Deconstructing anthropocentric readings of the urban landscape, Three Tired Tigers at Jameel Arts Centre explores Dubai from the viewpoint of our non-human neighbours, asking who really holds the power.

“Dubai is a city I find fascinating for its unique coexistence, where animals carve out spaces to thrive within the gaps of urban design, and local communities show incredible care and compassion for street animals,” says Lucas Morin, exhibitions curator at Jameel Arts Centre. Home to tens of thousands of street cats and itself nicknamed the Gulf Tiger, Dubai does seem an apt location for Jameel’s animal-centred show, Three Tired Tigers. Curated by Morin, the exhibition brings together more than 40 artists and collectives – whose work largely “centres on cities and countries, primarily in the Global South, where animals continue to play a significant role in daily life,” Morin explains – to confront and upend our human-focused understanding of urban landscapes. They invite us to see cities from the perspective of the wildlife that, despite human attempts to exert control, has adapted to survive and even thrive. What would happen if we sought true coexistence with the animals in our midst, rather than distance and domination?

Three Tired Tigers is divided across five galleries that, as Morin explains, “guide you through urban spaces where animals are encountered”. We start in the zoo and museum, places understood as either of care and conservation or of classification and control – although, perhaps, these are two sides of the same coin. Depicting zoos in Palestine, Switzerland and Egypt, Noor Abuarafeh’s video Am I the Ageless Object at the Museum? (2018) centres on the zoo and its historical relation to the museum – both institutions that collect, and uphold a power imbalance between the collector and the collected – and the parallels between museums and cemeteries. Like cemeteries, the narrator says, museums are “nothing but the buried shape of stories”.

Tools of classification and control can be turned against humans, however. In a similar vein to Khalil Rabah’s Gaza Zoo Sculpture Garden (2017), which highlights the irony of public outrage regarding the plight of starving caged animals when the Gaza Zoo closed after Israeli bombardment, seemingly overlooking that Gaza’s population are themselves held in captivity, Madhumala Mandal, Rebati Mandal, Selo Yadav, Sudhira Karna and Sumitra Yadav use depictions of coexistence with animals to highlight their own oppression. In their 2023–24 works presented here, the artists (part of a wider women’s collective in Nepal) devise vibrant scenes where both real and imagined animals take on central roles in daily life. In doing so, they draw parallels between the classification and control of animals and the ways in which human lives, particularly those marked by marginalisation, are similarly constrained by social hierarchies, in this case by intersecting systems of caste and gender oppression.

Image courtesy of the artist and Art Jameel

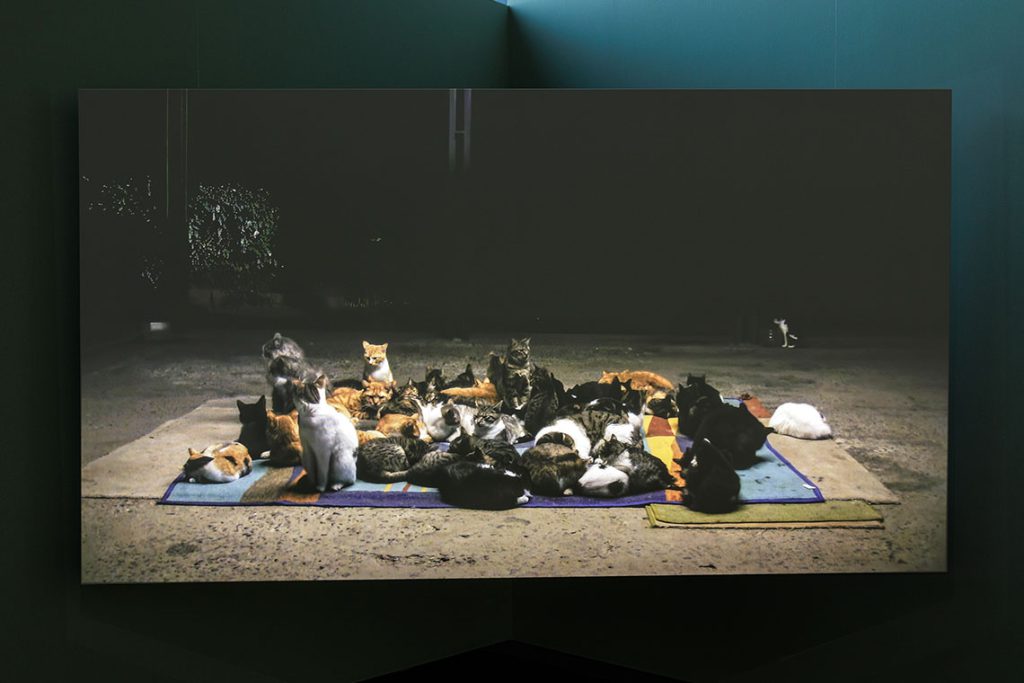

Attempts to control and contain prove futile. “From the outset, you’ll see what happens when some evade their cages, both literal and metaphorical,” Morin says. Building on the first gallery’s uncovering of a certain affinity between animals and (some) humans, as beings equally subject to systems of control, the next reveals what the curator calls “surprising networks of care and coexistence” on the street. In particular, it’s street cats that take centre stage in this section, with Morin pointing out that the whole show was inspired by the street cats of Dubai. “Even though the city wasn’t designed for them,” he says, “they are everywhere.”

The room’s centre of gravity is undoubtedly Annika Eriksson’s video The Community (2010), which captures a gathering of abandoned domestic cats in a park in Istanbul – a city famed for its feline population, but where cats are increasingly relegated to the outskirts or to parks amid rapid urban change. Eriksson’s work highlights, as she tells Canvas, “how the animals live in an uncertainty of terms between care, dependency and precarity”, but nonetheless find themselves in community. “The ‘community’ references both the community of cats and the humans who were feeding and trying to protect them,” she explains.

Putting the theme of interspecies solidarity into a more local context, in For Cats Only (2024) Khalid Jauffer presents an inventive solution to helping the street cats of Dubai, where residents can be threatened with fines for helping the strays. He has designed what he calls “anonymous shelters” for stray cats that blend seamlessly into the human-centric architecture of the street, where cats can “just hang out without being bothered by people” and find refuge particularly “during harsh summers and winters”.

The third gallery, which Morin dubs “the palace and the public square, where animals often embody power, values and history”, somewhat uncomfortably brings to mind the three lions on the England football shirt – and the flimsy foundations of national identity and mythmaking more broadly in my home country. While Kadhim Hayder’s oil painting Fatigued Ten Horses Converse with Nothing (1965), centres horses – rather than their knight riders – as symbols of martyrdom and resilience, Pilar Quinteros’ Tigres Prestidigitadores (Conjuror Tigers) (2019) playfully explores and underlines how animals often serve as potent symbols of prestige and national narrative. The inflatable sculpture and video use the iconic bronze lions of Santiago, Chile, as metaphors for colonial spoils and political legacies. These statues, believed to be war trophies looted from Peru after the 1879 War of the Pacific, are reimagined by Quinteros in an act of restitution.

Image courtesy of the artist and Art Jameel

By humorously ‘returning’ the lions to Lima, he critiques both colonial conquest and the neoliberal turn under Pinochet, reframing the lions – once symbols of imperial power – as wobbling, unthreatening creatures that question the structures of authority. Meanwhile, Shimabuku’s whimsical video Then, I Decided to Give a Tour of Tokyo to the Octopus from Akashi (2000) explores themes of communication and reciprocity. Taking an octopus on a day trip from Akashi to Tokyo, the artist reflects on the absurdity of human efforts to engage with the animal world, suggesting that while humans imbue animals with meaning, the animals themselves remain silent witnesses to these constructed narratives. Through these works, animals become both emblems of historical power and vehicles for subverting and questioning national mythologies.

At the edges of the city, the fourth gallery’s focus, animals stake their own claim to the urban landscape, challenging – if sometimes imperceptibly – human dominion and revealing the often invisible forces at play. In SUPER RAT Scrap & Build (2006/2011) by Chim↑Pom, a taxidermied rat (named Ken, which is a nice detail) is painted as Pikachu – a symbol of Japan’s pop culture – and embodies a critique of Tokyo’s polished, sanitised urban image. The rats, resilient to toxic poisons and thriving in the city’s sprawl, are not only the epitome of survival in a landscape designed to exclude them but also assert agency in an environment that seeks to control them. Similarly, Robert Zhao Renhui’s A History of Cows (2024) examines the forgotten role of urban cows in Singapore’s past, tracing their historical presence alongside marginalised communities. The death in 2016 of the city-state’s last ‘wild’ cow symbolised not just the demise of animal life but also the invisibility of certain social groups in the city-state’s rapidly urbanising landscape.

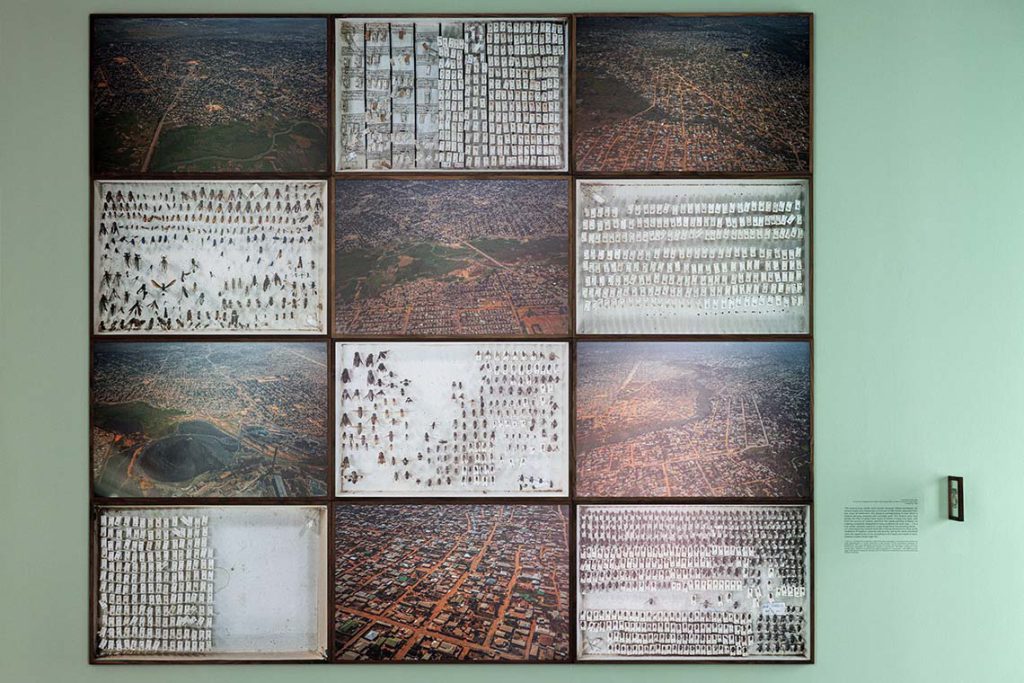

Lastly, Sammy Baloji’s photographic installation Essay on Urban Planning (2013) interrogates the legacy of colonialism in Lubumbashi (Democratic Republic of Congo), where the “sanitary belt” – a green strip of land designed by Belgian colonists to segregate the population, depicted in aerial photographs along with mosquito specimens – serves a powerful reminder of how animals have been used to justify urban planning and racial separation. Together, these works show how animals might quietly assert their place in the urban landscape and challenge the ideologies that shape our cities – or be weaponised to bolster those same ideologies.

Image courtesy of the artist and Art Jameel

Although the sky stands as a symbol of freedom and boundless possibility, Morin argues that it is also a “tightly controlled ecosystem shaped by typically human paranoia, surveillance and infrastructure”. Farah Al Qasimi’s photograph Falcon Hospital 2 (Blue Glove) (2016), depicting a falcon held by a veterinarian in Abu Dhabi, reflects the tension between the birds’ ancestral ties to the wilderness and their commodification within a human-made ecology. While falcons symbolise national pride and freedom in the UAE, their status as prized possessions in a regulated trade highlights the paradox of control over nature.

Heba Y Amin’s As Birds Flying (2016) explores this theme further, drawing from a sensational 2013 incident in which a stork, suspected of espionage due to an electronic tracking device, was detained in Egypt. Through a blend of drone footage and social satire, Amin reveals how the sky – once a space of migration and autonomy for these birds – has become a battleground for political control and surveillance. Similarly, Walid Raad’s We Have Never Been So Populated (1997/2020) reflects on the use of invasive bird species, such as parakeets, in the Lebanese Civil War, where birds were allegedly bred for biological warfare. Through this eerie historical narrative, Raad critiques the manipulation of natural life and the ways in which the environment itself becomes weaponised. Together, these works reveal how the sky, far from being a boundless realm of freedom, is intricately bound to human-imposed boundaries, surveillance and the exercise of power.

Leaving the fifth gallery, it might be tempting to think that humans have the last word. Jauffer’s Cats (2022), portraits of cats placed at cat’s-eye level and peppered throughout the show; and Jason Dodge’s Tiger Door (2016), a “big cat”-sized cat flap to an enclosed space built into the gallery’s architecture, visible both in the middle of the show but also, necessarily, when entering and exiting, hint at the felines’ presence – brazenly flouting Jameel Arts Centre’s “no animals” policy (which has an exception for service animals, if arranged in advance). As I step outside the building, I realise I’ve missed an artwork. Morin explains how Mark Salvatus’s site-specific outdoor installation Claws (2016/2024), made up of stacked wooden tables, is “a public installation where the cats themselves become active participants”. Sure enough, in the gentle warmth of the evening one of the neighbourhood’s resident cats is napping atop one of the tables. Even Gulf tigers need to snooze, I guess.