The artist’s photography blends everyday scenarios with the fantastical and absurd, often featuring students or children to reflect surreal moments in contemporary Moroccan society.

Hicham Benohoud’s photography is a fascinating proposition, a striking and often lyrical blend of the quotidian and the poetic, flavoured throughout with a welcome dose of absurdity. It is, moreover, profoundly marked by the particularities of his native Morocco. A typical series might see street donkeys roaming freely around the plush interior of a holiday villa, or groups of children performing precision-choreographed acrobatic stunts within minuscule lodgings. His work could be compared to the literary mode of magic realism, in that it employs strange, borderline fantastical imagery to hold up a mirror to society. Present-day Morocco, in Benohoud’s words, is “a bizarre, surreal place – hypocritical, improbable. But I don’t make art about political causes. I make work about myself, as a Moroccan who sees that his own society doesn’t fully function.”

When we speak via videocall, Benohoud is in his home studio in Marrakech, the city in which he was born in 1968. He was always intrigued by the arts as a youth, but did not have much of a frame of reference. “The truth is that I started out as an artist without knowing much about art,” he recalls. “I didn’t go to art school. I did an art baccalaureate, but it was very technical – drawing lessons, lessons in perspective, in painting… really just the basics.” Nor was there anything resembling a contemporary gallery scene. “There wasn’t really a way of learning about what was going on currently, nor any focus on how you might develop as an artist – no advice as to how you might approach a personal project, for example.”

So it was that Benohoud decided to teach art himself. After two years in teacher training college, he was thrown into the dysfunctional world of the Moroccan education system – an experience that would set him on his path towards becoming an artist. “Every lesson I gave would last for exactly an hour and was always the same, so I tried to break the monotony by photographing my students. I didn’t have a particular idea at first […] and I didn’t even know that photography was an art form in its own right!” It was, he says, “completely by accident” that he alighted on the medium as his primary means of expression. “I realised that I couldn’t actually draw very well,” he admits. “I could obviously do it – I was an art teacher! – but at the time, for me, the point of drawing was to create something as accurate as a photograph, and I wanted to make a series of really hyper-realist images. So, I bought myself a camera to photograph my students and use this as a basis for drawings.”

The process led him to realise that these reference pictures could be an end in themselves. His first efforts involved taking thousands of passport-style photographs of his students. “I laminated them, cut out the defining facial features – such as the mouth or the eyes – then went over these pictures with various pigments and the like. I took the measurements of the Moroccan ID card at the time, which were 5cm x 7cm, and then absolutely covered the walls with these images, these little ID cards. That was really my first exhibition.”

What followed was a series entitled La Salle de Classe (1994–2002), a dream-like and often joyful celebration of youth that also served as a critique of institutional education and its myriad failures. Shot in black and white, its constituent images see Benohoud’s pupils rejoicing in the comparative freedom of his art classes, clearly enjoying the strange mise-en-scènes and props that their teacher was creating from basic art class materials. One sees a boy seemingly floating above the desks of his classmates, his body almost entirely enveloped by a pyramid-shaped white tarp; another (which the artist himself has elsewhere identified as his “best shot”) depicts a particularly cheerful child with his legs submerged in cardboard tubes, others covering his arms and – the suggestion is – chaining him to a force far out of shot.

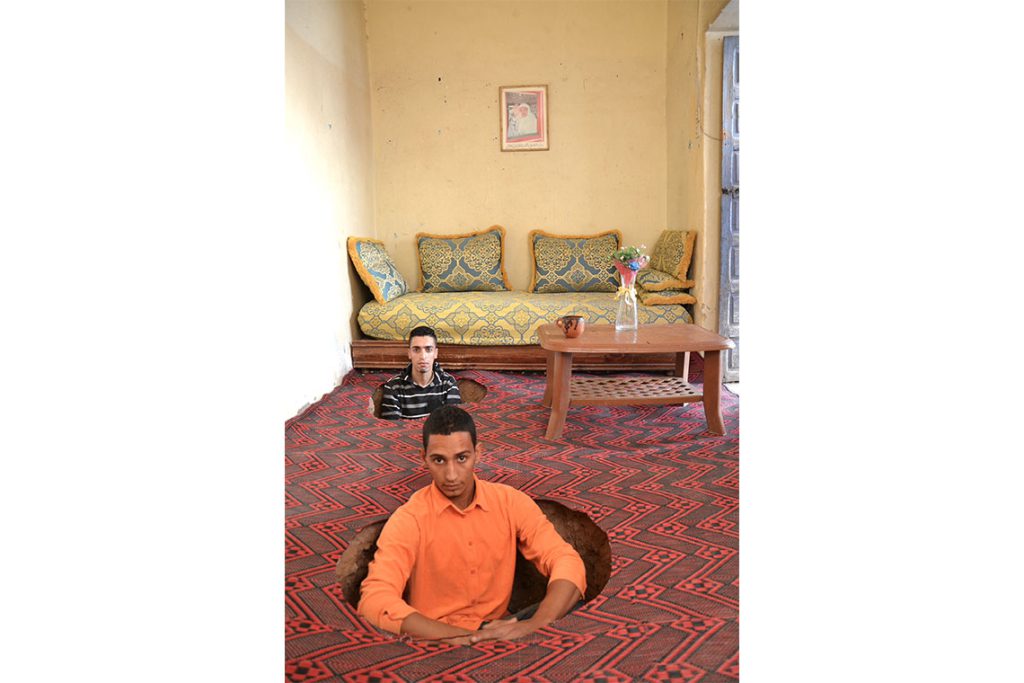

In 1998 Benohoud was invited to exhibit the series at the French Cultural Institute in Marrakech, an experience which would prove pivotal to his career, leading to invitations to exhibit in France, to where he subsequently moved. After seven years (“too long”), he returned to his home country and could not contain his surprise at what he found. “When I was living in Morocco before, there was a lot of poverty,” he explains. “But it was a country that was developing, thanks to globalisation. There was a rural exodus to the cities, there was the internet, there was what one could call ‘progress’.” When he returned, he expected to see more evidence of that ‘progress’. “Instead, I found that nothing had changed at all. I started to see Moroccans as trapped in a hole, trying to escape.”

The visual image that came to Benohoud was of a people stuck fast in a pothole, attempting to squeeze themselves out but constrained by their circumstances. Translating this vision into the series which became The Hole (2015) was a labour of love: first off, Benohoud had to find models willing to pose for the pictures in their own homes; second, because he prefers to work without digital tweaking, he had to persuade them to let him create actual holes therein, into which they had to squeeze themselves to give visual form to his idea. “I felt a bit like a film director,” he explains. “Creating a world one day, rebuilding it to its previous appearance the next.”

The Hole is one of many pieces Benohoud has produced on the bizarre realities of his home country, a condition he expresses via his absurdist approach. “There are two completely contradictory worlds coexisting side by side in Morocco. As in every society, there’s rich and poor, but here, there’s a particular hypocrisy to it.” As an example, he cites Ânes Situ (2012–13), the series he made with the street donkeys. “I realised that in the same Casablanca street, you could see super-deluxe cars like Bentleys sharing the same road as donkeys.” The latter, Benohoud says, are considered “dirty animals – a form of transport which allows people to survive […] I didn’t want to photograph donkeys in their natural environment. I wanted to put them in a different context entirely, as a metaphor for Morocco’s contradictions.”

While post-colonial thought has become a mainstream cultural theme over the past decade, even in Europe, Benohoud considers it irrelevant to his practice. “What influences me is my own personal identity, how it is to be born into this society,” he explains. “In Morocco, the individual does not exist – you can’t be different. So it’s been important for me since birth to affirm my individuality. The whole notion of personality revolves around being different. But I know that there are limits you have to stick to, because if you don’t, you’ll be in trouble. So I try to create a personal world.”

In so doing, Benohoud has managed to become a major force in Moroccan art. Yet, he says, he has no particular plans in the offing. “I’m not currently working on anything that’s really captured my interest,” he admits. I suggest to him whether, given the elaborate set designs he conceives for his photography, it might not be the moment to begin experimenting with video, a medium to which his aesthetic would lend itself perfectly. “I’d love to,” he responds, “if I had the means to do so. It’s a very technical process… and I’m not a great technician.” Nevertheless, Benohoud says, “an idea will come to me. It may not be clear now, but the right moment will arrive.”