The recent opening in Kazakhstan of the Almaty Museum of Arts, Central Asia’s first private museum of modern and contemporary art, signals a raising of the bar for the region and beyond.

The tectonic plates of art in Central Asia are shifting. Hot on the heels of the region’s first biennial in Uzbekistan (see page 126) comes a new museum in Kazakhstan that looks set to establish new standards in terms of design and programming. Opened with much fanfare in September, the Almaty Museum of Arts is dedicated to modern and contemporary art and is the brainchild of entrepreneur, philanthropist and collector, Nurlan Smagulov. “Art has had a profound impact on my life,” says Smagulov, “and it is my hope that the museum offers the same sense of inspiration and connection to others.” Smagulov’s personal collection of more than 700 works of art from Kazakhstan and wider Central Asia, as well as pieces by leading international artists, has been built over the past three decades and will form the bedrock of the museum collection.

Designed by architects Chapman Taylor, the striking new building extends over more than 10,000 square metres and draws its inspiration from the elemental mountainous terrain that surrounds Almaty. The facades of crisp angled limestone house a variety of galleries and other spaces arranged over two levels and accessed from a dramatic light-filled atrium called the Art Street. The views from within expand across the city skyline, studded by rapidly proliferating high-rises and designer malls, towards the traditional landscapes of the Tien Shan mountains beyond, as if to emphasise Kazakhstan’s fast-track synthesis of old and new.

The museum is located on one of Almaty’s main arteries, Al-Farabi Avenue, the very name of which underlines the rich cultural continuum of Kazakhstan. Abu Nasr Al-Farabi was a philosopher and music theorist, whose Grand Book of Music was one of the most influential tomes of its day. Born in c.870 CE in what is now Kazakhstan, he died in Damascus some 80 years later, after spending many years in Baghdad – highlighting the centuries-old intellectual and cultural connections between Central Asia and the most important centres of the Islamic world. It is these historical linkages that Smagulov and the museum’s curatorial team are aspiring to build on and develop further through a programme of exhibitions, performances, talks, workshops and other activities. “Our vision is to spark curiosity, dialogue and global engagement with the cultural wealth of Central Asia,” explains artistic director Meruyert Kaliyeva. “By grounding the museum in local histories while embracing global perspectives, we hope to build a space where art can be both a reflection and a catalyst for change.”

Two landmark exhibitions celebrate the opening of the museum. The first, Qonaqtar, features work from the museum collection that is focused on the regional traditions of hospitality (qonaqtar is Kazakh for ‘guests’) and migration, as well as the ancestral role of aqyns or poet-storytellers. It draws together paintings, graphic works and sculpture spanning from the 1940s to the present day, offering an absorbing snapshot of the foundations of modern art in the region as well as Kazakhstan’s own trajectory from the contraints and tensions of the Soviet era towards the country’s confident and independent status today. As artists sought to forge a distinct and modern Kazakh identity, they were forced to navigate a range of cultural and political obstacles. Inga Lāce, the museum’s chief curator, remarked on how, when exploring the collection, she “was struck by recurring images of gatherings, food and the landscape of the steppe, and wondered what lay behind these seemingly idyllic scenes.”

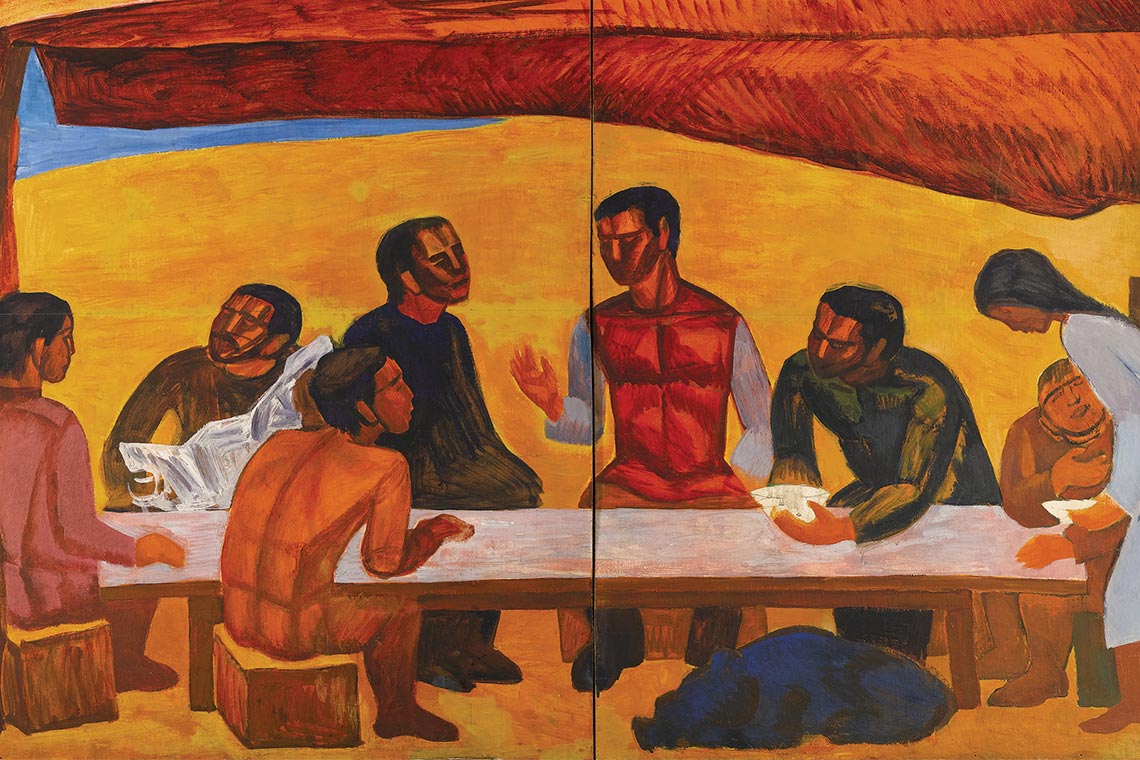

Enhanced by excellent interpretation via wall-mounted panels in three languages, the show unpicks a range of hidden stories, skilfully weaving together key themes in the last century of Central Asian cultural history, from folklore and landscape to transnational solidarity and modernist aesthetics. Seminal pieces include Aisha Galimbayeva’s Shepherd’s Feast (1965), celebrating themes of hospitality and celebration as seen through women’s eyes, and Salikhitdin Aitbayev’s On the Virgin Lands. Lunchtime (1960s), depicting a moment of rest (and a meagre lunch) during the Soviet ‘Virgin Lands’ campaign which brought volunteers to cultivate the Kazakh steppes and displaced thousands of people. Other standouts are Sakhi Romanov’s On a Visit (1967), humorous and dynamic in equal measure, and Warrior by Maktum Qisamedin (1973), a stunning linocut that speaks to enduring themes of strength and resilience that emerge across the whole show. Qonaqtar marks a notable public debut for many of the works on display.

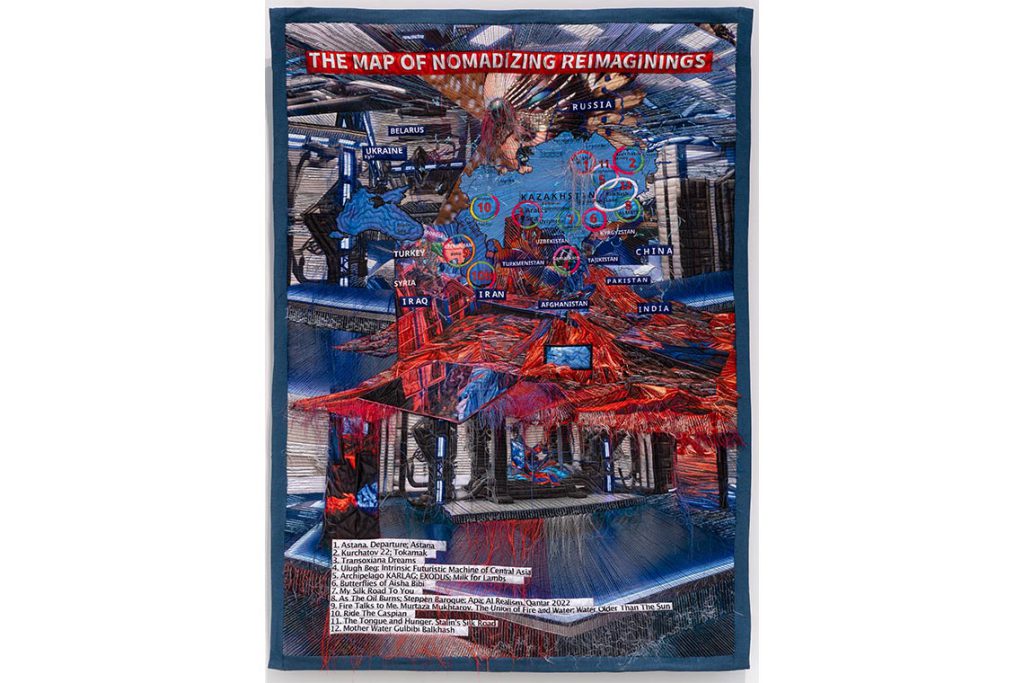

Presented in the other major temporary exhibition space isI Understand Everything, the first retrospective of the seminal artist, Almagul Menlibayeva. Born in Almaty, she has enjoyed a career extending across almost four decades and spanning myriad media, from textile, painting and printmaking to performance, photography, video and, most recently, experimentation with AI. Curated by Gridthiya Gaweewong of the Jim Thompson Art Center in Bangkok – a choice that articulates the museum’s affirmedly global perspective – the show is full of treasures, not least The Map of Nomadizing Reimaginings #3, (2025), one of Menlibayeva’s superb ‘cyber-textiles’ in which she treats new technologies as an extension of traditional felt making.

The exhibition elegantly articulates the artist’s personal cosmology, built around issues of identity, belonging and endurance, and unfolds across two chapters. The first (on show until January 2026) focuses on symbolic geographies of Central Asia – the steppe, the tragedy of the Aral Sea, the ancient landscape of Transoxiana and the Semipalatinsk nuclear test zone – while the second (opens February 2026) will look at sites of memory across Kazakhstan, including Stalin-era labour camps, and how fertility, mythology and nomadic tradition have impacted the agency of women and resonated along the historical trade routes that thread the region.

Equally noteworthy are the museum’s four artist rooms, one extending to double-height, offering immersive experiences with works from the museum collection that are intended for long-term display. Installations by Richard Serra, Anselm Kiefer, Yayoi Kusama and Bill Viola make their first appearance in the region, with such heavyweights supported outside the building through pieces by Alicja Kwade, Jaume Plensa and Yinka Shonibare, whose Wind Sculpture (TG) II (2022) greets visitors as they arrive. It is a statement roll-call, reflecting both the quality of Smugalov’s collection and the ambition of this impressive new museum’s wider vision as it moves forward.