Guest Relations at Dubai’s Jameel Arts Centre takes the opportunity to both explore and resist the generic nature of contemporary hotels in the era of globalisation by exploring the various histories and specific stories in which they are grounded.

When the world was on lockdown during the Covid-19 pandemic, my partner and I broke curfew and trespassed through an unlocked door in a Grand Hyatt near where we lived, exploring dining areas, the empty rooftop bar and the drained infinity pool of the all-but-abandoned hotel. Indulging in a bit of post-apocalyptic fantasy, we enjoyed the freedom to experience a normally restricted space. Similarly, Guest Relations offers the prospect of transgression and illicit access.

It is fitting that the exhibition is mounted in Dubai, a site with a recent history of intense and rapid touristification, as well as a place close to home for curator Murtaza Vali, who grew up in neighbouring Sharjah. As a former colleague who was part of Dubai’s early efforts to build a tourism industry from scratch once told me, the huge investments over the past couple of decades in air travel infrastructure, attractions and accommodations, as well as bundled services and special offers, has “worked”. In 2022, international travellers spent USD 29.4 billion in Dubai, according to the World Travel and Tourism Council.

Guest Relations centres on the ways in which, once established, hotels are the sites of, and convey, historical narratives, how they have acted as important communal spaces, and how they intersect labour and class. Themed galleries are inspired by the hotel building, lobby, corridor and room, while the exhibition also touches on vehicles of tourism, including airlines, cruise ships and social media.

The empty hotel as ruin is central to Hale Tenger’s Beirut (2007), a video showing the exterior of that city’s St Georges Hotel, abandoned during the Lebanese Civil War. In the wake of an explosion that killed Lebanese prime minister Rafic Hariri and further damaged the hotel, a UN tribunal investigation was underway and access to the site was prohibited. From where she was staying across the street, Tenger surreptitiously recorded a video of white sheets hung in the St Georges’ open windows fluttering in the afternoon breeze. Nighttime footage is overlain with sounds of explosions recorded when Israel invaded Lebanon in 2006. Abstracted from its social function, in this case by war, the hotel becomes a ghost with its own stories to tell.

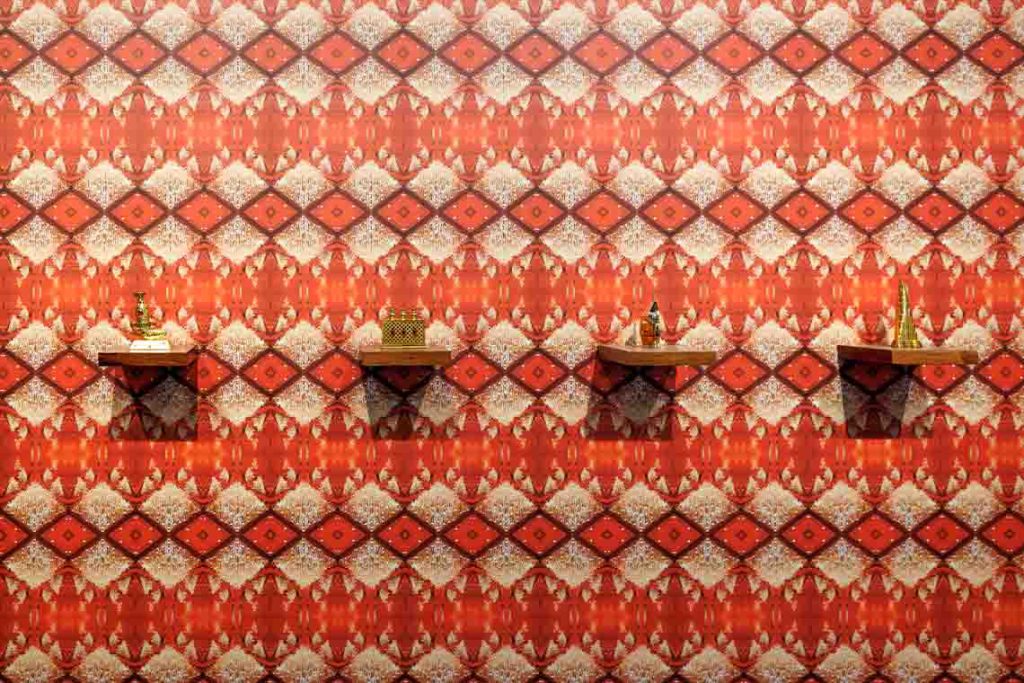

That hotels have been the sites of events with global significance highlights their role as engines of modernisation across the Global South and also the often-overlooked fact of their attendant historical narratives. The 1976 International Monetary Fund Meeting, for instance, announced the entry of the Philippines into global capitalism, inaugurating the enormous outflow of Filipino workers who have been integral to the growth of cities like Dubai. Combining wallpaper showing the central chandelier of the hotel where the meeting took place with gaudy perfume bottles modelled after iconic Dubai buildings, including the Burj Al Arab, Pio Abad’s Oh! Oh! Oh! (A Universal History of Iniquity) (2013) comments on the emptiness created by the debasing effects of the creation and satisfaction of tourist desire.

Ahmed Mater’s Abraaj Al Bait Towers (2012) shows us hotels that threaten to deplete Islam’s holiest site of its spiritual character. The Ka’aba at the centre of the holy city of Mecca is visible through a narrow opening between hotels that are part of the large-scale urban development taking place around it. Recalling Tali Keren’s efforts to probe understandings of the Holy Land in works such as Un-Charting (2023–ongoing), Mater’s photograph begs ideological questions about the role of the hospitality industry in a reshaped Mecca.

The transgressive thrill of trespassing runs through several works, including Mati Jhurry’s research-based pieces, which take cues from artists like Sophie Calle (whose work also appears in Guest Relations), blending performance with the act of archiving the hospitality work that often goes unseen by travellers. For Lavatory videos from the archive of ‘Emirates staff No. 460956’ (2023), Jhurry worked for Emirates airline as a member of the flight crew. During her three-year contract, she methodically catalogues her labour in video and text. In reconstruction: Crew Rest Compartment from the archive of ‘Emirates staff No. 460956’ (2023), one of the exhibition’s several commissions, Jhurry collaborated with artist Nabla Yahya to recreate, from memory, the onboard compartment where crews are required to rest during long-haul flights.

Sung Tieu’s chilling Moving Target Shadow Detection (2022) takes us through an empty version of the famous Hotel Nacional de Cuba in Havana, where the first sonic attack causing the Havana Syndrome that has mysteriously afflicted US government personnel abroad, reportedly happened. With access impossible due to the Covid-19 pandemic, Tieu digitally recreated the Nacional’s interior, including a hotel room gradually turning white, as a menacing gas pours from air conditioning vents. Embodied by the drone we see when passing a mirror in the hotel, we as viewers are allowed into both an off-limits hotel and an occluded history of espionage and secret warfare stretching back to the Vietnam War.

Guest Relations lets us not forget that, for some urban residents, hotels hold fond memories, countering the view of them as hollow vehicles of tourism. In Hind Mezaina’s Good Life (2023), advertisements in the back of issues of the Dubai-based What’s On magazine invite Western expats to hotels for performances by the likes of Tina Turner. Part of an earlier work focusing on Sharjah’s nightlife in the 1970s and 80s, the ads demonstrate the diverse social roles hotels took on in the UAE’s earlier decades, when they acted as both communal (though exclusive) hubs, as well as entry points for new practices or ideas into society.

These and the many other works in what is a crowded exhibition make Guest Relations an invitation to understanding the complex histories hotels have had in cities and the lives of their inhabitants. Like exploring an empty hotel for a thrill, the exhibition allows for a normally impossible deeper consideration of all that is part of the hotels that make guests feel comfortable in their visits to destinations near and far.