Four decades after the Tehran exhibition that led to his exile in the USA, Nicky Nodjoumi still uses his creativity to speak up against authoritarian regimes.

Three hours of the exam had passed when the professor walked by and said “That’s no good!” Nicky Nodjoumi was seeking entry into Tehran’s University’s Bachelor of Fine Arts and had been tasked with turning the Italianate sculpture in front of him into an A3 drawing. “I was meant to fit the image from the top to the bottom of the page, but I had a small drawing in the middle – the paper had an official stamp, I couldn’t change it,” he says, recalling the anxiety. With his acceptance hanging in the balance, an exam administrator came across to him. “Turn the paper over,” he suggested, “you have one hour left.” It was a timely reminder to the young artist that a second side and fresh new start was possible, albeit with a sense of urgency.

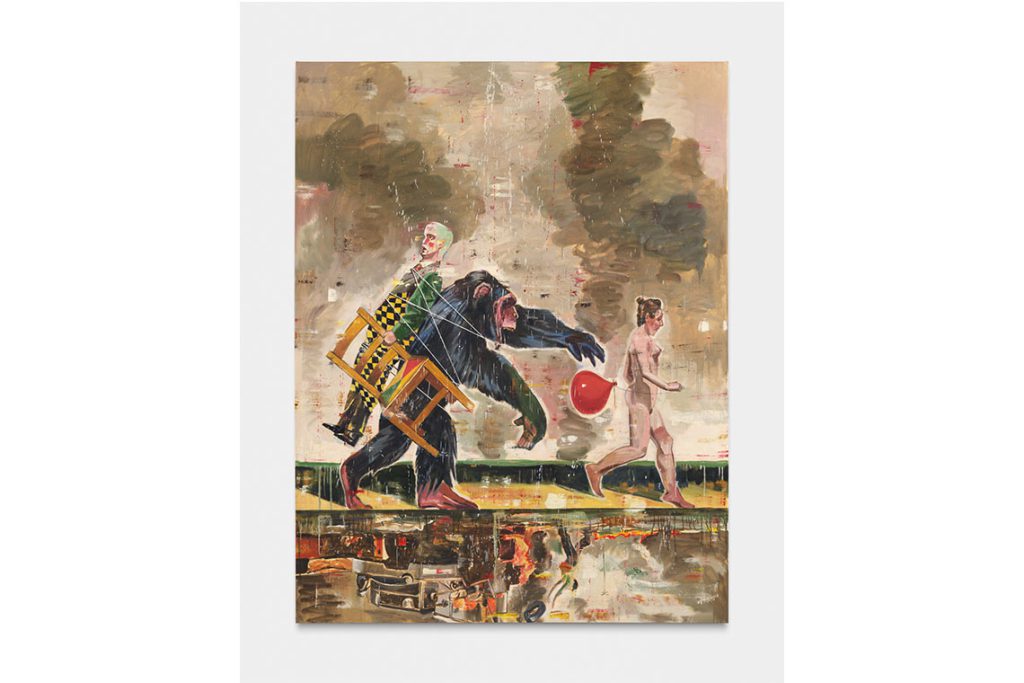

Born in Kermanshah, Iran, in 1942, Nodjoumi admits he was a terrible student in everything other than art. The first painting he recalls making was of a rooster, and he also remembers the feeling of a possible talent within after his teacher held it up as an example to the class. Animals have frequented his art through the decades since. A dog sitting on a chair. A donkey navigating a tightrope. A fish tied with string. Suited men with rabbit heads or chimps perched on their shoulders. Butterflies, alligators, birds, cows and more populate his busy and excitingly confusing canvases.

These works, however, are not pastoral scenes or representations of nature as much as expressions of human nature. Energetic, oblique, with imbued anxiety and violence, Nodjoumi’s practice – and life – is dedicated to those fighting for freedom against oppressive political regimes. It is a fight deeply rooted in his Iranian history, both before and since the revolution.

Following the development of a heart problem, in 1969 Iranian doctors advised Nodjoumi to travel to the United States for surgery which they could not undertake. Once in New York, he was introduced to the city’s Iranian diaspora and particularly to the Iranian Student Association. The urgency and directness of their opposition to the Shah seemed at odds with the slow poetics of Nodjoumi’s painting practice, and so he began making protest posters in support of Iranian freedom fighters, drawn to the graphic immediacy and power of such imagery to spread a message. He later enrolled at New York University to study filmmaking, a medium he believed might offer the strongest avenue for creative political protest – with the added bonus of a visa extension – and later transferred to an MFA at City College. Endeavouring to integrate his political passions within his work, he found the system unresponsive, saying that “after classes, I asked teachers what the relation between art and politics is, but they would just look at me strangely.”

While politics might not have been in his classroom, Nodjoumi found it everywhere else. Joining in with protests over tuition fees, the Vietnam war and civil rights, Nodjoumi’s heart was still in an Iran from which he felt increasingly remote. Monitored by the Shah’s secret police and with the 1979 revolution brewing, he was prevented from taking up a teaching position at Tehran University but still offered an annual exhibition and so returned home, leaving his wife – fellow Iranian artist Nahid Hagigat – and daughter Sara in the USA.

After the Shah fled into exile, Nodjoumi’s activism was now in opposition to the emergent and violent regime led by Ruhollah Khomeini and the so-called “hanging judge”, Chief Justice Sadegh Khalkhali. At one protest Nodjoumi was arrested at the point of a bayonet, then convicted and sentenced to 100 lashes. “We were hoping that that we would establish democracy in Iran, but it resulted in one of the harshest, most brutal regimes of all time,” he says of the Islamic republic which has since controlled Iran in place of the freedom he had fought for.

Unexpectedly, in 1981 he was still invited by Tehran’s Museum of Contemporary Art for his annual exhibition. His paintings had evoked symbolic imagery of struggle, crowds and figures running, but this exhibition, Report of a Revolution, was more direct, including critical depictions of Ruhollah Khomeini amongst images of blood, violence and execution. The following morning’s newspapers featured his work on the front page with headlines including “Nodjoumi is a traitor” and “his work is evil”. Fearful of capture and execution, he immediately returned to the USA.

This period of Nodjoumi’s life is the central component of a forthcoming HBO documentary film, A Revolution on Canvas, directed by his daughter, Sara. It follows their quest to reclaim the paintings from that 1980 exhibition, many of which are still in the museum’s basement storage alongside a collection worth billions of dollars, including works by Bacon, Duchamp, Van Gogh and Monet.

Both the film and Nodjoumi’s work, however, go beyond those tumultuous years of the Iranian revolution and its subsequent fallout. 2023 is, after all, not short of global protest, power and politics – not that he considers his work ‘political’ art: “That phrase has a heavy weight. I don’t mind it, but for me it’s the idea of general fighting, fighting for justice, not just politics. This is more interesting for me – but then to me, everything’s political anyway.”

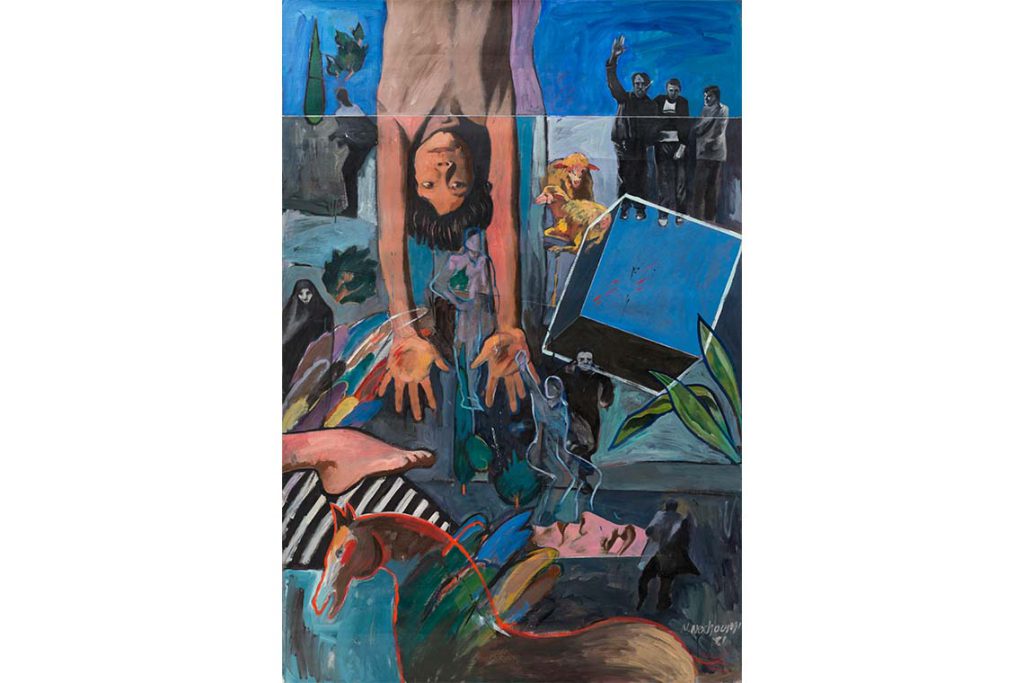

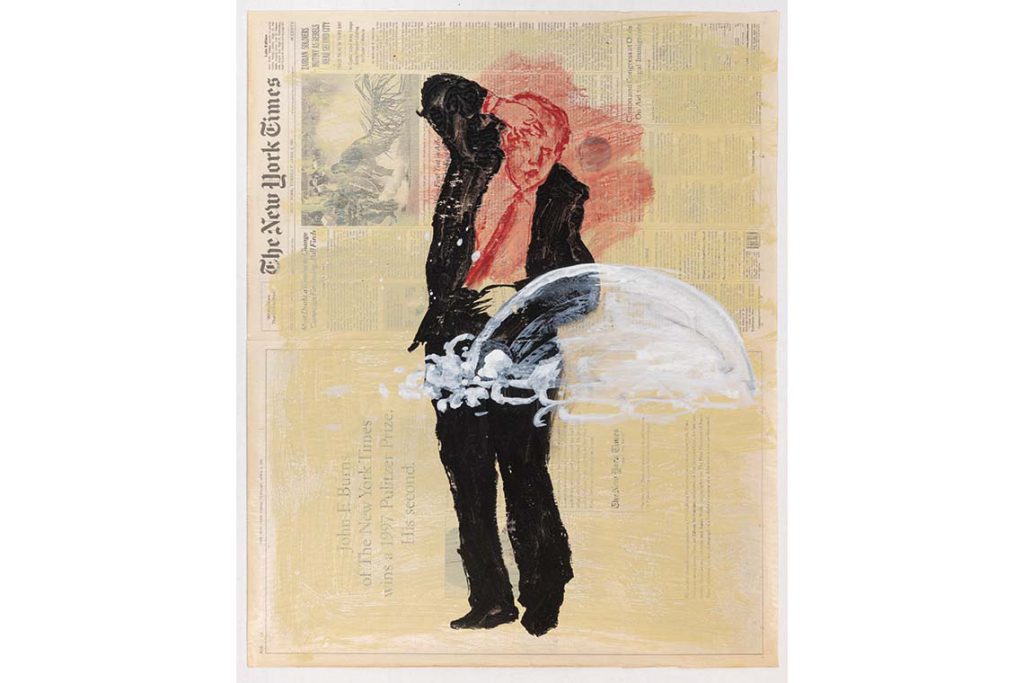

To improve his English and digest the world’s affairs, Nodjoumi used to read the New York Times daily, but realised that the images attracted him more than the words. “Different heads, gestures, all these things speak to me,” he said of the images he began to cut out and keep, adding that “if there is movement, I will take it.” He then dismembers the photographed bodies to use in collages for planning future paintings. “I’ll work on the collages and preliminary studies more than the paintings,” he adds. “In a couple of days the painting is done, but the image takes time to create.”

Thus, the characters in his paintings are not single figures – as his 1981 representation of Khomeini was – but political chimaeras formed of numerous figures of power. Through this abstraction he speaks less to a singular political force but more of the means, mode and positioning of inequality, force and systemic power. Recently, he made protest posters for rallies in support of women’s rights in Iran, but he is also aware of issues all over, including the Global North. “I think the United States is getting worse, the right wing is coming up,” he says, adding that “it started during Trump, it’s right in front of us now.” He retains hope in the fact that in the USA and Europe there are structures so people can change a trajectory and that change is visible, that “you can see people struggling for change” – a liberty unafforded to many global citizens.

With Iran he has less optimism, foreseeing a “dark future” for his home, even if deep inside he still has some of the utopian faith developed when protesting for democracy against the Shah. “I have a hope that something will happen and that, without bloodshed, freedom will come to Iran so they can have lives as others do,” he offers, retaining that simple dream of turning the page over and starting again afresh.

This profile first appeared in Canvas 109: Smoke and Mirrors