Ever inspired by the natural cycles of life, the artist explores a spiritual pathway through senses of home and belonging.

Hailing from the Golan Heights, the Israeli-occupied mountainous territory in southwestern Syria, Randa Maddah grew up among a Druze community that believes firmly in the notions of reincarnation and rebirth. As we settle down for our conversation and start exploring her practice, she makes clear how, as bittersweet and undesirable as death can be, the end is only another beginning in her eyes. I understand immediately how such a philosophy underpins her delicate canvases of fairylike creatures floating in serene yet melancholic scenes of greenery, exhibited this autumn in her exhibition Hanging Gardens (ended 10 October) at Tabari Artspace in Dubai.

Featuring paintings, sketches and notebooks, Hanging Gardens was Maddah’s first solo show in years. It looked primarily into the imperfect ties most of us have with land and at the pain that comes with being far away from ‘home’. One especially striking image was Hanging Gardens #1, in which a female character, laying down peacefully with her eyes open, is greeted by a floating figure, resembling an angel of death, one might infer. It is a scene of dignity and grace, where the recumbent individual’s long hair is handled with care by a brown creature, and another female onlooker is standing in the distance, perhaps chanting as she absorbs the solemness of the cycle of life.

While speaking with Maddah on Zoom while she is visiting family in her home village of Majdal Shams, I notice how much of an intellectual and literary mind she possesses and yet still articulates herself in a natural, non-pompous way. Her symbolist art, while reflecting her own personal experiences, is equallyn informed by history and mythology. Within an hour, she has talked about Mesopotamian and Sumerian legacies, baroque art, the sixteenth-century artist Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Jorge Luis Borges’s 1950s publication, The Book of Imaginary Beings, and Edward Said’s memoir, Out of Place. I mention that there is a storybook element to her work, to which she replies that historically authors humanised nature in order “to understand it and its violence”.

The title of Maddah’s latest show was inspired by the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, one of the seven wonders of the ancient world and a legendary tale of grand romantic gesture and longing for homeland. The iconic story relates how the Babylonian ruler, King Nebuchadnezzar II (r. 604–562 BCE), built a paradise of gardens for his homesick wife, Queen Amytis, to remind her of her birthplace of Ecbatana, an ancient city in modern-day Iran.

Although there is no evidence that the gardens actually existed, Maddah was much taken by the story, for she saw in it her own. “We don’t know if we are talking about something real or imaginary,” she admits to me. “I read about it by chance, and felt that it represented my mental state.” Perhaps the resonance came from the fact that not only has Maddah grown up in a land occupied by another, but she also lives abroad, now working mainly in Paris.

The memories remain, however. For Maddah, the Golan Heights, an important water source and a natural marvel of mountains, valleys, fruit trees and waterfalls, were her own Babylon. “Everyone has a plot of land that they used to depend on for their own livelihood. We are essentially an agricultural society. It’s one of the reasons why people from the Golan Heights are so attached to their land,” she explains. “I always felt I was living at the end of the world. Can you imagine this feeling? It was strange and probably motivated my imagination, where I created worlds.” She remembers growing up with the four seasons and abundant nature, picking cherries and apples with family and friends and going for long walks. “It’s a part of my life and a visual scene that lives on in my memory,” she reflects.

Being raised under Israeli occupation came with its own set of challenges. Security concerns and the lack of freedom of movement aside, Israeli forces attempted to impose citizenship on local communities. It sparked a backlash with Golan residents, creating laws that protected their identity and boycotted the Israeli entity. In such tense political circumstances, art was a refuge for Maddah, even from an early age. “I never had the feeling that I wouldn’t be an artist. I always knew it,” she says. “It’s been a part of my daily routine. It’s a need.”

With the backing of her supportive parents, in the early 2000s she formally studied art – specialising in sculpture – at Damascus University. She has since experimented with film, drawing and installation art. Another defining experience took place when she studied etching in Jerusalem during 2007–08. She felt a sense of familiarity among the monument-filled streets of the Old City of Jerusalem, which reminded her of the old alleyways of Damascus. On a more personal level, there was also a sense of camaraderie, common cultural norms, as well as a pain shared with her fellow Arab Palestinians, who were also suffering from occupation. “Because of the political situation and border complications there, it was a painful place,” she recalls. “In Palestine, I felt more comfortable talking about our reality in the Golan Heights because our stories were similar.”

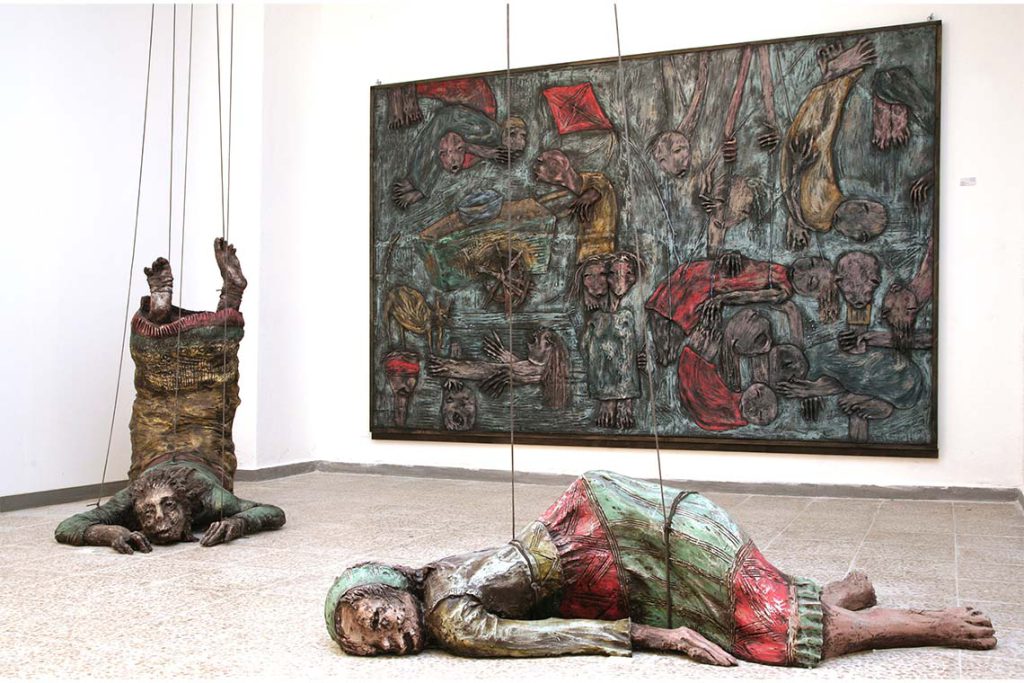

Maddah is a producer of images that are hard to forget: visceral, brutal and real. Figuration has been a consistent theme in her visually intense body of work, never more apparent than when the viewer is confronted with the haunting and decaying faces she created for her powerful ink series Faces of Damascus (2008) and Puppet Theater (2008). Composed of a harrowing installation of lifesize figures hanging torturously from ropes and acting as an expressive commentary on regional violence, these two collections of work were produced during Maddah’s stay in Palestine. “The work that I was making then was an attempt to reflect on political reality and its influence on society,” she points out.

Bullet on Paper (2015), black-and-white pencil drawings of child-like figures floating in a state of loss and lifelessness, was executed in the wake of the 2011 war in Syria. It is work that remains ever relevant during the current turbulent period of fighting between Israel, Lebanon, Palestine and Syria. “We are all in the same boat, sharing the same concerns,” says Maddah. After completing her Hanging Gardens series, she travelled to Majdal Shams for respite and inspiration, where some new ideas, pertaining particularly to the symbolism of the apple, are bubbling in her mind.

Like her hanging figures, Maddah is physically between places, but art is her permanent home – a safe space for her mind to wander freely. “I can imagine that any person, whether working in art or not, feels safe in one way or another when they are working with their tools and expressing themselves,” she says. “But maybe in art it’s more special because you are creating a picture of something imaginary, which becomes real through a sense of feeling.”