Blending Egyptian abstraction with Italian craftsmanship, the artist confronts the complex interplay of memory and trauma.

Canvas: You initially pursued business studies before undertaking a postgraduate degree in restoration and then turning to art. How did the masters and your subsequent training in Italy influence your approach to sculpture?

Khaled Zaki: I studied scientific subjects in high school and originally wanted to become an architect, which might explain why I’m now also involved in design, alongside sculpture and jewellery. I went into business studies and earned an MBA, but then decided to do a Masters in Restoration at the Faculty of Archaeology at Cairo University.I chose that subject because I was more interested in engaging deeply with heritage, especially ancient Egyptian culture, rather than pursuing formal academic art training. I realised that I did not want theory, I wanted practice, and so travelled to Italy to gain experience, especially as I knew that, when I returned to Egypt, I would likely be working alone. So I went directly to the workshops and asked to learn by working. I worked twelve hours a day, alongside major artists and technicians who taught me how to feel and understand stone, its grain, its sound and its appearance. I still carry that knowledge with me and have come to believe that I must pass it on to the younger generation. It would be a shame if it disappeared with me, especially now that robots are everywhere. The sensitivity to stone is a feeling that can never be replicated by a robot.

In your Resurrection series, the body appears both broken and healing. How do you use the figure to explore collective memory and societal transformation?

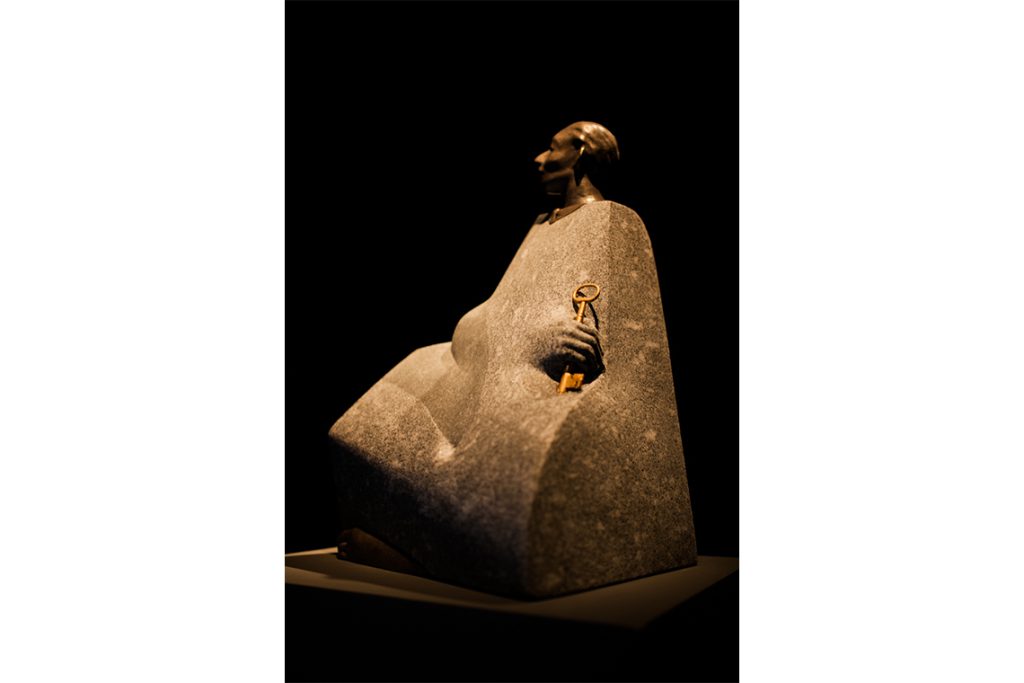

Take the Egyptian revolution. It was inspiring at the beginning, everyone was rebelling, wanting a better life, believing we deserved a better future. That energy moved everyone. At the time, I was sculpting The Sitting Patriot (2011). It shows a figure seated, somewhere between rising and collapsing, neither standing nor lying down. However, I wouldn’t say that the revolution itself was the origin of the Resurrection series. For me, everything started with the Palestinian situation. That is the central issue in the Arab world and the Middle East, whether we admit it or not. I was born in Suez. After the 1967 war, we were displaced and we returned only after the 1973 war. So you can say that this idea of breaking, disassembling and reassembling has been with me since birth.

28 x 59 x 56 cm. Image courtesy of the artist and Tabari Artspace

What stands out most when you think back to your mentorship with [leading Egyptian artists in glass and sculpture] Zakaria Al Khonani and Dr Aida Abdel Karim? Was there a defining moment or piece of advice that has stayed with you?

In the summer of 1982, before I started studying business, I went to Alexandria for a holiday. Every evening before sunset I’d go to the beach and sculpt figures in the sand, when most people had already left. One day I was sculpting when I heard someone clapping and encouraging me, saying, “Wow! We have an artist here! Are you studying at the Faculty of Art?”. That woman was Professor Aida Abdel Karim, with her husband, Zakaria Al Khonani. Their villa happened to be close to my aunt’s villa, where I was staying, and a few days later Aida came to visit us and saw my drawings and sketches. She told me, “You are an artist. You were born an artist. Come to our studio.” Their studio was in Harraniya, very close to Cairo University, and afterwards I used to go there every weekend for four years. I was so lucky to have met them. They were exceptional, not just as artists but as human beings. Through them, I learned not only technique but also the ethics of being an artist, how to live with integrity, discipline and humility. Zakaria and Aida advised me, “If you want to go abroad to learn and build a career, the only place you should go is Italy.” That advice shaped my life. In 2015, I was the one who carried Aida’s body at her funeral, to her final resting place. She had given me so much, it was the least I could do.

In 2013, you represented Egypt at the Venice Biennale. What was that experience like for you, personally and artistically?

I was selected to represent Egypt just as everything was collapsing politically. It was right before the 30 June revolution, when people were in the streets protesting against the Muslim Brotherhood government. Morsi was still president, but the resistance was building. When I arrived in Venice to install my work, the revolutionaries had stormed the Ministry of Culture in Egypt. The Minister of Culture, a Muslim Brotherhood appointee, couldn’t even enter his office. Everything was chaos, but we had no choice but to move forward with the exhibition. That was the first time I showed my Sufi sculptures and the Sarcophagus series. I had a huge six-metre sarcophagus, covered in gold leaf. Looking back, I think it would have been even more powerful if it were just raw, rusty steel. But at that moment, I wanted it to shine. The sarcophagus in ancient Egypt is a symbol of resurrection and renewal, from a temporary life to another immortal life. The Sufi figures were about peace, tolerance and transcendence, qualities that I felt were being lost in the violence and extremism of the time. I curated the pavilion myself, due to the circumstances, and worked with mosaic artist Mohamed Banawy, who created beautiful works representing the Nile Valley.

How was your transition from representational sculpture to abstraction reflected in your artistic thinking?

In the beginning, when I first arrived in Italy, I was heavily influenced by my surroundings – Greek and Roman classical forms, white marble, lots of plastic and anatomical detail. I had not yet developed a clear identity. I was just absorbing and trying out new things, doing pieces inspired by nature, shells, plants, that sort of thing. I was discovering myself. Eventually, I realised that the Egyptian heritage is deeply abstract. There is a strong clarity and minimalism in ancient Egyptian art. I began to feel a responsibility to represent that, as well as acknowledging that Egypt went through 800 years of Greco-Roman Mediterranean influence. After the Sufi series, I was actually worried about how the Resurrection series would be received, because it was so different. But collectors who loved my Sufi works also responded positively to Resurrection. They understood it came from the same source, which gave me the confidence to keep going and to trust what I feel.

Are there any upcoming projects you’re working on that you’re excited to share with us?

Yes, I’ve started carving new works inspired by seashells. This was how I first began when I arrived in Italy back in 1988–89. Those were my very first pieces, just a young boy trying to find his voice, exploring form and material. Now, after decades of experience, I’m revisiting those early ideas with new depth and clarity. The shapes are more minimal, more refined, but they still carry the memory of those beginnings. It is a return to my roots, filled with both confidence and nostalgia. I am back to the future.