Presenting two titans of art history on a clean slate, big ideas abound in this knock-out exhibition at Al Riwaq Gallery – a space large enough to do justice to the immensity of the artworks on display.

Donald Judd and Dan Flavin are widely credited as the ‘founding fathers of Minimalism’, two artists who redefined perceptions of light and space through their considered use of material. The 20th century was an era full of ‘–isms’, and Minimalism joined the Western canon of art history as a central pillar of Modernism in the 1960s. It shifted creative thought away from painting and sculpture, and paved the way for conceptual art to later depart entirely from materiality. As such, ironically for a style laser-focused on reduction and clarity, Minimalism has become such a loaded term that the expression of its original ideas is often obscured by a dense web of artistic references, hampered by its own conceptual baggage.

The major exhibition Dan Flavin | Donald Judd: Doha in Qatar, therefore, set out to show Minimalism in an original context, unshackling the two artists to whom the movement is indebted from the influence of their own legacies. Michael Govan, co-curator of the show and director of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), tells Canvas, “It was refreshing to stage the work of Judd and Flavin within a framework that isn’t interested in the typical story of modern art as evolutions of form. I don’t think anyone in Doha specifically cares about it being a response to Abstract Expressionism, or a whole other set of references. I wanted to strip it of all that history and just let it be in a new space. Examining these artists from a completely different worldview has resulted in finding commonalities with objects like Qatari ceramics, for example, which can be very minimalist objects.”

Born from the longstanding partnership between LACMA and Qatar Museums (QM), Dan Flavin | Donald Judd: Doha was the first presentation of these artists in the MENA region, and the largest ever outside the USA, taking full advantage of QM’s vast 3600m2 Al Riwaq white cube gallery space as one of the very few places worldwide that could host an exhibition of this breadth and scale. Some of Judd’s works seen in Doha had never before been exhibited as a group outside of his Chinati Foundation–the sprawling gallery space that he built specifically in Marfa, Texas, to house his largest installations– simply because they couldn’t have fitted anywhere else.

Inside the gallery, the show was arranged like a Venn diagram, with half the rooms dedicated to Flavin and the other half to Judd, with three rooms of overlap in the centre. As Sheikha Al Jazi Al Thani, head of exhibitions design at QM, explains, “The layout of the exhibition allowed the audience ample room to experience the distinct characteristics of Judd and Flavin’s work. The format not only accentuated the individuality of each artist’s contributions, but also enabled us to highlight specific series, such as Judd’s plywood series, in a comprehensive manner.”

In a sense, the exhibition’s distinct-but-connected template mirrored the relationship between the two artists. Their friendship was obvious, with Judd even naming his second son after Flavin, but their bond was more familial than professional. It is tempting to see them through a rose-tinted historical lens as a double act, Judd the straight man and Flavin his foil, but this would be a disservice to their highly individual paths through life. Govan was personally very close to both artists, and reminisces that “There was a great love affair between these two giant intellectual figures, but in a sense they grew apart from each other. This show is their first joint presentation in over 20 years, so we were able to bring them back together and see where their careers had gone.” The exhibition’s curation therefore mutually reinforced the different choices each artist made in exploring the same themes: colour, material, systems, simplicity.

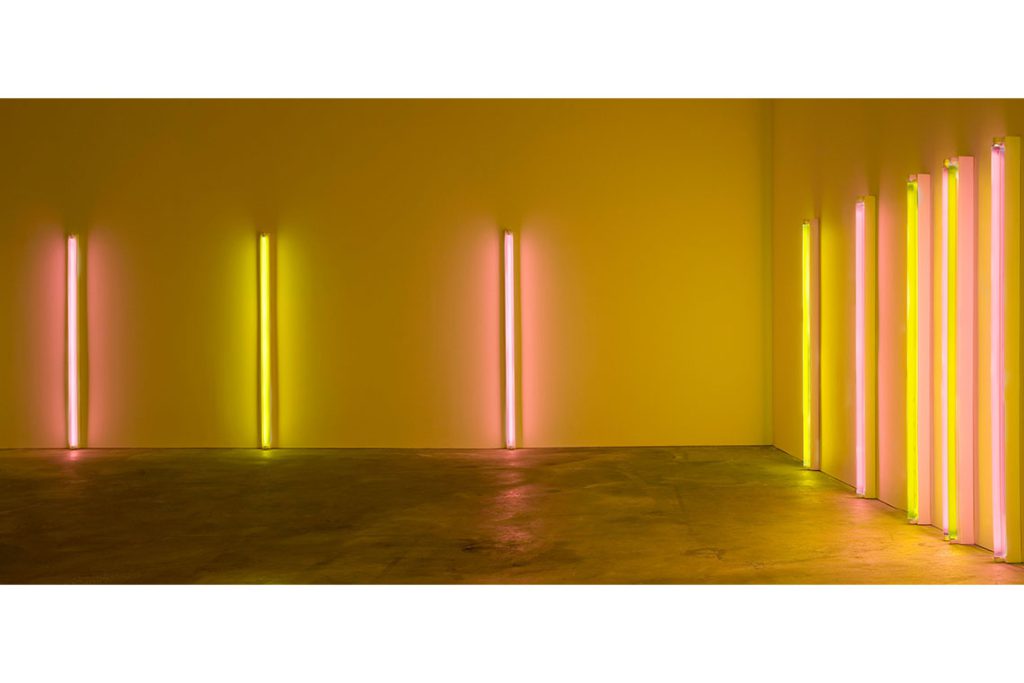

Walking from room to room, the push and pull of their two personalities was palpable. Flavin’s use of light and colour has immediate charisma, affecting its environment so potently that Govan admits it can make it impossible to stage him alongside other artists, as he “takes them over”. This was evident in the central room, where Flavin’s Untitled (to Don Judd, colorist) 1-5 (1987) stood along a wall opposite Judd’s aluminium Untitled (1991). It was a beautiful pairing around which the whole show revolved, and demonstrated the active/passive relationship between the pieces. The planes and hemispherical tubes of aluminium were cast in a rainbow iridescence from the coloured lights, covering the metal like a skin; where Judd provided all the substance, Flavin basked in the limelight.

The expansive white walls and floor of the gallery augmented Flavin’s installations no end, absorbing and reflecting uninterrupted planes of colour, and through tall open doorways you were able to see which colours were coming up next well before you entered a room. Judd’s works, in contrast, materialised space around them, and in doing so generated a conceptual mass. Mass creates gravity, which explains why you were drawn towards them, moving through his rooms as if in orbit around one major installation after another.

Presented in apposition to each other, it became apparent that Flavin’s work comes to you; Judd’s makes you come to it. Flavin takes over environments, conquering everything his light touches in primary hues of red, yellow and blue, whereas Judd’s collection of immovable objects assimilate and withstand anything that might enter their presence.

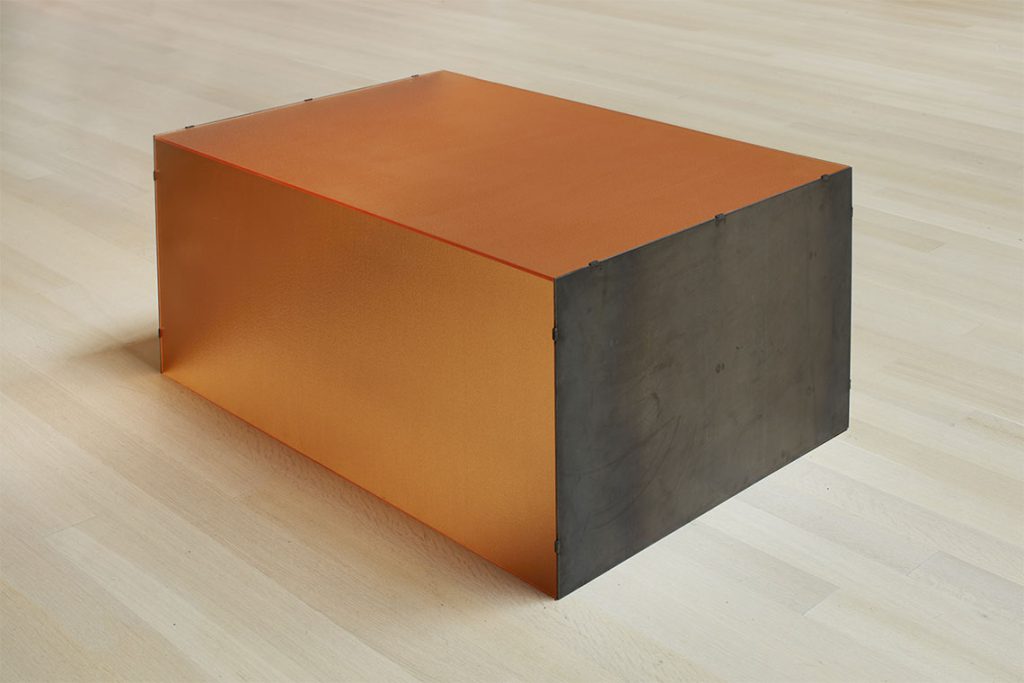

Govan continues: “We imagine their dialogue as young artists must have been intense conversations about reducing form towards Minimalism. But, in fact, colour was what they most admired about each other’s work. Judd wrote about Flavin’s use of colour; he was obsessed with the way colour and light can enter a space and come back out, and even the colouristic qualities of galvanised metals or plywood.” An example of Judd’s consideration of material and colour was shown in a plexiglass cuboid that stood on the floor in an early room. The semi-transparent material emitted a warm orange glow as light from the overhead spotlights passed through it, illuminating its interior/exterior boundary.

Judd, who started his career as an art critic and remained deeply philosophically engaged with art all his life, starts his 1993 essay Some Aspects of Color in General and Red and Black in Particular, “Material, space and colour are the main aspects of visual art. Everyone knows that there is material that can be picked up and sold, but no one sees space and colour. Two of the main aspects of art are invisible; the basic nature of art is invisible.” This show rendered the invisible not only visible but practically tangible, as shown by one room filled with a series of six plywood 2.5 m2 cubes, each with one side open. Face to face with a volume large enough to comfortably swallow you, the sudden awareness of their interiors was profound. Judd, who took nothing for granted, understood that space must be actively created if it is to hold impact. Through little more than demarcating the volume occupied by these cubes, and repeating the effect in a long line of modulated space, he enlivens the liminal voids between material. Never has plywood felt more electric.

Flavin too is a master of materialising atmosphere. He lived on the Hudson River and had built a quality collection of artworks from the Hudson River School. Like most romantics, and Flavin certainly was, he was a man out of time, and was motivated to transplant the sense of light those paintings captured into his own contemporary context. Exemplary of this was his alternating pink and ‘gold’ (1967), which filled the largest room dedicated to him. Pink and golden fluorescent tubes radiated out from the centre of each wall at increasing intervals. The catalogue listed the work’s dimensions as “variable”, as the precise size of this installation is always dictated by the size of the room. This was the largest iteration of the piece ever staged, and its impact was correspondingly impressive. Approaching a sense of the sublime similar to that which Flavin would have encountered on the banks of the Hudson, the colours reverberated around the full width of the room, tending towards the infinite.

Experiencing artworks of this magnitude, one can understand why both artists rejected the label ‘minimalist’. It gives audiences a simple means of pigeonholing them, and fails to capture the immensity of the themes they were grappling with. Govan sums up the show, saying, “The point was to see how something cataclysmic can come from dialogue. Immersed in this complex thing, which is anything but minimal, your eyes are overloaded with colour and flavour. These two artists found a way of translating the most minimal means into the maximum effect.”

Maximalism is a far more appropriate term for what these two artists have truly instigated, but it would perhaps be hard to understand this if not for the scale of the exhibition, which gave both artists ample room to spread and flex their wings. If they had seen the show themselves, Judd and Flavin might have shared a knowing smile; they often joked they could never find gallery spaces large enough to accurately convey the ambition of their ideas. In this instance, thanks to the opportunity afforded by QM’s sensational facilities, a maximal effect was achieved. The exhibition won’t be touring anywhere else in the world; how could it? Only in Doha can this once-in-a-lifetime show be experienced.