Under the lead of director Qudsia Rahim and curator John Tain, this year’s Lahore Biennale urges us all to come together as a community and find ways to exist in the face of climate change.

Recent decades have seen natural disasters become more powerful and deadlier, from flooding and uncontrollable wildfires to typhoons and, prior to the opening of the 3rd edition of the Lahore Biennale, the unprecedented destruction caused by Hurricane Helene that in mountainous areas of North Carolina in the United States that had never experienced such a phenomenon.

As curator John Tain pointed out during the opening, nature is no longer predictable. We must therefore learn from each other, and try to coexist with the environment and embrace change rather than resist it. “The climate crisis is not just about the weather. [The unpredictability] is a new situation in places like North America and Europe, but this is nothing new for many parts of Asia. We have in our histories a long legacy and remembrance of living and surviving,” Tain explained. This year the Lahore Biennale, entitled Of Mountains and Seas, presses on urgent issues relevant both in the region and on a global scale. It offers a range of critical perspectives from Pakistan and the Global South, such as how we look at nature and what it means to coexist with climate change as we seek to address the impacts of our relationships with different spaces and each other. It is a story of resilience and adaptation as the international community seeks to reimagine a sustainable future. “The artists who I invited have the knowledge to share with us,” continues Tain. “The climate crisis is not about a single country, it doesn’t care about borders and it does not discriminate. We need to learn and work together.”

Image courtesy of the Lahore Biennale Foundation

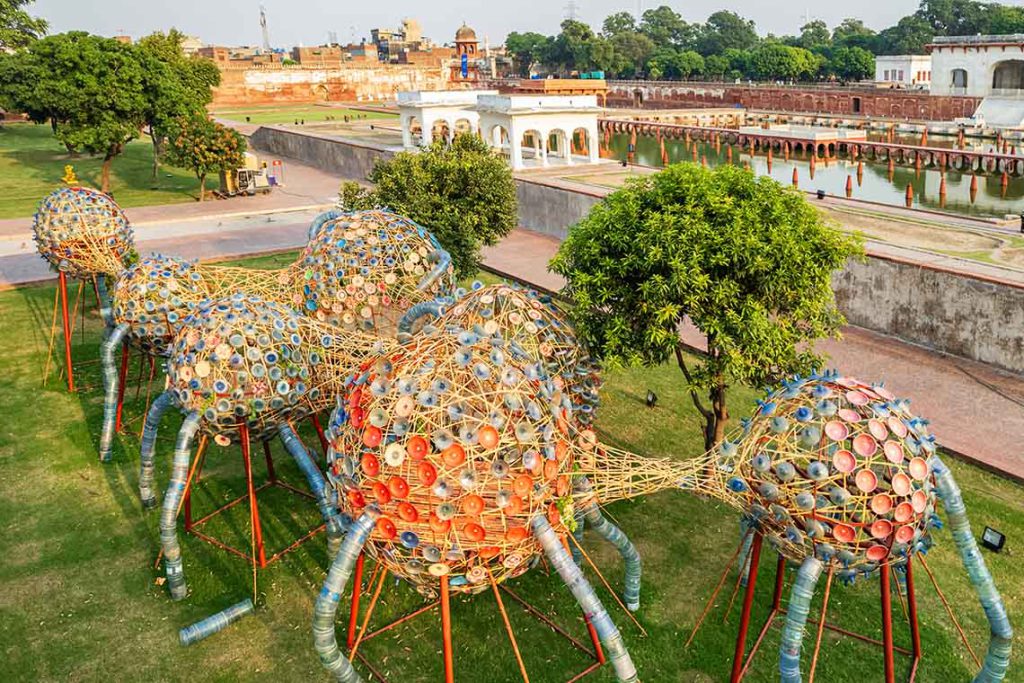

This year around 60 artists came together in dialogue with the historic city and its venues, such as the YMCA and Lahore Fort, with works placed for the first time ever in the Mughal Shalimar Gardens. The pieces notably interacted with the architecture of the UNESCO World Heritage Site and engaged with the community, such as Shalimar Flow by Daniel Otero Torres site-specific fountain intervention, Hamra Abbas’s 11-panel monochrome marble series entitled Aerial Studies (2024), which leans in stark contrast against the garden’s red brick walls, highlighting the vulnerability of mountain ecosystems – specifically in the Gilgit-Baltistan region of Pakistan, which is facing melting glaciers and flood risks; or Leeroy New’s Mebuyan’s Colony (2024), an interactive installation consisting of upcycled materials that invites visitors to climb inside and explore the structure of giant spheres on bamboo and metal stilts. The work references Mebuyan, a goddess of death and fertility in Bagobo mythology in the Philippines, speaking to the cycle of life and our interconnectedness.

Placed in the pavilions in the gardens in harmony with the architecture, Hague Yang’s Spring Sailors – Six Synecologies Aloft (2024) reminds us that the world around us exists beyond the immediately seen. The delicate sculptures were inspired by Lahori kite design, drawing attention to the architecture and airflow of the location as well as to the air we share and breathe. The bells attached to each kite ring in the wind, reminding us of the sky above and the pollution that often plagues it. In the same vein, Dryden Goodwin’s Breathe: Lahore (2024) is a public series of posters depicting clean air campaigners as they inhale and exhale. The work is installed at various locations across the city, including in tunnels, at metro stations and on buildings’ facades, once again calling attention to environmental concerns that are invisible but very much felt.

Image courtesy of the Lahore Biennale Foundation

Exposure to the unseen elements is also exemplified in Trevor Young’s site-specific installation at Alhamra Art Center. Earth to Earth (2024) highlights resources we take for granted. Two sets of unfired terracotta pots are set across from each other on either side of a window, with one inside the building and protected in the gallery space and the other exposed to outdoor factors for the duration of the Biennale, in a time-sensitive observation of the climate – humidity, heat and microbes – of Lahore. It also speaks to the labour of firing clay and the use of heat to make it a useable object beyond a raw material that we often overlook.

Köken Ergun with Fetra Danu’s animated video China, Beijing, I Love You! (2024) takes on the Maritime Silk Road that historically linked key ports across the Malacca Strait and Indian Ocean and thence to Europe via Arabia and Africa, latterly through the Suez Canal. The three-year research projects discuss consumption, working conditions and environmental impacts of extractive economies profiting from the depletion of materials essential in the production of technology such as missiles, batteries and phones. An upbeat karaoke sequence sings out the mineral deposits in a flashy call to exploit: “Gold. Bauxite. Nickel. Copper. You name it.”

Tomás Saraceno’s Museo Aero Solar (2007–) occupies the Bradlaugh Hall, a space with a long history of political events and a forum for art and culture, which then turned into a grain storehouse and home for migrants and ironworkers until the area flooded in the late-1950s. Under current restoration from damage and architectural encroachment, the hall has been reclaimed by Saraceno’s artwork as a communal space for art and reflection. Plastic bags are dried and patchworked together in an accessible large inflated structure as the artist finds new ways to repurpose the material polluting our air, waterways and even our lungs through airborne microplastics. Visitors are asked to engage and draw on the plastic walls, creating conversations around community, cooperation, understanding of the sensitivity of our environment and how salvaging discarded materials may be critical for new ways of living.

Concern around water issues permeates works across the biennale. Ravi Agarwal’s I am Going to the Sea, Clear the Path (2024) highlights the plight of endangered Indus and Ganges River dolphins by tracing their evolutionary history and current threats from human activity, including political restrictions over waterways through dams and nets, artificial sounds and mechanical objects that hinder communication, as well as challenges brought by pollution, fishing and poaching. Madhu Abuzar’s Humming with Ravi (2024) similarly stresses the fragility of water with a focus on Lahore’s River

Ravi, which once supplied the city with its most precious resource. The performance piece saw the artist swathed in plastic and rubbish, as he draped himself over a wooden boat in an emotional plea and reflection on the impact of pollution on daily life.

“We all know about the 2022 flooding [in Pakistan], and this is something that became a central issue for us to think about. What does it mean to host [a biennale] in Lahore and why would we want to do so now?” mused Tain. “An important reason behind our position was that the Biennale is not just extra ornamentation that could easily be forgotten, but something that could contribute and give back to the community in the longer term.”

The works selected by Tain are not only prompting important conversations but also creating a community of dialogue between each piece. The artworks serve as a network for the flow of a thought-provoking topics across the biennale, and underlining the communal nature of the concerns and the desire to share. Running alongside the Biennale are several impactful collateral exhibitions taking place across the city, as well as public programming and a concluding climate conference. As Sin Wai Kin’s video commission The Fortress (2024) makes clear, arrogance, privilege and exploitation will only destroy us and in the face of nature we cannot act as individuals but must learn to respect and adapt collectively to the consequences of climate change.