Leading a life of persistence and independence, the artist champions personal themes of the female soul and the natural scenery of her native homeland.

Chatting with the experienced Emirati artist Najat Makki feels like hearing the stories about one’s cool aunt: the one who unconventionally travelled abroad, obtained a doctorate in art and ultimately lived independently, acting as the leading lady of her own life. As soon as I address her as Dr Najat at the beginning of our conversation for Canvas, she hastens to interject. “No, no, no. I don’t like it when people call me ‘Doctor’. I understand why they would do that in the academic world, but between us artists and intellectuals, it’s just Najat,” she says warmly in her soft-toned voice.

Makki, who was born in the historical district of Dubai prior to the unification of the United Arab Emirates in 1971, is a woman of another time. Living a simple yet vibrant life, she grew up near the turquoise waters of Dubai Creek, a natural view of historical significance that offered her great inspiration. “Through the beautiful creek’s waves and colours, we were transported from one bank to another,” she recalls. “Every day the water had a different colour and people’s faces were reflected on the surface of the water. It was all a poetic scene.”

She also recalls the busy atmosphere, where a specific “tempo” played (both visually and sonically) across old Dubai’s markets, bakeries, gold and fabric shops manned by multicultural workers who spoke a variety of languages. “From the moment I opened my eyes, I saw and felt a sense of movement in Dubai,” Makki says. From an early age, she was sensitive to her surroundings through all her five senses. Her father was a tradesman in herbal medicine and it was through his practice that she developed innate senses of touch and sight, able to distinguish between the melange of different herb textures and colours. “This palette was always present in my mind as a child,” she recalls.

At home, little Makki would draw with charcoal on the walls and her variety of animals and pets, from chickens to parrots, enhanced her sense of absorbing colour. Drawing did not stop at home, as she literally continued on the streets of local neighbourhoods with her male and female friends. “At the time, there was no difference between a girl and a boy at all. We always used to play together,” she recalls. It was her father who noticed her love of drawing and started providing her with pastels and colouring pencils. “Thankfully my family encouraged me, unlike others who didn’t want their children to pursue art,” she says. “I was lucky that my family members were understanding and tried to help me.”

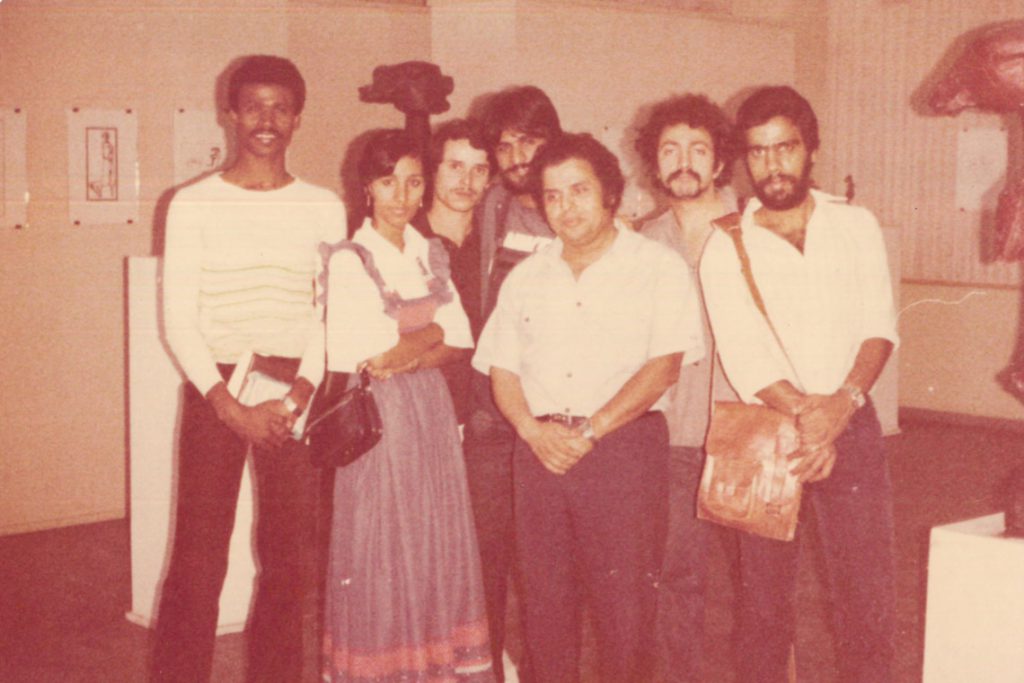

Despite her limited access to culture at the time, she still saw art as her future, working hard to make it happen. During the late 1970s and early 80s, Makki – along with some of her classmates – travelled to Cairo to study art, which was an unusual move at the time for a young girl from the conservative Gulf. “My parents insisted that I should study in the UAE. There was this idea of, ‘How could a woman leave her country?’ There were social constraints against women,” she says. “My parents eventually found out that in Egypt we would be in safe hands, thanks to the UAE embassy and the student accommodation. My father was worried that I might become an exile, but I insisted… It wasn’t easy. Even if my parents approved, society back then wasn’t truly aware of the role that art played.”

During her years in the Egyptian capital, famed for its rich architectural landscape, renowned universities and museums full of antiquities, Makki encountered an open society and the history of various Egyptian civilisations, as well as mixed classrooms – all of which were new experiences for her. “I was shy, but not afraid”, she says of her days there. At the Helwan them was Athena, the Greek goddess of warfare, depicted historically as armed with weaponry and wearing a helmet or a wreath decorated with olives.

Looking at her other serene and heavily marked images, such as Conversations #1 (2023) and Resonance #4 (2023), I see how Makki builds layer upon layer of paint on her canvases, as if creating an abstract, almost kinetic, composition of waves, winds or homes. “Nature is very important, especially now,” she says. “The whole world is heading in the direction of caring more for the planet. We are part of this ecosystem. If we want to live, we have to preserve the environment.” Through her art, she is paying tribute to Bedouin heritage and emphasising the need to preserve the natural environment (sometimes using raw materials, such as sand), from the dunes of the desert to the waters of the creek of her native Dubai in a time of rapid modernisation.

After hearing lively anecdotes of Makki’s life, about which she reminisced in her Dubai studio, I couldn’t help but ask her if she had ever settled down in her personal life. “No. If I were married, you wouldn’t be seeing me,” she says with a laugh. Is it truly possible for a woman to be an artist, a wife and a mother all at once, I mused. “Raising a family and having a husband is a responsibility,” she responds. “I feel that any woman won’t be able to give herself completely to her art if she has a family. I had time on my hands and it was all a matter of fate. I don’t have regrets, because I have achieved many things in my life, but they didn’t come easily. I believe that behind every successful artist, many sacrifices have had to be made.”