Occupation is as much a state of mind as a bodily reality for the Jerusalem-based Palestinian artist, who explains how she uses art to give hope to an uncertain future.

Canvas: You have described the theme of occupation in your work as both physical and mental. How do you distinguish between the two?

Raeda Saadeh: Usually, when people see the word ‘occupation’, they immediately think of the Israeli-Palestinian occupation. But women also live under occupation, by society, culture and many other forces. I talk about this from a female perspective because I am a woman and, although I leave room for interpretation in my work, this conflict with society is generally present.

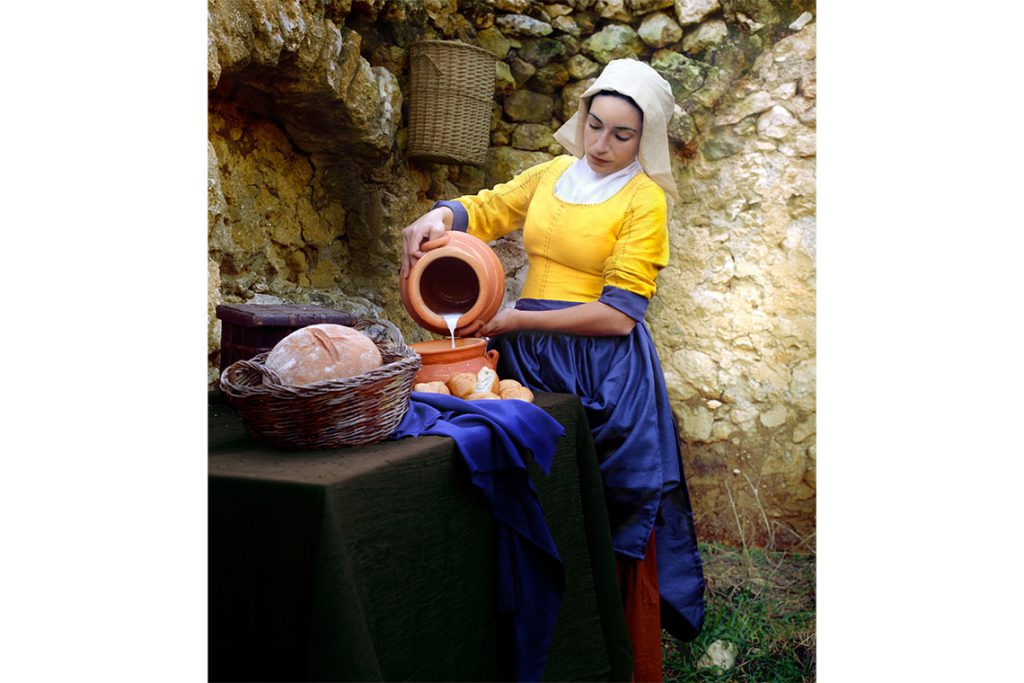

You often stage yourself as characters in your work, for example in your Great Masters series. Is there a sense of reclaiming these representations of the female body?

Yes, but there is also a conversation between me and the West. Each work in the series has a different story from Palestine in 1948. In Diana, I’m in a village near Jerusalem, which belongs to Palestinians but where they cannot use the land because of restrictions. In the Milkmaid, I’m in Al-Burj, a village between Jerusalem and Jaffa, which in 1948 was a place where farmer would stop for a break and a rest. [The Israelis] destroyed the ceilings of the houses, so no one could live there. We don’t know the real stories of the women in those famous paintings, just like many people do not know these stories from 1948. So, I give them back an identity.

For your series on fairy tales, how do you go about deciding which characters to stage?

I try to use stories with universally known characters. The space is also very important. In Little Red Riding Hood, I’m standing in the financial district in Tel Aviv. As a Palestinian, I am not allowed to go there, so I took the photo on a Saturday, when no one is about. The character in the original story was in the forest. For me, this is the forest. She was going to give food to her grandma, I am carrying Jerusalem cookies in a basket, trying to take them across.

What led you to stage your own body in your work?

When I was an art student in 1998, a teacher asked us to make a sculpture inside a sculpture. While thinking about it, I felt that I was a sculpture and so I decided to do something with my body. I had a white wedding dress on with a black veil. The others could just hear my voice and my breathing. I thought the teacher would not like it, because she had asked for an object. When I was done, she said, “That was a nice performance”. I asked her, what performance? She said that’s what you did, it’s called performance. That was the moment when I met myself, found my identity in art. I felt very happy. Sometimes it’s photography, video or live performance, but I’m always there.

Are there times when you feel more drawn to photography, rather than to performance art or video?

I usually decide from the beginning what it will be. I made a video work once in the North Pole, where it was way below freezing. There was no audience, but I was still doing a performance. This act of performing is a constant thread in my practice, whether or not the final work is shown as a video or photograph, or performed for an audience. In my latest exhibition in Amman, Dear Viewers, there is one work, Sea (2024), in which I am hung from a fishing hook over the water. It’s still performance, a scary one, as I am not a good swimmer, but you can see it only through photography.

You’re describing a very physical process, putting yourself in difficult circumstances.

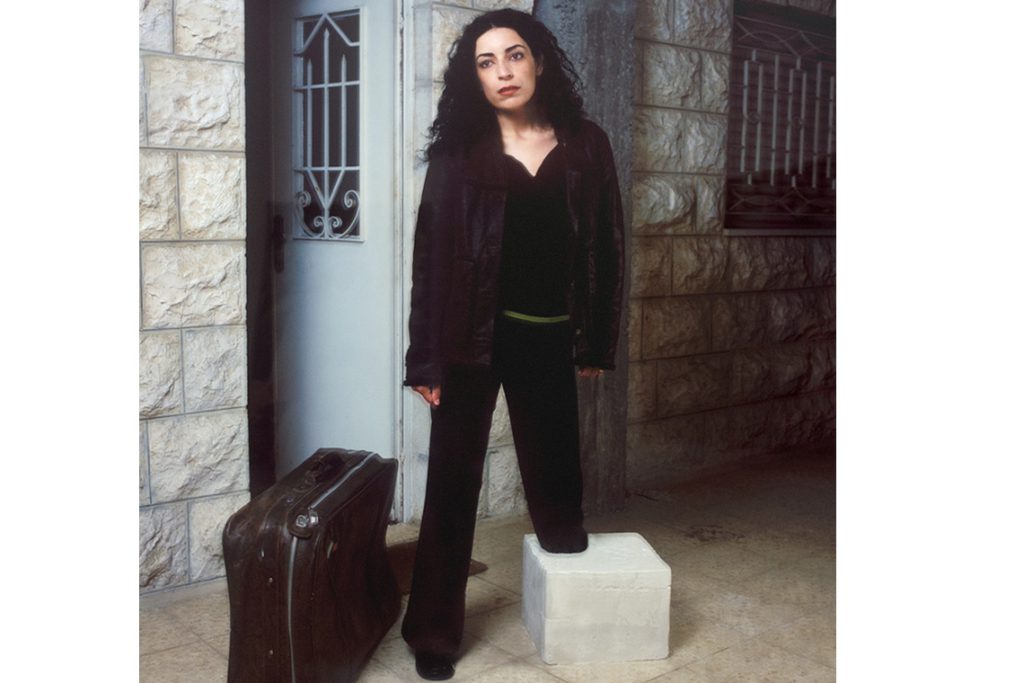

I want to execute my ideas exactly as I imagine them. If my work is fake or edited, it doesn’t feel authentic to me. In Crossroads, I made a cardboard box with cement inside it and a mould to fit my leg. I wanted the heaviness to look and feel real, but hadn’t thought about the drying process. The cement started squeezing my leg, painfully. But I was happy because it felt real.

You’re Palestinian. You’re living in Palestine, where the body is almost a political tool. How do you navigate this in your work, when you’re staging yourself?

Living under this situation, with Israeli citizenship, it’s difficult for me to say where I am, where my body is. It’s very similar to the separation wall, because I’m here but I’m in between. The wall for me is a huge, very scary thing. In most of my work, I use humour, to say, “Okay, all of you, all the world, all the people in the world, you look and you don’t do anything”. And me with my body and me as a woman, I’m doing the job that others cannot do. I’m moving the wall, taking it, wanting to throw it… I’m standing on the Jerusalem side, not the West Bank. When I was taking the photos, some soldiers came and tried to stop me. I knew the Israeli law, it was a public area where you can take pictures. They said, you’re not allowed to walk here. I asked them why not, and they said because it’s dangerous, because sometimes people throw rocks from the other side. I said, ok, it’s my business, it’s not your business, and I continued with my work. Before the war, I could have this discussion. Now, it’s changed. They might not give me the time to answer.

You’re staging yourself, staging women, and there’s a sense of hope for the future as well. Has that changed for you since the war on Gaza started?

It’s certainly more difficult, but I still have hope for the future, because we must. I have a daughter, I have nieces, we must give them the hope. We must do it. If we just give up, we kill something inside them. As an artist, I’m doing exhibitions also to show others it is possible to succeed, to talk through something, not only art, through writing, through anything. Whatever you’ve got, you can talk through it.