for thought and reflection, particularly in moments of uncertainty shaped by fear.” Drawing on Walter Benjamin’s “angel of history” – which looks back at catastrophe while being pushed forward by progress – he suggests that “the Simurgh and the Angel share together this ethical stance” of bearing witness to historical ruins, rather than forgetting them.

An olfactory assault greets visitors descending into the lower galleries, where Malina Suliman’s Afghan Women Wishes (2025) spreads across three large fabric panels. The newly commissioned work employs curcuma, cumin and chilli as both material and metaphor, their fragility mirroring the precarious nature of aspiration under oppression. Since the Taliban’s return to power in 2021, Afghan women have faced systematic erasure from public life, and Suliman’s handwritten wishes become acts of resistance – personal desires that refuse to be silenced, despite institutional violence.

Askhat Akhmedyarov’s “Қaйдa?” (“Where?”) (2025) documents the artist’s flag-bearing journey across Kazakhstan’s landscapes, questioning the direction of a nation still navigating post-Soviet realities. The work’s placement on the exhibition’s stairway – a transitional space between levels – underscores its interrogation of directionality and national purpose. Akhmedyarov’s superhero-like cape against the stark Kazakhstani terrain creates a visual language that oscillates between the heroic and the absurd.

Image courtesy of the Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art

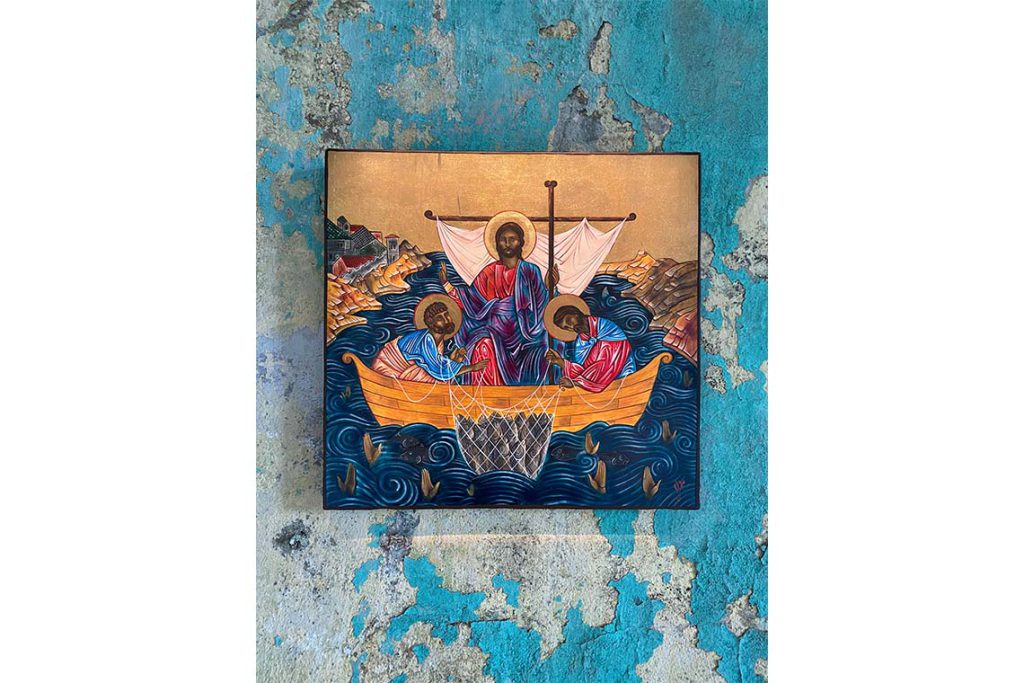

If Akhmedyarov probes questions of national identity through movement and gesture, Oksana Shachko turned to the stillness of iconography to mount her own insurgent critique. Her subversive icons from 2016 demonstrate how traditional forms can be weaponised against orthodoxy itself. Trained in classical Orthodox icon painting, the FEMEN co-founder’s Iconoclast series appears conventional at first glance before revealing transgressive details – female crucifixion figures, gambling angels, dinosaurs replacing dragons. These works function as theological interventions, challenging both religious doctrine and patriarchal authority through technical mastery turned toward radical ends.

Where Shachko repurposed sacred aesthetics, Shadi Habib Allah works with the overlooked and discarded. His In Stock (2018) transforms shrink wrap – normally used to preserve and protect – into brittle sculptures that speak to economic precarity and the informal economies of survival. Referencing the corner stores of Florida’s former food deserts, these ghostly forms suggest both absence and accumulation. As the artist explains, they represent “empty merchandise that was never sold” – goods reported as transactions, but which were in reality part of an alternative economic logic. Co-curator Payam Sharifi from Slavs and Tatars notes: “It’s not easy to make works that are so loaded with political content that are not in any way wearing it on their sleeves… they contain their vessels of so much meaning.”

This quiet intensity also surfaces in Ali Cherri’s The Watchman (2023), which perhaps most directly confronts the exhibition’s broader critique of imperial power structures. Set on the militarised border in Cyprus, the film renders the soldier – typically a symbol of state authority – as fundamentally impotent. The Turkish soldier in his watchtower becomes a figure of waiting rather than watching, haunted not by conflict but by futility. Cherri’s camera lingers on reflections that obscure vision, on sweat and uncertainty, transforming the border guard into a meditation on the emptiness at the heart of territorial control.

Throughout the exhibition, works create unexpected dialogues across cultural and temporal boundaries. Luīze Nežberte’s towering trash bins – sheet metal painted in black and white to mimic Greek architectural proportions – frame the Ukrainian children’s videos, their classical columns constructed from the most mundane of objects. These pragmatic-symbolic hybrids create sight lines that implicate viewers in the act of witnessing. The sensory intensity – turmeric’s earthiness, the tactile quality of Suliman’s spice-painted surfaces – demands bodily engagement with political realities often kept at comfortable aesthetic distance.

Image courtesy of the Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art

The curatorial gambit of introducing the Simurgh into an Eastern European context proves generative precisely because it refuses cultural purity. As Jacob Mikanowski’s research, quoted in the curatorial statement, argues, Eastern Europe has never existed without Islam: the “silver thread” holding diverse traditions together. Yet this hybridity has been repeatedly disavowed in favour of nationalist myths of cultural homogeneity. Notably, while the curatorial framework foregrounds Islamic cultural traditions, few of the exhibited works directly engage with this heritage – a gap that perhaps reflects the complex realities of cultural translation across borders.

The exhibition’s strength lies in its refusal to provide easy answers or comfortable resolutions. There’s perhaps something idealistic in the curators’ suggestion that regional affinities organised around harvest festivals, trade routes and culinary traditions can cleanly escape the hierarchical power structures that have historically shaped them. Yet the works themselves resist such tidy optimism. Instead, they offer what the curators call “flamboyance as a means of liberation” – a burning bright enough to match the conflagration consuming established orders. In a world where identity is increasingly weaponised as singular and reductive, these artists insist on multiplicity, on the productive uncertainty of dwelling at borders rather than centres.

House of See-More suggests that survival itself requires this kind of promiscuous border-crossing, this refusal of fixed identity. The Wonderbird of Latvian folklore that opens the exhibition’s curatorial statement brings sight to a blind king through kindness and cleverness, perhaps pointing toward the empathetic vision needed to navigate our current geopolitical moment. Whether such a vision can sustain itself beyond the gallery walls is a different question, but in this refurbished factory space, the Simurgh spreads its wings over a compelling argument for horizontal solidarity in a world still too often organised by vertical power.