The second edition of the Henie Onstad Triennial for Photography and New Media serves up a reminder of the roots of modern humanity in nature.

If you use Netflix as a barometer for measuring social anxieties, it would appear that things are bleak. The dystopian narrative is as ubiquitous today as the romcom was in the 1990s. Filmmakers would have us believe that environmental collapse, political corruption and rabid consumerism are about to call time on humanity. Walking through Oslo’s Henie Onstad Kunstsenter, one can only sigh in recognition.

The second edition of New Visions – The Henie Onstad Triennial for Photography and New Media is focused on “resource extraction, energy distribution and data harvesting”, an intriguing and concerning survey with a particular emphasis on artists from the Middle East and North Africa. The museum is a rare example of Norwegian mid-century concrete-and-curves architecture: low-lying in the pines, it faces the Oslo fjord like a Brutalist look- out post, an apt location for an event that surveys the tides of technology as well as the ebb and flow of societal norms and artistic expression.

Susanne Østby Sæther, curator at Henie Onstad, explains that while surveying contemporary art from the past three years, she was struck by how the treatment of resources and infrastructures, as well as the repurposing of traditional ornaments, was a common concern. “These were also highly relevant and timely themes given the intensified geopolitical situation throughout the last year,” she says. The war in Ukraine, elevated energy prices, erratic migration patterns and corruption all feed into the works at Henie Onstad’s critically sharp and timely exhibition.

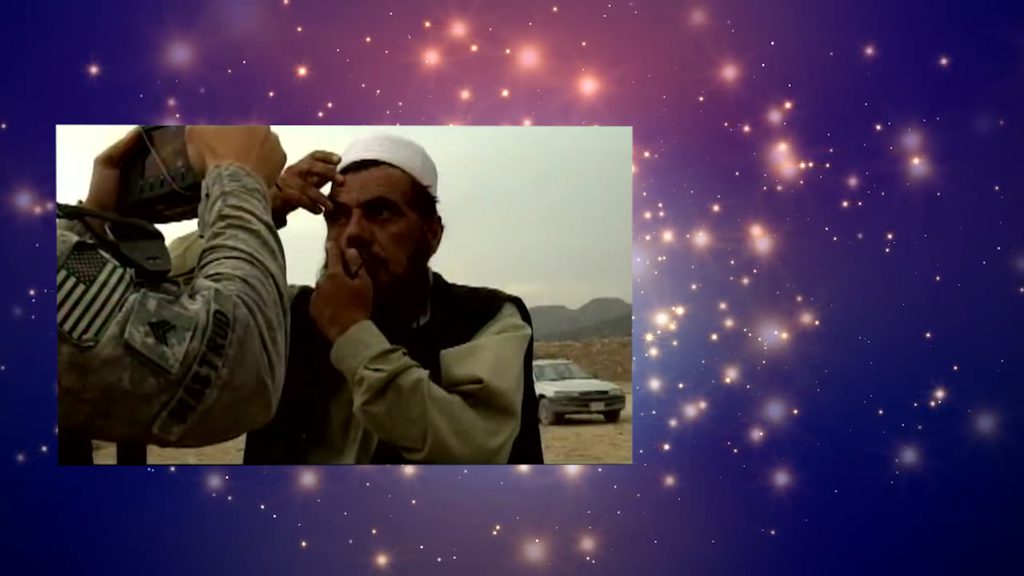

The rarely considered resource of light is explored by the Lebanese artist and writer Haig Aivazian. His spellbinding video installation All of Your Stars Are but Dust on My Shoes (2021) investigates how light is used as a tool for state and military control, through the imposition of blackouts and curfews and the planning of public lighting systems. Blending his own footage with archive film of New York, Paris and, in particular, his home city of Beirut, the result is a mesmerising and crackling tapestry of visual rhythms and beats. This palpitating work highlights how a basic right – to see and be seen – can be manipulated. “They were initially called police lights,” explains Aivazian. “Of course, no one calls them that today. They call them city lights.”

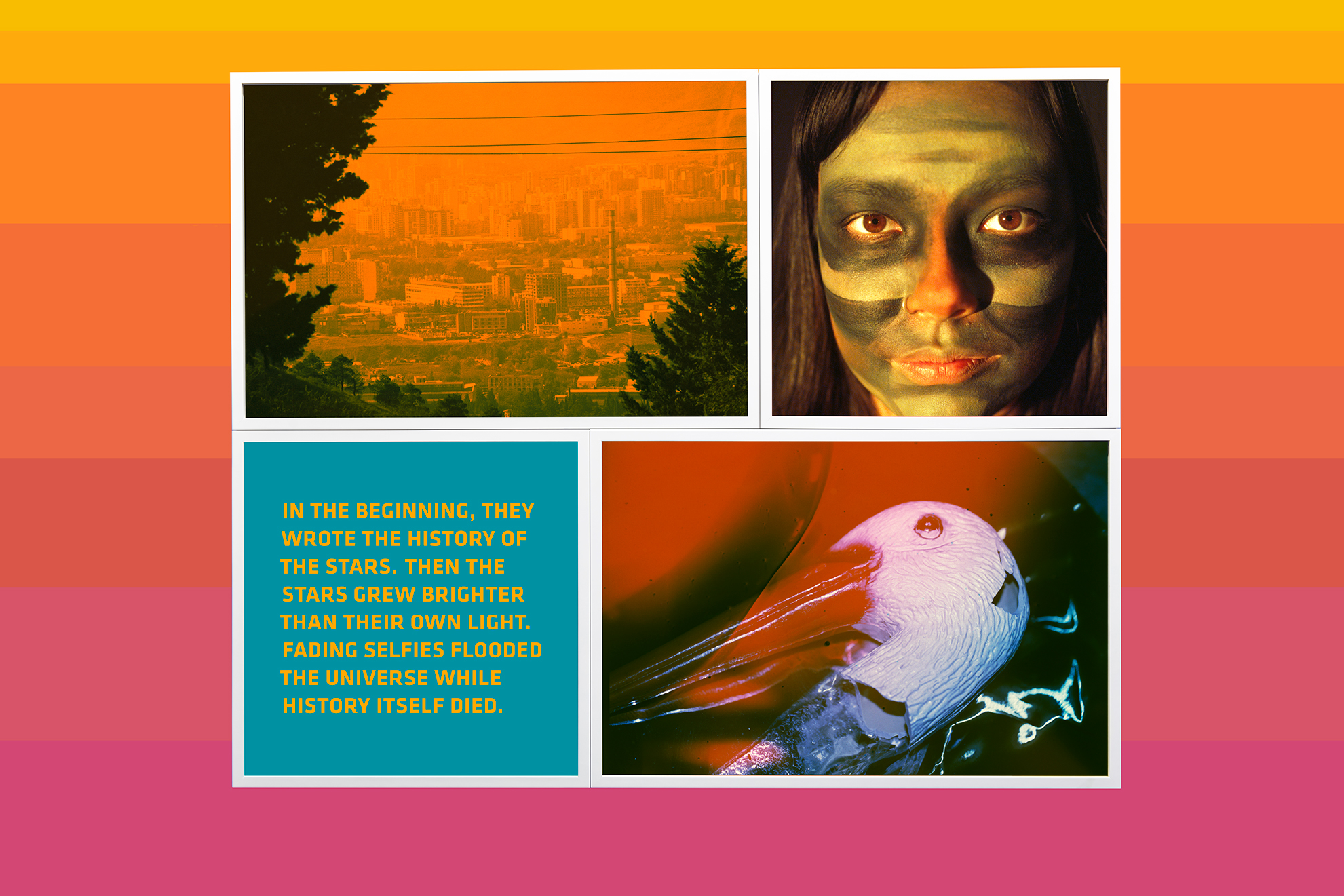

Of the more traditional photographic series on view, two explore social layers in high colour. In a commission for the triennial, UAE artist Farah Al Qasimi has produced a retina-popping explosion of images of the Emirates. They detail a post-oil culture in which floral motifs hint at the sapping of nature’s bounty. Al Qasimi incorporates the contemporary – LED images of roses, synthetic flowers, printed petals on plastic carrier bags – with the timeless, such as the silhouette of a branch on a wall. Her trademark use of Technicolor palette reigns throughout.

Equally vibrant is the work of Marat Dilman, a Kazakh photographer with a keen eye for the intersection between technology and tradition. His compositions capture a post-Soviet landscape that bridges futurism and folklore: an embroidered Kazakh hat sits on a robot’s head, an amulet hangs from a CCTV camera, public spaces are decorated with garish artificial depictions of nature. Dilman’s unnerving images float in the air somewhere between documentary photography and surrealism.

The range of malignant interventions and seizures addressed at Henie Onstad is broad: pollution in the Baltic Sea, underwater data servers, the part petrochemicals play in the clothes we wear. One wonders if the issue of resource extraction is a sensitive subject in Norway? After all, its national wealth is founded on oil. “It is heavily debated and deeply politicized,” acknowledges Sæther. There are specific issues, she says, around “new production licenses for oil and gas extraction, scenarios for energy futures beside fossil fuel, prospects for deep sea mining, the implication of ‘green’ wind power for indigenous lives and livelihood.” Even in the far north, the topic is hot.

One of the highlights of New Visions is Seif Kousmate’s photo-series on the endangered oases of Morocco, works that blend reportage and landscape photography – shots of workers in the irrigation channels, the crumbling facades of buildings – with conceptual elements (several prints are collaged with the dead skin of palm trees). “My interest in the oases is purely one of an individual who understands the importance of preserving ecosystems,” Kousmate explains, adding that they have become dramatically altered by climate change, resulting in “reduced agricultural yields, poverty and the deterioration of natural resources. Morocco has lost two-thirds of its 14 million palms over the last century.”

The aim of New Visions is to showcase experimental work that pushes the technical and thematic boundaries of photography. This edition is particularly successful in this regard: the 22 artists included have introduced elements of AI, animation, sculpture, film, textiles and collage into their practice. Likewise, the exhibition toys with notions of reality.

Photography is no longer a medium in which prints are simply framed and hung on the wall. Today, the medium is “entangled with algorithmic culture”, notes Saether.

Most of the work, understandably considering the theme, leans into gloomy territory. Neïl Beloufa, the French-Algerian conceptualist, provides rare and welcome relief with his “hosts” – anthropomorphic sculptures created out of video screens – which talk to visitors (they also provide selfies for your social media accounts). In cheery yellow and cosy orange, they seem friendly enough; but they also reference how IRL turns into URL. Beloufa’s work implies that we are all becoming gamified, little more than data for digital sponges. His eerie Frankenstein-meets-Pokémon hosts are fun (and a little creepy).

Sæther suggests that this thrillingly pessimistic show has its happier aspects. “While the themes are acute, dark and speak to the precarity of the moment, many of the works themselves are colourful, playful and generous in their sensuous and visual qualities,” she says. “I see these qualities in themselves as positive threads that also invite hope.” Even so, on balance, the view from Oslo – while creative and considered in its substance – is distinctly ominous in tone.

New Visions runs until 17 September 2023

This review first appeared in Canvas 108: The Root of It All