The nations of the Middle East are slowly coming to the fore at a Venice Biennale of Architecture which is turning its focus away from traditional nations of the Global North. Canvas discovers ideas and imaginings from delicate strategies to work with landscape, right through to altogether more traditional mega-projects.

For an event considered the watermark of forward-thinking culture, the Venice Biennale can be slow to progress. Over the history of alternating art and architecture biennales, non-Western voices have not always been given an adequate platform. This imbalance is gradually changing, both in terms of curatorial approach and the desire of nations from the Global South in particular to reposition and rebrand themselves on the world stage. It seems timely, therefore, that the theme of the 2023 Architecture Biennale is The Laboratory of the Future. Led by Ghanaian-Scottish architect Lesley Loko, it focuses on African and diasporic voices, designers and vernaculars.

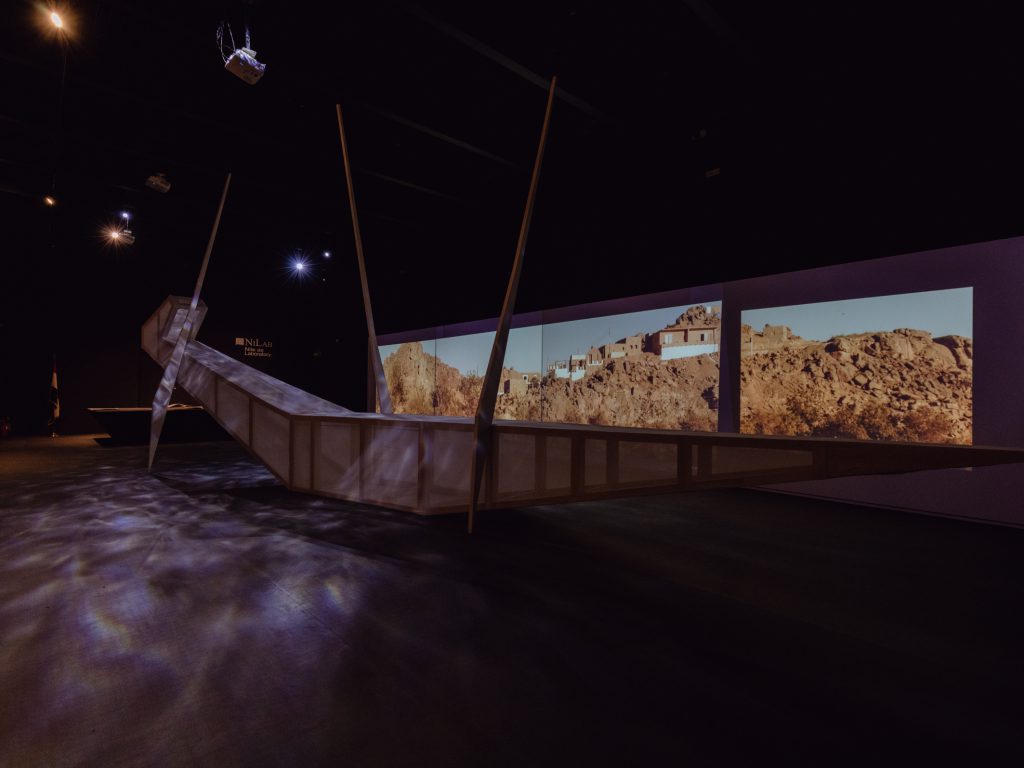

The only African nation with a pavilion in the historic Giardini site is Egypt, which took up its space in 1951 after the fall of King Farouk. Here it presents NiLab, an immersive reconsideration of developments along the Nile, focusing on local nature, culture, and landscapes. Landscape architecture and approaches to nature have become increasingly central to an Architecture Biennale which has moved from pure representation of architectural projects towards research and conceptual representation. This shift aligns with heightened global awareness of climate breakdown, though there is often a dialectic between nations projecting ideas of physical, cultural and economic growth while still wanting to present an image of helping fight the impact of the Anthropocene.

This dichotomy is evident in the Kingdom of Bahrain’s presentation, Sweating Assets, a vast landscape model supplanted with water channels that feed pools and planting. The water emerges from a giant glass vitrine, representative of the kingdom’s buildings and their air-conditioning systems, suggesting how sweated moisture could be collected to nurture an ecology. The wall text states that 74 million cubic metres of water from the island’s air-conditioning units could comfortably feed 2.8 million local date palms – a techno-utopian proposition which could easily be interpreted as apologism for reliance upon artificial cooling at a time when many designers are looking to vernacular rather than engineered solutions.

For the United Arab Emirates, Faysal Tabbarah’s Aridly Abundant does just this, with the architect questioning the presumption that desert landscapes are places of scarcity. His provocation offers a model of salvaging local rocks and materials to construct traditional dry-wall systems, supported by the 3D scanning of every component to support a construction process that fuses algorithm and craftsmanship. Tabbarah calls the outcomes “misfit assemblages”, and his UAE space is full of ad-hoc furniture and a large wall formed of this method of building.

The Uzbekistan pavilion also has walls, constructed by Studio KO who worked with students and master ceramicist Abdulvahid Bukhoriy to celebrate vernacular craftsmanship. Using locally salvaged bricks, an atmospheric labyrinthine structure has been constructed within the darkened room, illuminated punctuations highlighting beautiful, glazed terracotta fragments formed of traditional processes. At the centre, a film by El Mehdi Azzam documents the research and workshops behind the installation.

Saudi Arabia’s pavilion is also designed around the construction of a specific architectural element. Over the duration of Biennale, visitors are invited to hang clay tiles onto a framework structure, slowly filling the space. The text on the wall attempts to give this performative act a sense of gravitas, but it all seems somewhat shallow and phoned-in, with its explanation of “a collaborative effort, pluralistic yet finding common ground in its shared desire to improve the human condition.” Kuwait, in a warehouse in the south of the city, explores a decolonised future, considering ways to rethink the nation’s post-Second World War modernist planning which resulted in the destruction of historic buildings and places.

Türkiye highlights its own disused buildings, searching for stories in abandoned or uncompleted projects, narratives that might support new growth and identity to fight developer-led ideas of beauty and objecthood. They suggest that a nation need not build grand new narratives or buildings so much as seek to reveal those present within that which exists – physically, culturally and politically. Across the Biennale, and as exemplified by the pavilions mentioned already, very few nations use the platform to push a singular new building or development project so much as explore conceptual or aesthetic lines of inquiry. It’s a focus that risks annoying certain members of the architectural community, especially those who desire models, scale drawings and design proposals. Patrik Schumacher, principal of Zaha Hadid Architects, publicly proclaimed Venice an “anti-architectural biennale … that does not show any architecture.”

Yet amongst the conceptual presentations one can find grand architectural projects, many connected to the building boom in the Middle East. NEOM, and its ambitious idea of The Line, a 170km-long sci-fi-infused idea for a new Saudi Arabian city, are presented in Venice in the form of a collateral event featuring physical models, while Qatar presents a smorgasbord of iconic gestures: an OMA-designed Auto Museum, heavily referencing Mies van der Rohe; a Prep School by Philippe Starck; the vast Art Mill Museum complex from ELEMENTAL architects; Herzog & de Meuron’s Lusail Museum on Al Maha Island; and a toy-blocks-inspired Dadu Children’s Museum from UN Studio. None of these, it should be noted, are architects from the region.

Imagery is not yet public, but two museums for AlUla were also announced. This year’s Serpentine Pavilion designer Linah Gotmeh will design a contemporary art museum, while Asif Khan will compose the Museum of the Incense Road. Both are nuanced architects, more interested in material and delicate atmosphere than the generation of starchitects before them – including all those in the Qatar list above. Their appointment may signal a shift away from shapes-in-landscape architecture by firms with no connection to the locality towards ideas from a new generation with connections to the region and demonstrating a more considered relationship to landscape and culture.

The Venice Architecture Biennale runs until 26 November 2023