Looking to affirm senses of place and ownership, the artist immerses herself in a watery world of story-telling.

Jumana Emil Abboud first returned to the folklore of her youth when she returned to her childhood home. Born in Galilee to Palestinian parents, her family emigrated to Canada, where she started making work as a practising artist. “Then, an interruption, because my father passes away, and another interruption, we decide to go home”, Abboud tells me in her studio at London’s Slade School of Fine Art. “Our mother needed to reconnect with the larger, extended family, she needed the social bond. I can understand the need for that even more now,” she says. Abboud is a Palestinian citizen of Israel, which means she has “citizenship, quote unquote” and is permitted mobility across the country, as well as internationally, due to the ID card she holds.

Returning home from Canada made her aware of what we take for granted, and raised questions about mobility, freedom, segregation, discrimination, and “the denial of movement in your own home”. “What does it mean to live as a Palestinian? Where do I feel at home? What does home mean to me?” This questioning led Abboud to consider what made her feel good, safe and happy as a child: “It was stories”.

The artist has worked with folklore for more than 20 years, interested in how mythical archetypes and language can be translated through art practice, bring together and reaffirm communities, and contribute towards an embedded understanding of, and connection to, land. Working with drawing, video, performance, workshops, objects, storytelling and improvisation, Abboud’s work is grounded in stories from and of Palestine, while embracing folklore from around the world, whether that is through conversations and workshops or retellings of mainstream, popularised stories like Rapunzel, through which Abboud explores domesticity in the life of Arab women.

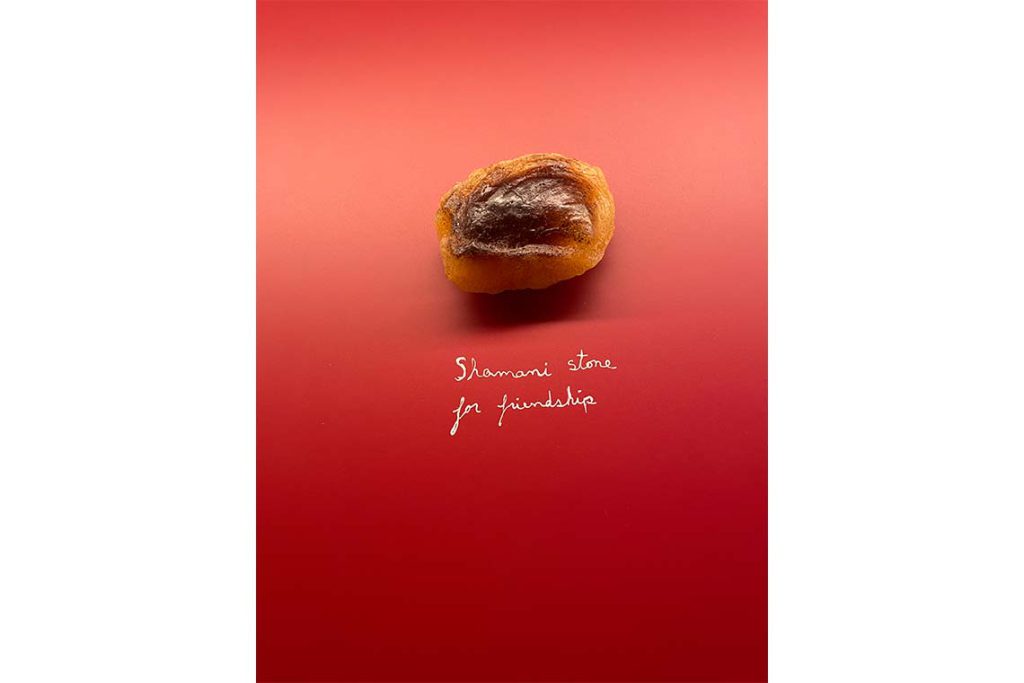

The Shamani stone (fossil stone talisman). 2022. Beeswax. 7 x 5 x 3.3 cm. Produced during a workshop at documenta fifteen, Kassel, 2022. Image courtesy of the artist and Issa Freij

In her drawings, Abboud revisits folktales, water lore and landscapes, not illustrating literal depictions of character but exploring “nuances of the tale vis-à-vis the present-day landscape of settler colonialism in Palestine”. Humans, animals and spirits are entangled with each other, and natural materials become both method and author: “I have been working with pomegranate ink, and as I handle the material, I am not working alone,” she explains.

“I am co-making with the pomegranate — the fruit, the tree, the land that held it, the water that fed it. Perhaps it is like calling on the spirit of the pomegranate… a physical, and a metaphysical being.”Abboud’s own life story is central to her practice. “It took me a long to time to realise, but then it hit me that all my work is semi-autobiographical,” she tells me. “As a child, social bonds were formed and thrived in nature, among the wild, and sometimes in defiance of our elders. They would say ‘Don’t go to that water, it’s where the goblin lives’, and the minute an adult says ‘Don’t go there’, we go. We would play and bond there.” Folktales rooted in sources of fresh water in Palestine, and about the goblins and ghouls that live there, form an important thread through Aboud’s work. Maskouneh – Inhabited (Hide your Water from the Sun), a collaboration with Issa Freij and shown at BALTIC in 2016, is a three-channel video piece responding to Dr Tawfiq Canaan’s 1920 study of water demons and ‘haunted’ sites in Palestine, including lost springs whose locations have been rediscovered through the retelling of folklore.

2014–17. Video still. Co-commissioned by AFAC, Bildmuseum Umea and Darat Al Funun – The Khalid Shoman Foundation. 2017. Image courtesy of the artist

An ongoing practice of water-divining workshops, revisiting water sources – physically and metaphorically – through collective storytelling and writing practices, have been hosted at Bétonsalon – Center for Art and Research in Paris, at Sakiya, Ayn Qiniya near Ramallah, at documenta fifteen Kassel and at Jameel Arts Centre, Dubai. Abboud’s PhD investigates the role of folktales as an empowerment device, specifically in the context of the broader historic Levant, acknowledging the multiple readings of the Arabic word for a water source ‘ayn’, which can also mean ‘eye’, and “juxtaposing the eye of sight with the source of water.”

Working from within occupied land, walking, gathering and living through segregation, erasure extending to people’s freedom to access their memories and imagination as the landscape itself is transformed beyond recognition, Abboud seeks to map land through stories “as a gesture of reclaiming and reunion, situating our connectedness to [and through] story heritage”. The nature of doing a PhD means that she has been able to commit to her practice full time and develop a sustained presence in the landscape and with her collaborators. “It is helping me to listen to all the voices in my head,” she tells me, “to my ancestors, and to people with whom I have worked on the ground in Palestinian communities.”

2020. Acrylic, gouache and pastel on paper. 76 x 57 cm.

Image courtesy of private collection

Abboud recognises her responsibility as an artist working with people living under occupation, and interrogates her position as an artist working in a “fragile space”. Her primary concern is conducting humane practices, and connecting with people and their surroundings in a meaningful way over a period of time. “It is all about connectivity,” she says, “which is what storytelling, mythology and folklore have always been about.” The stories being written, rewritten, told and retold embody the lives and memories of people, as well as memories of nature and lessons on how we live with nature, with the other and the more-than-human. “When we are not telling these stories, we are creating greater distances between our lives,” the artist affirms.

he water sources that form the focus of Abboud’s divining workshops are themselves endangered and part of the more-than-human community with which she seeks to practice in “ethical kinship”. Part of her methodology is a set of ideas that started as a manifesto and became ‘virtues’, religious or spiritual principles drawn from folktales. They are: trust in God – “whoever and whatever God is for you”, fortitude, strength of mind, patience and self-denial, the last one being Abboud’s favourite because of the questions that arise from its meaning: “Is it like submission? Is it renunciation? Not in a religious sense, but what would happen if an artist leaves the ego?” The virtues act both as a guide and something to challenge. They do not necessarily need to be agreed with, but are there to be “played with”, as she puts

Abboud’s practice of collective storytelling, community writing, co-authorship and co-belonging acts as a rejection of ego, or a rejection of the myth of the singular genius; collective writing embracing improvisation, imagination, invention. While her practice often involves acts of what one might see as a sense of return, it is not nostalgic. She recalls stories in order to reawaken them, to let them change, grow and live. “The small mythologies of our migration hold [us] into being,” she says. “When you are pushed out of your land, stories connect you.”After a pilot project during a fellowship in Paris, Abboud held the first water-divining workshop in Ayn Qiniya, a village near amallah. She was hosted by Sakiya, a progressive academy that connects “local agrarian traditions of self-sufficiency with contemporary art and ecological practices” and which has agreed with the family who own the land on which it works that it will undertake re-wilding and protect its water source. Sakiya’s presence in the village serves a greater purpose for Ayn Qiniya and its ecosystem; by sustaining activity in the valley, they are protecting the village, the olive groves, and water sources as “illegal settlements on top of the mountains will take over” if the area appears to be out of use.

There are seven springs of water connected to the valley, and since the residency Abboud has been working with them as sources of continuing stories. In the workshops she leads, she makes use of exercises, play, observation, improvisation and games. “It is not all about who can write or who can draw,” she notes. Participants use language, gesture, sound and the collection of objects that inspire writing or are cast in moulds as wax talismans, Abboud’s main desire being “to enable a space where a collective of people can imagine together”.

As the water-divining workshops continue internationally, through storytelling, performances and rituals, Abboud is considering how to work with – or through – all her ‘virtues’. Part of that involves returning to Palestine, to Ayn Qiniya, and talking through the virtues with her collaborators. Being grounded in, and connected to, the landscape of her work, the human and more-than-human life that contributes to it, is essential to Abboud’s practice. “There’s something of a mycelium – as in the roots of trees – in human bonds, and how that enables and strengthens our sense of belonging,” she explains.

This sense of belonging also carries a mantle of responsibility, to represent the erasure of indigenous life through colonialism. Although Abboud’s work, in each of its forms, is not directly political, it is inherently so in how she illuminates stories, traditions, water sources, land and history. Her ongoing presence, both physically and through the retelling of stories, refuses erasure. “I had started [the water-divining] project wanting to offer hope,” she says, “and I too am a Palestinian who needs hope, but I don’t want to look for hope through outside sources. I don’t want hope as a denial mechanism. I want to say: ‘How can we as a community rely on each other, reinstate hope for each other?’ It is not that hope is a negative word. It can be a magical place, which we can get to because we need to, but how can we live now? ”

This profile first appeared in Canvas 109: Smoke and Mirrors