L’Ecole Van Cleef & Arpels, the school of jewellery arts established by the brand, recently wrapped up its second edition here in Dubai. In this year’s programme, art history was a key component of its courses, and its accompanying exhibitions broadened the world of jewellery-making from craft to context. Canvas explores two of these exhibitions to find out more.

Across cultures and through history. Jewellery has been used as a form of adornment and a means of distinction. The craft of creating Jewellery, from its beginnings as metalwork to current practices of gemology and precious stones, has always adapted to the prevailing aesthetics of its time, while also responding to a wider Historical moment. This year, Van Cleef & Arpels L’Ecole for School of Jewellery Arts), returned to Dubai and presented a series of exhibitions that expanded perspectives on jewelry craftsmanship and design. The special three-week program (28 March-13 April) included a series of 14 courses, six talks and creative workshops, as well as four exhibitions displayed in Dubai Design District.

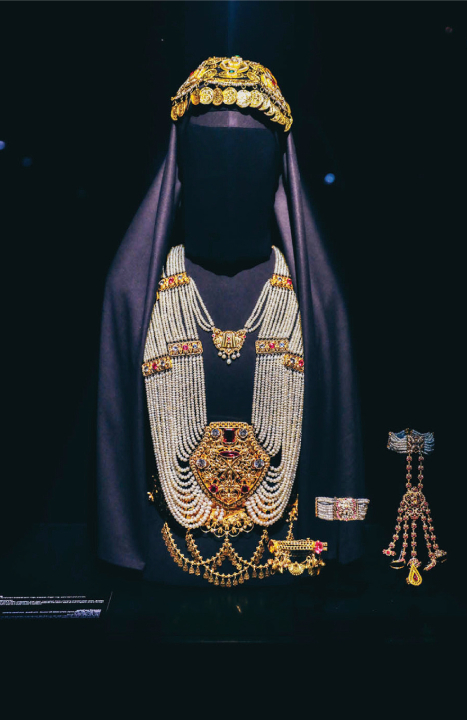

A particularly eye-opening exhibition – entitled Hidden Treasures: Jewellery from the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia – drew from the Saudi Arabia’s Art of Heritage collection and shed much-needed light onto its material culture. Started over 30 years ago, the Van Cleef & Arpels Art of Heritage Collection has always aimed to preserve cultural heritage from the Arabian Peninsula through garments, textiles, jewelry and artifacts, and one can see how women played a major role as patrons and producers of these tangible histories. For example, the show presented a series of bejeweled coverings and face veils worn by Bedouin women in the 20th century. Instead of the plain black niqab or face covering seen today, these were heavily embellished using coins (and thus conveniently used as a carrier of Currency), and beads, fashioned according to regional styles.

The collection also featured headpieces, necklaces, earrings, rings, waist belts and other accessories, the choice of metals and designs revealing aspects of Saudi Arabia’s trading history. Take the pattern of a silver choker from the Kingdom’s Eastern Province, which bore influences from the Persian/Afghan border regions with its thick, robust designs using a chainmail pattern. In the north of the Kingdom, copper, brass and silver were often paired with coral, glass, and pearls, while the central region maintained an affinity for medallions and head ornaments.

Another exhibition that explored the impact of history and societal change on jewelry-making was Pearl Merchants: A Rediscovered Saga between the Gulf & France at the Dawn of the 20th Century. Its lengthy title sets out its premise, a research-driven display that traced the links of pearl trading in the 1920s (to 1939) between France and countries such as Kuwait, Bahrain and what were then the Trucial States (before becoming the United Arab Emirates in the 1970s). The museum-style show highlighted the many factors that fuelled the pearl trade and revealed how shifting fashion trends also boosted demand and choices of material. As small natural pearls became à la mode for evening bags and necklaces, so their market value rose. By the late 1930s, however, oil was slowly being discovered in parts of the Gulf, reshaping economies and marking a shift towards modernization. By the time the Second World War was on the horizon, the pearl trade between France and the region had come to a halt.

Creating these connections between Jewellery and the forces that shaped the industry enlightened visitors with not only a contextual framework but also a deeper appreciation of how jewelry, which at times may be perceived as a luxury remote from the conditions of society, has the potential to impart the history and stories of its wearers and makers.