In an intimate setting, the three-artist exhibition at Palo Gallery in New York weaves together personal and collective impressions on the Palestinian experience.

The lens is a good friend. A loyal chronicler of the fickle memory, the camera captures and holds the moment with a diligent firmness. Unlike the visual slipperiness of paint or of clay, photography echoes the instant with its disarming reality – a beautiful trait that is brutally raw and even painful at times. A place or a person forever inhabits the frame against the unforgiving gush of time.

The documentarian power of photography helps many displaced artists ease the longing for the home left behind. The camera not only envelops an impression through the aperture but the fleeting moment also seeps through the consciousness of the beholder, filtered through the burden and joy of the bygone moments. Palo Gallery’s current show Longing: In Between Homelands features photographic work by three artists with Palestinian roots: Lina Khalid, Ameen Abo Kaseem and Nadia Bseiso. The images on view at the New York gallery’s East Village space meander between documenting and monumentalising, revelling in their mundanity at a time when normalcy is a distant oasis. Children joyfully play inside a pool, an old man woefully strolls by the beach, and a group of young people protest on the streets. Tension and tenacity traverse places familiar for their photographers, with a step of alienation. The artists’ presence remains both vehement and spectral, while their subjects face the new day.

In Bseiso’s Hot Spring (2017), four children play in a lush marsh at a border town in Jordan. Unfettered by worry, they have plunged into the placid water with their clothes on, perhaps escaping the harsh heat. The image belongs to a series in which the artist explores the current agricultural state of the region known as the Fertile Crescent, where the Arabian Gulf today meets Syria, Iraq, Jordan, Israel and Palestine. The land gloriously claims the picture frame in Road to Wadi Araba (2016), in which two men greet each other by a solitary tree in the desert. The tree’s insistence on thriving in the arid soil defies the contextual odds, like the joyful encounter of the two human figures in the contested yet seemingly manless place.

Image courtesy of the artist

The earth rather claims the centre stage in Khalid’s black-and-white images of textured soils and winding roads. In them, soaring mountains blend with the endless sky, or the Dead Sea hits a barren shore. Lonely Beach (2024) does justice to its evocative title. Apart from a dilapidated shack, the curved shoreline is left to the calm sea and the sharp sun The uninhabited stillness, however, is interrupted by a figure walking across the rocks towards the far-right side of the image. The Sea Is Over There. Do You See It? (2024) underlines its questioning title with the absence of any mass of water. Instead, a section of barbed-wire fencing slices through the lush vegetation covering the ground, from where plants spike towards the sky. The still monumentalises the impossibility of crossing such a boundary to reach the sea, while still offering comfort in the knowledge of the latter’s distant presence.

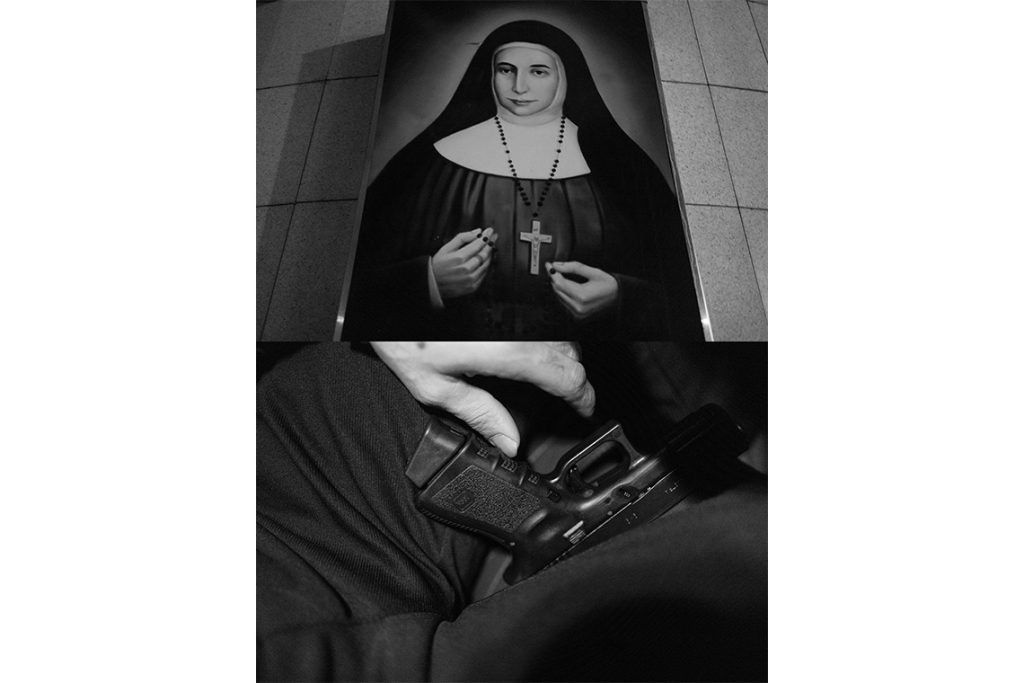

Kaseem’s untitled images occupy a line between calmness and discomfort. Among the works that unite two cropped images is a pairing of a boy with his face turned up towards the sunny sky, his eyes shut, with a view of the back of two soldiers seemingly marching along a pavement. Another juxtaposition shows a young woman kissing her lover, matched with a group of street protestors draped in keffiyeh. In each combination, an account of shared reality blends with the subjectivity of truths as internalised instances of existence. Text accompanying the images heightens their immediacy. “What are you scared from? Death?” reads a stencil on the gallery wall next to the top of an image of a child holding a bunch of flowers. He appears to have left some of the blooms in a makeshift plastic vase on a wall behind him. Next to the bottom of the image, an answer says, “No, I’m afraid of being left behind.” It is a response that resonates with the abandoned bouquet of flowers, as well as with the lonesome child.