Currently participating in the Sharjah Biennial, the researcher draws upon her family heritage to reflect on Tuareg nomadic experiences and the impact of mineral exploitation on the Sahara.

Canvas: Your research addresses what you describe as “nomadic imaginaries ” in contemporary Tuareg societies. Can you explain more about these and your other areas of interest?

Maïa Tellit Hawad: I examine the lasting inscriptions of global energy markets and nuclear infrastructures on Saharan bodies and landscapes. My research focuses on atomic tests in Ahaggar (present-day southern Algeria), uranium extractivism in the Aïr region (present-day northern Niger) and the regimes of exception – environmental, political and legal – that legitimise the capture of an ecosystem and its irreversible radioactive contamination. These lands, inhabited for centuries through nomadic and semi-nomadic modes of existence, have been increasingly reshaped since the 1960s by extractive infrastructures that impose new spatial, social and epistemic orders.

My research is also deeply personal. My paternal family is from the Aïr region, which in Tuareg geography is known as the south-eastern territory. I root my research in the experiences of Tuareg communities, exploring how they apprehend the present situation and negotiate the imposed enclosed horizons. I focus on these nomadic imaginaries and conceptions of land, particularly land that has been excavated, transformed and rendered toxic by mining infrastructures. What temporalities of disaster and dispossession do they trace? What vocabularies and expressions are mobilised to make sense of it? What does it mean to be a nomad in the twenty-first century on a fragmented and polluted terrain? What dreams and futures emerge from a land that has been so deeply wounded?

You lecture on the Environmental Architecture programme at the Royal College of Art in London and have worked on several short films alongside your own research practice. What approaches are most effective in terms of developing knowledge and awareness?

I need constellations of relationships and expressions in my practice. In the context of violence, political and epistemic asymmetry, how can other paths and voices be expressed? I don’t have a single answer or method, but I am drawn to practices that multiply perspectives, questions and modes of storytelling. I studied philosophy and I am now pursuing a PhD in a department oriented toward literature, but I engage closely with other disciplines, researchers and practitioners in anthropology, architecture and cinema. This allows me to reframe the questions I explore and the fields I navigate, which have historically played a major role in the marginalisation and erasure of the communities with whomI collaborate and conduct research.

What role does creative or cultural expression play in reexamining perspectives?

Until very recently, the academic world had remained largely silent on the topics of nuclear testing and uranium mining extractivism. It was poets, artists, filmmakers and architects who forced these issues into global debates. On another level, it is necessary to break away from the rigid conceptual, spatial and disciplinary boundaries that have structured discourses on ‘The Other’. Life and lived experiences always exceed the categories imposed by dominant scientific discourse. Cultural and creative expression can serve as differential lines of enquiry to reveal alternative geographies, circulations and relationships that rigid academic frameworks have enclosed or erased, or are simply not able to see and question.

Your father, Hawad, is a painter and poet known for his use of Zardazghanab or furigraphy. How has his work impacted your own practice?

Zardazghanab is a literary and graphic practice that uses words, letters, signs and strokes as munitions to face disaster and dispossession. It is an expression that graphically and poetically mobilises our language, Tamajaght (Tuareg), pushing it to its graphic and fictional limits. It is also an act of inscribing within the infinite space and time of imagination, within the dance of our alphabet, bringing new fields of possibility and subverting chaos by mimicking its vocabulary and extending it beyond its own logic. My father’s work weaves together a profusion of registers: Tuareg tales and Sufi fables, historical and multi-voiced poetic narratives, memories of mourning, domination and anti-colonial resistance, as well as satire and humorous storytelling.

I grew up within this relationship to language and the generative power of stories and imagination, but also with an intimacy and connection to his language, Tamazigh, an African language that remains largely minoritised. However, it persists in its existence and expression, not merely as a relic of the past but also as a force capable of conveying our worlds, our experiences and those yet to come. I was also profoundly shaped by the translation work of my mother, Hélène Claudot-Hawad, an anthropologist and linguist who exposed me to what it means to translate and publish a minoritised language in a globalised context and to find connections, equivalence, strategies of dissemination and publishing. In short, the politics of language.

How does your research overlap with the arts?

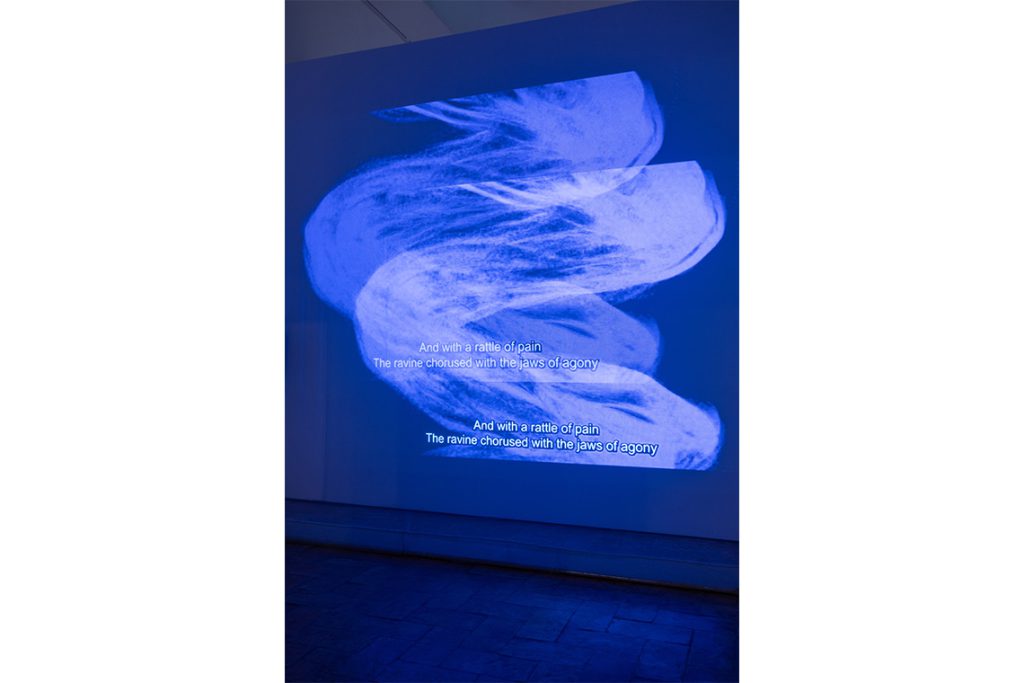

I work primarily through collaboration and encounter, often in friendship. In 2023, the Brazilian filmmaker and artist Ana Vaz invited me to write and read poetry and prose for her film and installation Meteoro, which she describes as “a sci-fi ethnography of different European capitals as axes of colonial thought”. The film traverses Paris like a hallucination, revealing what seems absent and contaminating beyond what we see: its colonial past and the potential disasters to come. I repurposed academic writings into narrative texts, blending them with poetry. We focused on the Saharan sand winds that, in a return to sender, sweep across Europe and its capitals, carrying with them the radioactivity to the heart of the former empire.

Similarly, last year, at the invitation of Caroline Courrioux (Villa Medicis), Valentin Noujaïm and I developed the first iteration of a research project Ilel (Le Mirage), an abstract video and multi-voiced fictional investigation based on the accidental flooding of the uranium mine site at Tagaza (Dasa) in the heart of Central Sahara (present-day Niger). The installation weaves an imaginary enquiry where ramifications extend far beyond the flood that temporarily halted the contested implantation of the mine. An assembly of forgotten witnesses takes form, offering dissident interpretations of the incident. The voices of local inhabitants intertwine with those of personified natural and supernatural entities. These include the invasive water, the fossil aquifer, the perforated earth, the uranium ore, spirits, ancestors and mythical figures such as the Tuareg neckless bull, Azger wer nela iri, an unyielding entity rebelling against gravity and the destruction wrought by men as they gut the Earth. We combined mutant maps, interviews, songs, poetry in Tuareg and fictional voices in French to construct a choral narrative that complexifies the official narratives of the event.

What are you showing at the 2025 Sharjah Biennial?

Ténelé, which means ‘threads’ in Tamajaght, is a collective project commissioned by Amal Khalaf and the first iteration takes shape at Sharjah Biennial (see page 160) through the production of two large indigo textile pieces. The project is co-signed by 47 Tuareg women from the Aïr region, whose names are inscribed in Tifinagh in the space, and draws from our memories – both local and diasporic – and from our present, one marked by territorial fragmentation and intensive mining extractivism. To evoke this reality and the enclosed horizons it imposes, Tuareg discourses often mobilise images of rupture – a torn weave, a cut cloth, the wounded fabric of a territory. This project takes that metaphor and language seriously, and in response to the capitalist and extractivist capture of the desert, we have sought to recite another topography of the territory, one that resists the maps drawn by engineers and colonial administrators.

We chose to work with the surfaces of blankets (tabarde) and saddlecloths (iselas), which are objects of nomadic daily life and women’s craft. These textiles, traditionally gifted to family members and cherished ones, are objects of care and protection against the elements and the shocks of movement. On the textiles we created – whether collective or individual works – memories of the land through embroidery, inscribing a lived territory onto each fabric. Interestingly, what emerges is not a static geography but a nomadic evocation of thousands of itineraries, routes of both extensive and hindered mobilities. The embroidered pistes, roads and paths trace movement and concrete places within the artists’ geography. For example, when a path zigzags or approaches another line, it signals an obstacle forcing a detour. One must turn, lean toward another – a stronger line for support (esaqamar) – and, once strength is regained, continue on one’s own route. That is why the lines converge, bend and then diverge. Ténelé is both an archive and a recitation of the land – a way to weave, stitch and patch together a disarticulated geography and collective memory.

I am inhabited by the questions of audiences in the production of knowledge and artistic works. For whom do we create? With whom can we expand the field of discussion and relation? By using different forms of expression and mobilising art, I hope that we can open up spaces for encounters and dialogue beyond the exclusive realms of the conference room, the private university classroom or expert discourse.

This interview first appeared in Canvas 117: The Maghreb Issue