In search of the darker truths lurking beneath the surface of society, the artist uses her multidisciplinary practice to materialise the overlooked, or even deliberately obscured, narratives in life.

“My concern about invisibility and the matter of the invisible is as old as I can remember working in art,” says Nadia Kaabi-Linke. “I have always been drawn by what is not being said but is present nonetheless, be it taboos, shameful stories, uncomfortable pasts, hidden crimes.” Employing a broad range of media, Kaabi-Linke works to bring these concealed truths – which exert power from behind a camouflage of purposefully obscured narratives, shame or truisms – into the light, rendering them palpable, indeed unignorable, by their physical form.

Kaabi-Linke, born in 1978 to a Tunisian father and Ukrainian mother and growing up between Tunis, Kyiv and Dubai, believes the desire to render visible that which usually flies under the radar may have to do with her origins. “Coming from both Tunisia and Ukraine, my ancestors got used to the strong influences of oppressive and dictatorial regimes,” says the Berlin-based artist, opening up to Canvas about the “unexpressed contraband” that seemed to underlie everything from conversations to urban legends and jokes.

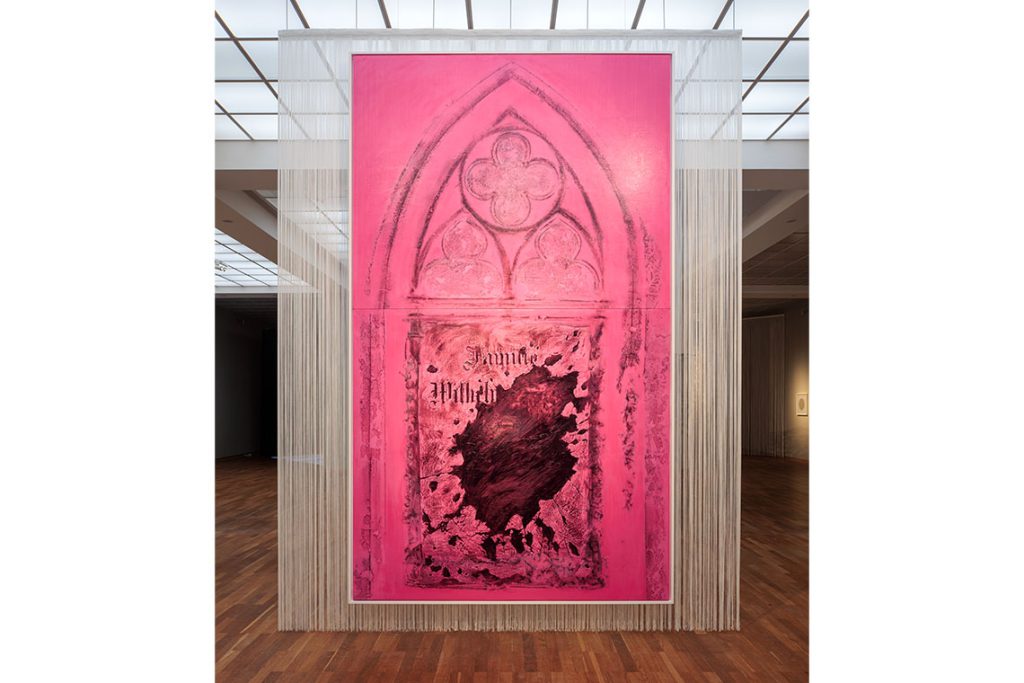

As Kaabi-Linke’s practice spans painting, sculpture and installation, so too it engages with diverse themes and contexts: from the erasure of Ukrainian culture during Stalin’s Great Purge in the 1930s, as is the focus of her 2023–24 show Seeing Without Light at Hamburger Bahnhof, to her 2018 sculpture Jins Al Latif (The Fairer Sex), which she says “talks about the invisible power and strength of Arab women within their societies”.

Migration and immigration have been, though, particularly central themes to Kaabi-Linke’s work – not least because they are pertinent to her life story. While her two-channel video installation No (shown at the 2012 Liverpool Biennial) draws on her own experience of the arduous UK visa application process, her performance and installation Walk the Line (2015), for example, saw volunteers walk between two poles, wrapping them with thread calculated to be the length of the Texas-Mexico border. The result was a symbolic, but nonetheless dense, border wall.

Even when dealing with questions of migration – a theme that evokes movement and transience, rather than a sense of rootedness – Kaabi-Linke’s approach, as she describes it, is “often site-specific and based on given materials”. One such project, Meinstein (2011–14), stands as a permanent public artwork in Berlin’s Neukölln borough, which is characterised by a large immigrant population. Thousands of stones were imported from the homelands of Neukölln residents and placed in a mosaic-like formation across a public square according to data collected during community workshops. As its name, meaning “Mystone”, hints, the project inscribed the borough’s inhabitants, and their diverse origins, into the physicality of the cityscape.

at Hamburger Bahnhof – National Gallery of Contemporary Art, Berlin, 2023. Photography by Jacopo La Forgia. Image courtesy of the artist

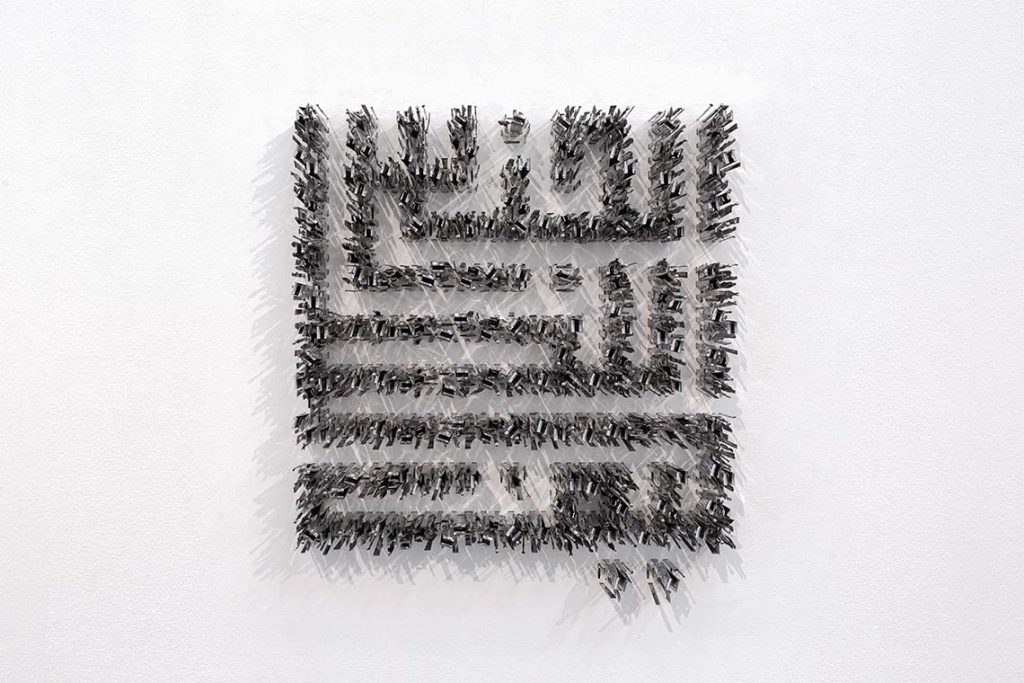

Perhaps Kaabi-Linke’s most well-known work, Flying Carpets (2011), cast the movements of immigrant street vendors on a Venice bridge – who would lay out their wares on sheets or rugs, in order to swiftly gather them up again in case of a police visit – in stainless steel, suspended from the ceiling like hovering metal cages. The work, shown at the 2011 Venice Biennale, lends permanence to a feature of Venice city life that is (often wilfully) overlooked, while challenging the notion of the flying carpet as a magical means of escape in Orientalist fantasy. Rather than symbolising freedom, these flying carpets speak of confinement, and even imprisonment.

Flying Carpets exemplifies a technique, dubbed “a grammar of things” by Kaabi-Linke, which is common to many of her works. “I like to combine objects and signs in contradictory ways to bring new light to problematic topics and offer an alternative view of reality or what the collective seems to perceive as truth,” she explains. Sometimes this means instrumentalising the tools – the very “grammar” – of violence that the artist seeks to expose. In her 2023 work Disarmed Metaphysical Objects, a co-production with shaman Vamarie Nanej, Kaabi-Linke works with ceremonial “metaphysical” objects, used within the phenomenon of black magic in North Africa, in order to break them down and dysfunctionalise them. “Bringing this deep, dark, invisible and frightening phenomenon into the visible helps to disarm them,” says Kaabi-Linke. “It makes the arcane knowledge behind them transparent.”

Image courtesy of the artist

In spite of often “starting site-specifically with a localised problem”, it’s important to Kaabi-Linke that her work be universal. “It has always been about the humanity that we all share,” she explains. “It is important to me that my art can touch and talk to anyone.” This commitment has seen the artist foster a practice that is accessible and inclusive, including making Seeing Without Light accessible to visitors who are visually impaired. “I made sure that those who cannot see with their eyes can perceive the works with their fingers and ears,” she says. “We have invited the Fragmentation Orchestra, who work with real time improvisation, to produce a music piece for each artwork in the show.”

For Kaabi-Linke, bringing unseen realities to light is an artistic imperative, not least because of their potential power when left unnoticed, unchecked. “The invisible violence, present or past, is active even if we don’t see it or decide to look away from it,” she posits, “but like the unconscious, sooner or later the covered truth will come up to the surface and be acted out while controlling us simultaneously.”

Photography by Timo Kaabi-Linke. Image courtesy of the artist

On this front, the current state of global affairs – notably the wars in Gaza and Ukraine – represents to the artist both something of a shift and a tragic inevitability. “Sometimes, I wonder if this [deep trauma coming to the surface] is what we can now see in the most dramatic ways in the Middle East and Eastern Europe. In both cases, aggressions are carried out by profoundly traumatised people,” she considers. Kaabi-Linke’s practice has largely explored subliminal violence; she notes, however, that as “violence is not that imperceptible anymore” and rises to the surface, other realities are forced into the shadows. “Acts of violence pop up on our screens with high frequency,” she reflects. “Compassion, support, care and healing are still happening, yet we don’t see much of it when we turn on our devices.”

For the artist, it is all – the trauma, the violence, the care and the solidarity – worth unearthing. “Digging into the darkness is an opportunity to unearth the truth and find some light among the shadows,” Kaabi-Linke reveals. “This is probably why many of my works unfold a dialogue or dance of light and shadow.”

She is, nonetheless, humble – if not healthily sceptical – about the potential impact of her art. “In my opinion, art is not a tool to change the world,” she readily affirms. Instead, just as she describes how the revolutions in 2011 in Tunisia and 2014 in Ukraine opened the doors to “talk freely about everything”, so she hopes her work catalyses mini personal revolutions of awareness and responsibility. “It does not work as directly as launching a statement on something and telling people how to live and what needs to change in society,” Kaabi-Linke explains. “It’s more an intimate process where the work talks to one’s heart. If my art can trigger these individual changes, that’s worth making art for.”