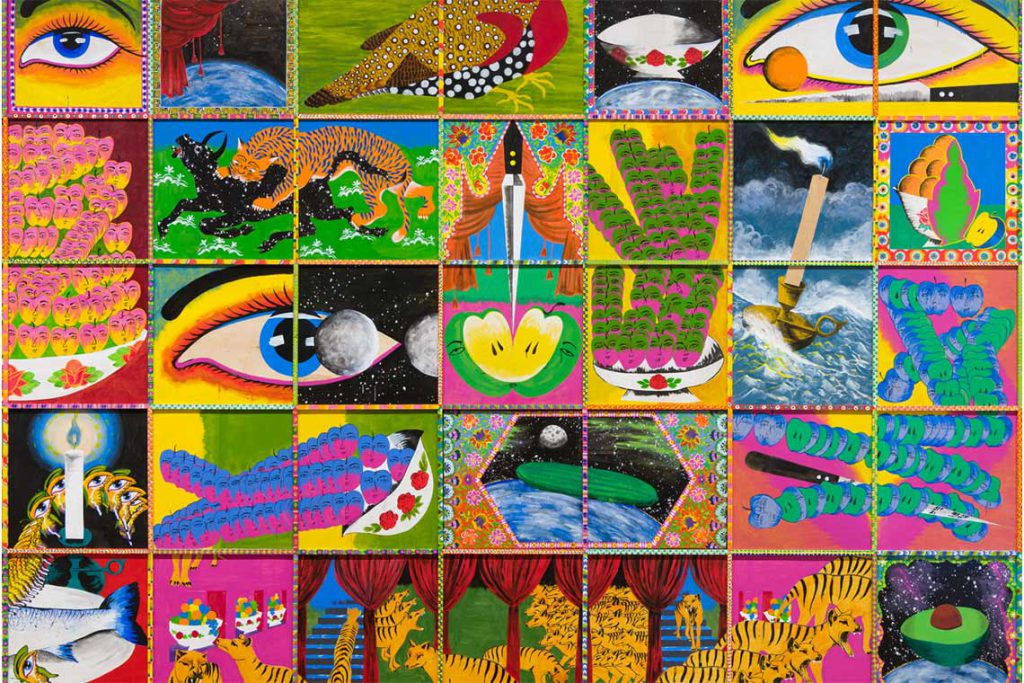

The visual lexicon of the Iranian-born New York-based artist shows an effortless commitment to illustrating flora and animal life within fantastic vignettes.

Canvas: You have long been using elements that are considered ornamental in your painting. This imagery is common among contemporary painters now, but this was not always the case. What was the general reaction, especially from Western audiences, to your early paintings?

Iman Raad: What has stuck in my mind is that I’ve been told several times that my art is “only beautiful”. I’ve revisited this comment repeatedly to reassess my work in relation to the dominant audience of my art. The notions of ‘beauty’ and ‘ornament’ are often profoundly misinterpreted when a work is viewed through the Euro-American-centric lens. In the ‘West’, beauty and ornament are seen as secondary to a primary meaning or truth, whereas in the ‘East’, ornament is the meaning itself, preceding any content it might convey. As you mention in your question, beauty and ornament are fundamental to my practice. They are not merely vessels for symbolic meaning, as is often assumed, but themselves constitute the meaning of my work. My art often disappoints audiences who are eager for symbolic content, and as a result, they sometimes find it meaningless.

However, this struggle is not as foreign to Western audiences as it might seem. For instance, the Pattern and Decoration feminist art movement, which emerged in the USA in the 1970s in reaction to the white male-centric nature of modernist art. It’s no surprise that I, along with many artists from other non-dominant cultures, share this fight with female artists. In 1908, Adolf Loos, an influential figure and theoretician of European Modern architecture, wrote in his infamous book Ornament and Crime, “I can accept the ornaments of the natives, the Persians, the Slovak peasant woman, and my shoemaker’s ornaments, for these workers have no other means of reaching the heights of their existence. We have art, which has replaced ornaments.” This quote is an example from the history of modernism that gathered the so-called ‘others’ under the umbrella of ‘ornament’.

You attribute a human agency to flowers and birds, which gives a surreal twist to the paintings. Could you talk about the power you find in fantastical imagery?

Soon after I found myself in the US pursuing my master’s degree in painting, a form of refusal evoked within me against the enforcement of dominant artistic discourses and the imposed politicisation of my identity. While I rejected prescribed roles, as someone politicised by fate I still wanted to express myself in a politically active way. I aspired to create socio-politically conscious art while avoiding the prevailing artistic waves. As a result, I began painting non-human entities such as fruits and birds, attributing human characteristics to animals – what is known as anthropomorphism in literature. We see this approach in authors, especially those living under totalitarian regimes, writing animal characters to bypass censorship or save their lives while still preserving their freedom and their ethics. Inspired by storytelling, I chose not to paint human figures as a way of evading the pressures of dominant value systems.

Surrealism often comes up in conversations about my work, and rightfully so, as I connect with it as a genre that emerged in the aftermath of war, seeking to disrupt the dark reality of its time. Additionally, it resonates with me due to its association with psychology. My inclination toward surreal imagery began as an act of refusal and has since evolved, linking my work to both surrealism and the European still-life painting tradition, as well as Qajar painting from Iran.

We live under an endless influx of imagery and data through the internet. As a painter, how do you find a balance between inspiration and reaction?

The nature of my work is not impulsive, but that doesn’t mean I’m unaffected by the daily data that I’m exposed to and the hectic flow of social media. As you mentioned, the important question is how to maintain a balance – staying aware of what’s happening in the world while preserving a slow, intentional practice. When I was at college, I became fascinated with Systems Theory and the theory of complex systems. These had a major influence on how I understand myself as an artist in relation to the flow of information I receive from my surroundings, and how my brain digests and transforms that into artistic outcomes. I brought these ideas into my daily life and practice by, first, intentionally governing and curating the images and cultural products I consume. That, like an athlete’s diet, artists should carefully control what they observe and absorb. And second, by strengthening my individuality. The pressure of the internet today is overwhelming and, for many, unbearable. What was once a hopeful system for the democratisation of information has evolved into a giant, amorphous set of repressive algorithms. It’s more complicated than ever to govern our visual feed and track how this endless influx shapes our vision. I’ve noticed several artists around me distancing themselves from social media and shifting toward slower learning and production. I would say that ‘slowability’ is a key factor in finding a balance between inspiration and reaction.

How do you wrestle with the common expectation to produce immediately socio-political work because of your home country?

As an Iranian living in New York, I navigate a politically saturated world where identity is not only a matter of personal existence but also a political and media interest. The marketplace often legitimises art that engages directly with one’s identity. By rejecting the value regime of the art world, an artist must fill the theoretical gap around their work. In the 1980s, American philosopher Arthur Danto asserted that theorising around art would eventually take over the function of the work of art itself. Referring to Danto, art sociologist Pascal Gielen, in his book The Murmuring of the Artistic Multitude, argues that contemporary artists rely heavily on communication, verbal skills and the performance of their ideas as artistic value has shifted from manual skills to verbal skills. Today, artists are expected to be adept performers of their ideas above all else.

This aspect of the art world is deeply discriminatory, as many artists from various cultures struggle with the lack of relevant discourses inside the dominant interests of the art world and therefore they have to choose to either assimilate into the dominant regime or to be marginalised. It’s obvious, yet important to voice, that a system that prioritises verbal skills inherently undermines non-English-speaking artists. However, there may be strategies or approaches that artists from other cultures, like myself, can adopt to legitimise their work outside of the repressive expectations of the dominant value regime. This, however, comes with the burden of convincing the art world – a challenge that requires patience, strength and self-motivation. One must also be prepared to pay the cost. A brutal reality about art in the present day is that an artist’s life, soul, self and body are inherent materials of their work.

Repetition is a strong motif in your work, with objects or birds being echoed in a single painting. What does repetition mean in your lexicon?

In those moments, my aim is to create disruptions in reality – the instant when familiar reality ruptures. It’s the moment when our understanding of ‘self’ shatters and the rigid sculpture of the self begins to crack. It refers to one’s own reflection in a mirror: flat and multiplied.

What kind of inspiration do you find in New York, where nature hides behind grit and urbanism?

People. So many wonderful people. As well as art events, plays, operas, concerts, movies and galleries. And my students who make me believe in the future.

This interview first appeared in Canvas 115: On the Wild Side