Basel Social Club returns for 2025, taking over a former private bank, cementing its place as the unconventional breakthrough star initiative during art week in Basel, creating an inclusive space for artistic exchange.

Every June, Basel becomes an art world epicentre. Think polished booths, seven-figure price tags and enough air kisses to start a windstorm. Yet a few blocks away, something cool is brewing. Now in its fourth year, Basel Social Club avoids the average white-cube affair. It’s looser, bolder and delightfully off-script, with free entrance – everything that an art fair isn’t. The conversation always goes: “Have you been to the Social Club?” “Yes! The queue was long…”

At Rittergasse 25 in Grossbasel more than 100 rooms of a former private bank – built to hoard money and keep secrets – have been flung open to the public for the first time. Curated by Olamiju Fajemisin, CLEARING’s director of programmes, this year’s theme draws inspiration from the language of finance: its value, exchange and trade. Turning what used to symbolise wealth into a platform for generosity, it offers ideas, rituals, stories and fresh takes on what worth means.

Men in suits and ties stand guard at the door. Staff wear “Burn galleries not calories” T-shirts in collaboration with Misc Pippa, as they welcome guests amid the former bank’s grandeur. Money talks, and it’s everywhere – take Sturtevant’s Shifting Mental Structures (Millionaire/Money) and The Greening of America (both 2000) sprawled across the floor as a welcome gesture. Kwan Sheung Chi’s videos of counting millions in euros, dollars and liras appears in corners. Playfully, money shows a funny face in Sergej Jensen’s Untitled (Money Face) (2006). Neon-lit phrases become gentle notes throughout. Jenny Holzer’s White People Curve serves as a reminder that “Abuse of power comes as no surprise” and we are exhorted to “enjoy diversity” in Divya Mehra’s Without You I’m Nothing (Eating the Other) (2025).

Performances take place simultaneously, and there is almost no way of telling what is and isn’t art. When I visited, a person covered in black fabric was eerily crawling down the stairs, while another impatiently waited for the toilet. On another floor, a person was posing for a selfie stick while holding a vacuum cleaner, while someone else wearing the same outfit was chit-chatting with possible collectors. In the courtyard, Dahoon Nam handed out balloon dogs on paper plates as part of his durational performance Jeff Koons SPECIAL SALE. In Abdu’Allah’s LIVE SALON, artist Faisal Abdu’Allah became a barber while talking to his client, with everyone else allowed to listen. The lines were perpetually blurred, and I was into it.

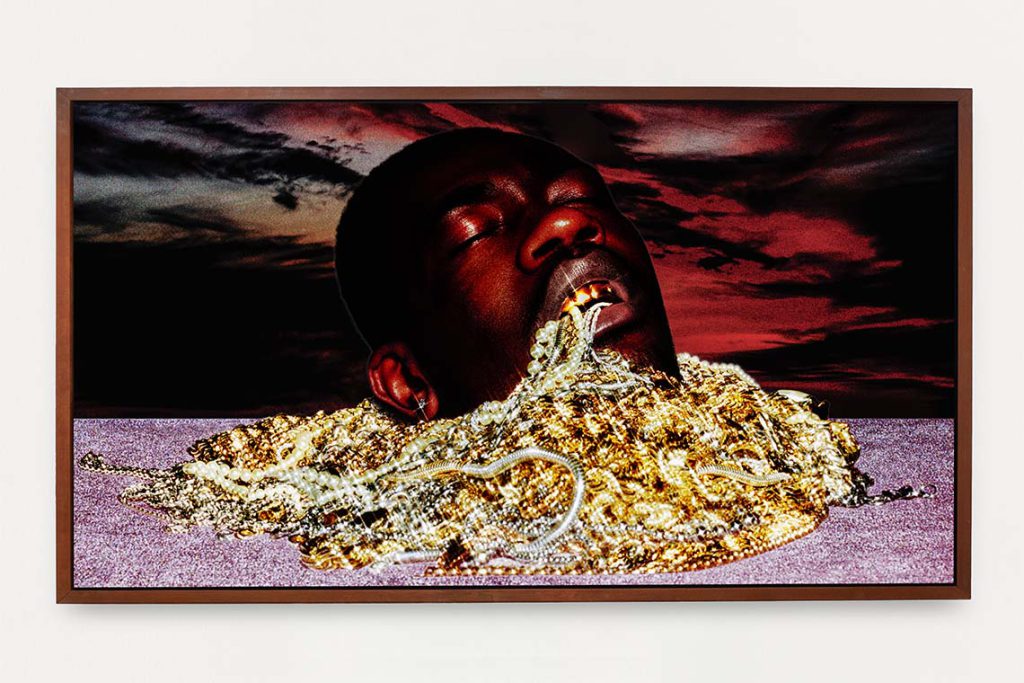

While it was refreshing to see photographs by Nan Goldin and Wolfgang Tillmans, and emerging talents like Ian Waelder and Jiyoon Chung, it was a definite pleasure to be engulfed by Pol Taburet’s Home Sweet Jo II (2024). Presented by Mendes Wood DM, Taburet’s 300 cm x 500 cm image reminded me of excess and exhaustion – eyes closed in a non-restful way, as gold jewellery came out of the subject’s slightly open mouth.

I was eager to see the showcase of Arab Bank Switzerland’s collection – curated by Nina Roehrs, with works by big-shot artists such as Damien Hirst, Kevin Abosch, Sarah Meyohas and Jonas Lund – but left unimpressed.

In a quiet room above a leather sofa is an intriguing story of Beirut’s golden haze during the Swinging Sixties and Super Seventies. It is Raed Yassin’s Sex, Spies and the Suicide Dancer (2017), showing covers of Alf Layla wa Layla, an erotic magazine meant to promote nightclub dancers but which unravelled into a honey-trap operation so potent that it seduced royalty, scandalised a nation and vanished its stars in a trail of whispered disappearances and dark glamour.

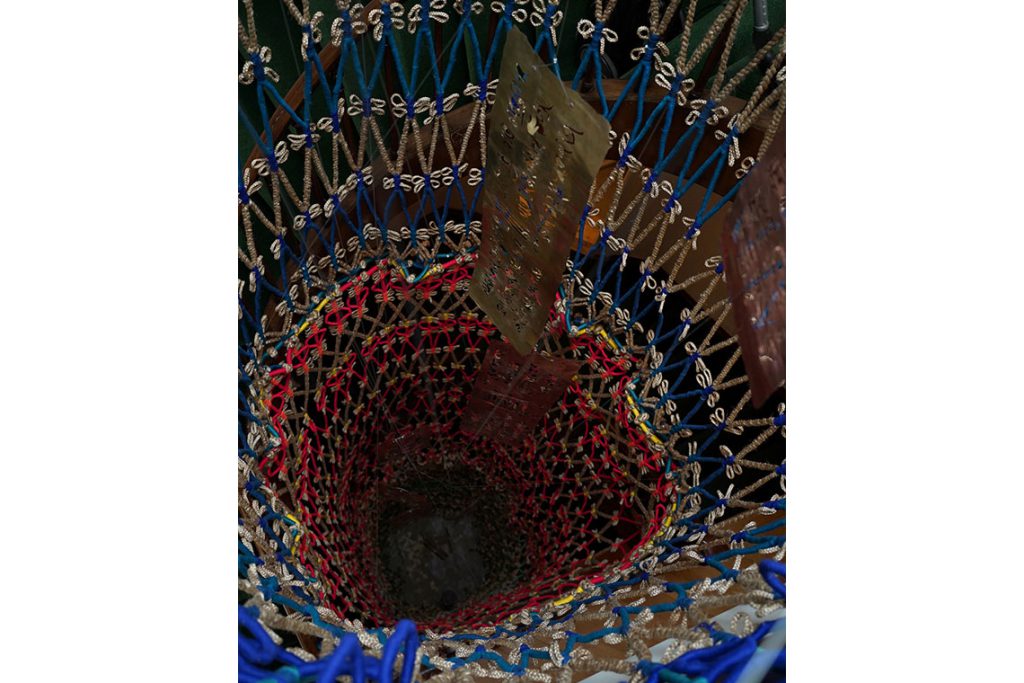

It is impossible to ignore Pathraj Chronicles (2023) by Kamruzzaman Shadhin – an installation of jute, brass and copper woven to memorialize a traditional Bangladeshi craft into a lyrical archive of disappearing lives and voices.

The last few rooms on the top floor show beautiful yet explicit imagery. Male depictions of perverse yearning can be seen in the graceful strokes of Sadao Hasegawa’s drawings and Billy Coulthurst’s suggestive paintings, but it is in Krzysztof Jung’s intimate portraits from the 1970s and 80s that another form of yearning is portrayed – that of intimacy.

At Basel Social Club, I was overwhelmed and underwhelmed at the same time, as it became harder to focus on good or bad art. Everything is happening all at once. The vibe is buzzing with all things happy, and the pressure of selling artworks is faintly present. The insurmountable display of wealth in a Swiss bank triggers suspicions of curatorial cop-out and redundancy. However, in digression, it is also a smart and humorous way to remind the audience of money that they have or don’t have, and which they despise or aspire to.

Basel Social Club 2025 runs until 21 June