Hashem Shakeri‘s Staring into the Abyss invites audiences to engage with Afghanistan’s reality beyond the headlines, offering a raw and intimate portrayal of life under the Taliban.

“If you stare into the abyss long enough, the abyss stares back at you.”

Friedrich Nietzsche

The title of Hashem Shakeri’s first solo UK exhibition, Staring Into the Abyss, draws inspiration from Nietzsche’s famous quote, reflecting what Shakeri calls the “darkness” and sense of “unending suspension” that he witnessed in Afghanistan following the Taliban’s return to power in 2021. Sandwiched between the diverse permanent collections of Bristol Museum and Art Gallery – seamlessly moving from Japanese porcelain and European Masters to life under the Taliban is quite the tonal shift – Shakeri’s show is visited not only by photography enthusiasts; on the “half term” (school break) Thursday when I visit, children dart in and out of the long, thin gallery that serves as something of a thoroughfare, their exasperated parents just happy to let them expend some energy on this very rainy Bristol day.

The banal normality of this atmosphere is, on one level, jarring against the content of Shakeri’s images. On another, it is utterly perfect. This collection of photographs, taken during a period of profound uncertainty when hopes of an open and more progressive Afghanistan evaporated seemingly overnight, resists sensationalism and the politicised spectacle so often associated with news coverage of the region. Instead, Shakeri’s images capture the melancholic aftermath of this historical pivot, focusing on ordinary – and always deeply human – stories. “I feel that the post-disaster moment carries a far deeper emotional and psychological weight than the disaster itself,” Shakeri tells Canvas.

© Hesham Shakeri

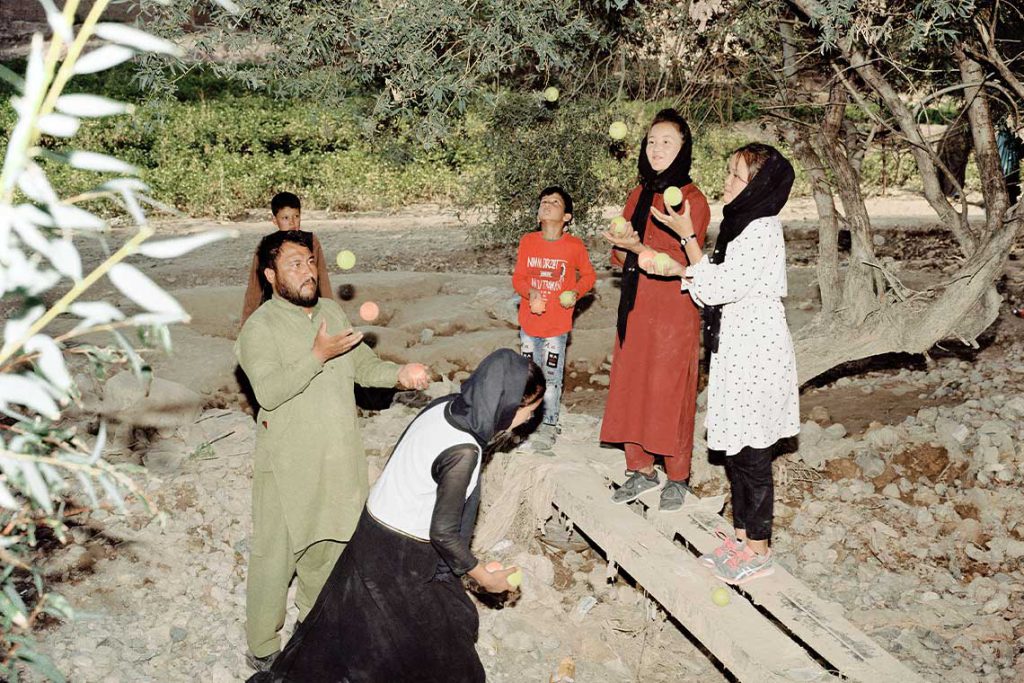

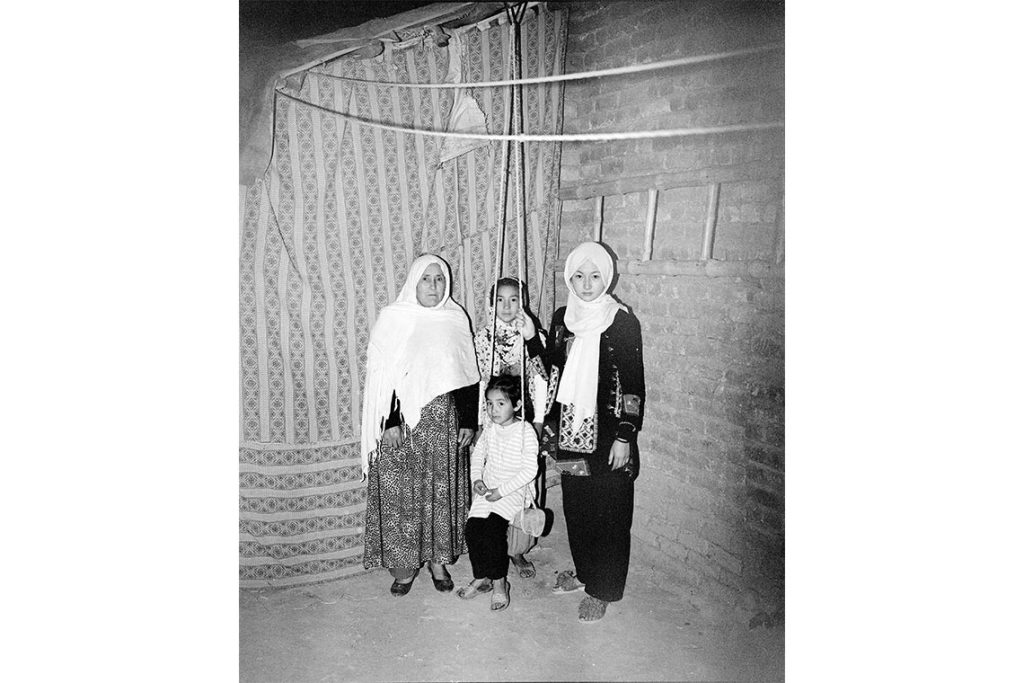

With women and girls facing particular restrictions under Taliban rule, including girls being systematically denied secondary and higher education, a particular focus on the female experience is par for the course. One image is of 13-year-old girls Hasti, Tahereh and Fatemeh secretly practicing circus sports in defiance of the restrictions on their education and social freedoms; another depicts 16-year-old Razia who, the caption explains, “has been fighting patriarchy from a young age and is documenting her experience as a woman under the Taliban”. In black and white, along with a minority but significant number of images in the exhibition, the photo of Razia looking directly to the camera, standing alongside other women in her family, has a stark quality, the intensity of her calmly defiant expression amplified by the lack of colour.

Women are not the only persecuted minority centred in the exhibition. Shakeri also sheds light on the experience of the minority ethnic Shiite Hazaras, displaced refugees and Afghan nationals in Iran. The image of young Jamshid, a 10-year-old guarding his family’s solar panel in a refugee camp, for example, encapsulates what the photographer dubs the “post-catastrophic moment”. The sun reflected by the panel blazes so intensely in the photograph that Jamshid’s form is nearly swallowed by a burst of orange and yellow light, evoking both the overwhelming conditions he endures and the loss of visibility that refugees often face in the global narrative.

Crucially, and perhaps uncomfortably for some, the individuals photographed – and afforded the same humanity – include the Taliban themselves. A gun lying on the floor, Taliban fighters crouch and share watermelon, the vibrant pink-red popping against the grey stones and black firearm; three young fighters keep watch on Wazir Akbar Khan Hill in Kabul, telling Shakeri of their difficult financial situation; others stand aimless after the Taliban came to power, paralysed and confused after being fighters since childhood.

© Hashem Shakeri

Evident throughout is Shakeri’s commitment to personalising his subjects. Staring into the Abyss offers a layered narrative, with each photo accompanied by a description of the subject’s personal story, sometimes accompanied by a quote from them. The images and captions are complemented by a timeline of events in Afghanistan, and a handwritten letter of personal stories by a group of girls who gather secretly to read and write. “What matters to me are the details of each individual – I don’t want them to become a series of interchangeable, uniform figures,” Shakeri explains. This combination of visual and narrative storytelling, building a fuller picture of the people whom Shakeri captures as individuals, not mere statistics of suffering, is a key tool in his mission to foster more empathy in accepting the what he terms ‘other’. “When audiences become familiar with the details of people’s lives and personalities, they no longer see them as distant, unfamiliar others. Instead, they recognise their shared humanity,” he notes.

The ethical complexities of photographing in such an environment are not lost on Shakeri, who places high importance on building trust with his subjects and “remaining vigilant to ensure that I never exploit anyone’s suffering”. The time invested is evidenced not least by the photographer’s very presence in intimate contexts, particularly with women and individuals flouting restrictions imposed by the Taliban. The complexities inherent in this exercise are only increased by the practical challenges that photographers face working under the Taliban, and by the regime’s own weaponisation of photography for its own ends. “The Taliban seem to have recognised the power of images,” Shakeri observes. In this context, where images are increasingly censored and the regime works tirelessly to control the narrative, Shakeri’s work stands as a defiant act of witness.

As I walk around the small gallery room, looking at images that at once feel a world away and yet are deeply relatable on a human level, I begin to contemplate what impact this witness might have here, on a rainy Bristol Thursday – particularly in an era of image overload. “In this hyper-connected age it is certainly not without impact, but can photography today truly reshape fundamental structures on a large scale? I’m not so sure,” Shakeri admits. He points, however, to the “ordinary mobile phone image” that captured Jina Amini’s death in a Tehran hospital, a snapshot that ignited a movement in Iran, as an example of photography’s profound effect. “If even one person is influenced by my work, that in itself is hopeful and rewarding,” he says. In this sense, Staring into the Abyss becomes not only a reflection on Afghanistan’s present, but also a reminder of the potential power of photography as a weapon of freedom.