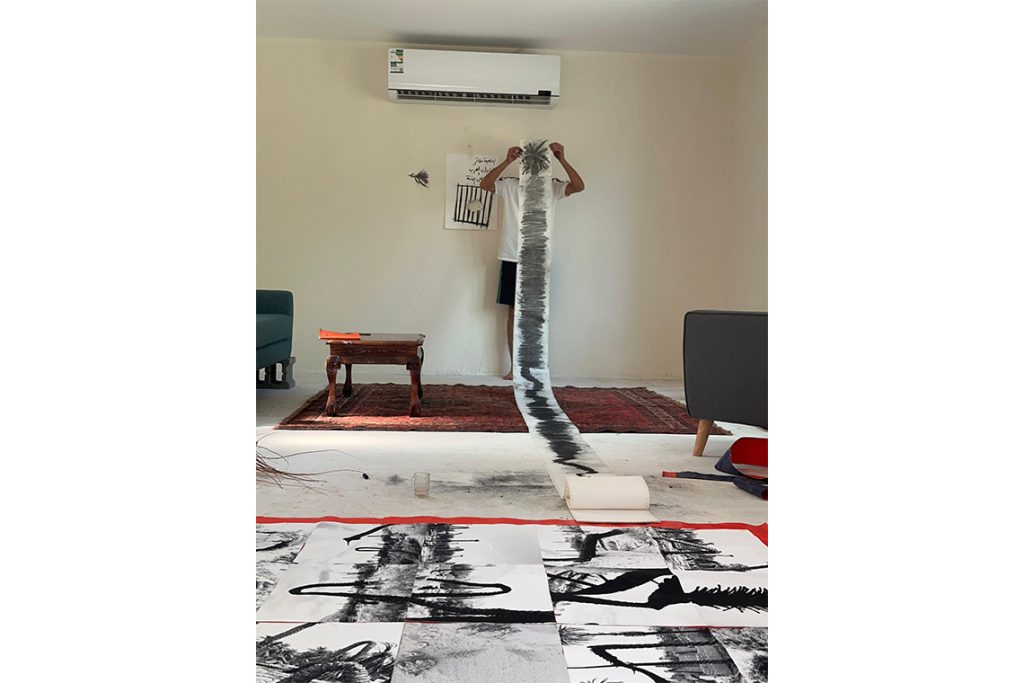

The artist assembles memory in the oasis as he seeks to investigate the real value of what is left behind.

In the oasis city of Al-Ahsa, where date palms rise from desert springs and life depends on water flowing through ancient channels, Mohammad Alfaraj moves through the landscape asa collector of traces. His hands gather what others might overlook: discarded palm fronds, weathered doors from demolished homes, the dried heel of a palm branch that locals use for cooking but in which he sees a bone. “I’m an assembler,” he explains in a recent documentary. “I like to tie things together, and shape them in a specific and different way.”

This impulse to assemble and reconfigure defines Alfaraj’s multidisciplinary practice, which spans photography, film, sculpture, installation and writing. But unlike many contemporary artists who work across different media, Alfaraj’s expansive approach emerges not from academic training but from a deeply rooted connection to place and an insistence on bearing witness to what is at risk of disappearing. His first institutional solo exhibition, Seas are sweet, fish tears are salty, now showing at Jameel Arts Centre in Dubai, crystallises a practice devoted to reading and recording the mutual inscription of human and non-human worlds upon one another.

Al-Ahsa itself embodies contradiction – a fertile, agricultural landscape that simultaneously houses Saudi Arabia’s largest oil reserves and has helped fuel the country’s industrialisation. This tension between preservation and extraction, between sustaining life and accelerating progress, permeates Alfaraj’s work. The oasis exists as a pocket of possibility in an otherwise inhospitable landscape, a place where human survival depends entirely on natural systems. “I grew up and lived here in Al-Ahsa, always hearing and learning how important and respected the natural world and environment are, respecting the palm tree as it is the source of life,” Alfaraj reflects. “All of that is making me truly believe with time that there is no I and the other, there is only us, and that the traces we leave on others are the traces we leave on ourselves.”

His materials arrive already freighted with history. The palm tree, ubiquitous in Al-Ahsa’s landscape and central to its economy and culture, appears throughout his practice in various states of transformation. Fossils of Knowledge (2019–25), installed in the outdoor courtyard of Jameel Arts Centre, assembles dried palm bark into a skeletal form that suggests the remains of some ancient creature. The work operates simultaneously as monument and warning: what happens when the knowledge embedded in these trees – economic, political, societal – faces oblivion? The installation becomes a plea from the palm tree itself not to be forgotten.

The artist’s particular genius lies in perceiving these materials as what he calls “memory capsules”, objects that carry within them the accumulated traces of their use and meaning. In his vision, the alkaab – the heel of a palm branch – becomes a spine, a ribcage, a fossil that speaks to the mixture between humanity and nature. Yet Alfaraj insists this transformation is not solely his doing. Through working with participants in a recent palm-weaving residency, he discovered that “originality also comes from the materials themselves, they kind of lead you more than you lead them.” This seeing otherwise, this ability to read new truths in familiar forms, extends across his practice. Tree stumps become bones, withered fronds transform into a bird’s wings, and traditional irrigation channels suggest the vertebrae of vast, forgotten creatures.

Photography forms the foundation of Alfaraj’s practice, serving as his primary tool for connection and exploration. His ongoing film Glimpses of Now (2015–present) compiles mobile phone and handheld camera footage gathered over a decade: girls dancing by the shore, camels crossing the desert, the call to prayer echoing through narrow streets. These fragments accumulate into what might be understood as a collective portrait of a moment, an archipelago of the everyday in a period of accelerated transformation.

Alfaraj refuses to stop at documentation, however. His photographs and films become raw material for further assembly. In Fossils of Time: Al Ahsa Water Veins (2025), he layers images at different heights and scales, creating spatial collages that collapse distinctions between past and present, human and animal, built and natural. “The picture is a fossil of time,” he asserted in the Jameel documentary, extending the metaphor beyond the photographic to encompass his entire practice as a kind of excavation and act of preservation.

Writing, too, serves as essential technology in this project, making the world easier to understand whilst lending it humour and hope. His exhibition takes its title from one of his own poems, and throughout the show, narratives multiply and interweave.

In the film Don’t Touch My Tomato! (2025), a farmer and a bird quarrel over rights to a tomato plant, each certain of their claim – until the tomato itself speaks up, declaring that no one asked how it felt. The drama springs directly from observation. “Living around an agricultural community made me see and feel its theatricality,” Alfaraj tells Canvas. “The farmers love birds and depend on them as part of an ecosystem, but they also hate them sometimes for eating the plants and seeds. It’s contradictory and dramatic, and inspires me to write these short stories or make works around that with drama, humour and life.” These fables, at once playful and pointed, insist on the subjectivity of non-human actors, on the validity of perspectives beyond the purely human.

This commitment to multispecies storytelling reflects an ethical stance as much as an aesthetic one. Love is to Leave the Door to Your Garden Ajar (2025) constructs a gathering space from salvaged doors – real doors from real homes in Al-Ahsa – that somehow remains open, even as it encloses. The work suggests both the vulnerability and the generosity required to live in genuine relation with others, human and otherwise. Meanwhile, A Phone Call from the Heavens (2025) strings together discarded food cans, transforming the makeshift telephones of children’s games into instruments for prayer, for calling out to what exceeds us. Alfaraj maintains the experimental rush of childhood, a freedom he attributes partly to his lack of formal art training. This gratitude for a lack of predetermined constraint allows him to follow materials and stories where they lead, to assemble without fixed outcomes. Yet there is nothing naïve about his approach. His work acknowledges complexity and contradiction whilst maintaining what he describes as a “sense of hope”.

In an era of ecological crisis and accelerating loss, Alfaraj’s practice offers neither nostalgia nor despair. Instead, he proposes a different relationship to the very act of making. “I believe we are not supposed to make anything anymore,” he suggests – a provocative statement from someone who continues to create prolifically. Perhaps what he means is that we should stop imposing and start listening, stop extracting and start assembling with care, attending to the traces already inscribed in the materials and landscapes around us. When asked how he balances acknowledging damage with making space for hope, his response is generous: “Life is filled with those scars, and living it is about finding those little spaces in-between, enjoying the fact that those scars close, stitch and heal, and realising how powerful and incredible is that ability in us, something that we won’t know about if we are not scared in the first place.”

In the oasis, survival has always depended on reading signs correctly, on understanding that human life remains inseparable from the life of water, earth and palm. Alfaraj’s work insists that this knowledge, far from obsolete, may be precisely what we need to carry forward – not as preservation of the past, but as a practice of attention, of reciprocity, of learning to be led by the materials and landscapes that sustain us.