Let me tell you something brings new ways of looking at cats, letter-writing and the everyday to 421 in artist Mohamed Khalid’s first institutional solo show.

“In these words glimmer the Surrealist proposal for finding the marvellous in the banal,” writes art historian and critic Lori Waxman in Keep Walking Intently – The Ambulatory Art of the Surrealists, the Situationist International, and Fluxus (2017). It is often in the flânerie, or the stroll, where a casual observer becomes an analytical connoisseur of the urban fabric. So it is that the chance encounter while moving through the city is the well from which the work in artist Mohamed Khalid’s first solo exhibition springs. Hardly a new thesis, finding the marvellous in the mundane still never fails to engage an audience because it never ceases to be important in our increasingly urbanised lives. As a product of modern life, where it’s so easy to feel alone, casual observation rather than participation is simply a lifestyle for many of us. It can also be a tool of condescension. Walter Benjamin’s flâneur, for example, is an uninvolved but highly perceptive bourgeois dilettante.

Khalid, a self-described flâneur, does much more than observe in Let me tell you something at 421 (formerly Warehouse421). Here, flânerie is an analytical tool used to understand our world and maybe even find magic, or at least beauty, in it. The terrain he wanders through is made up of city streets, as well as the corridors of his memory and the landscape of his emotional life. Khalid’s encounters, experiences and memories play a key role in how he understands, takes part in, and portrays the world.

The exhibition’s seven newly commissioned works continue 421’s tireless support for young and emerging artists. Khalid is without formal training as an artist, apart from fellowships like The Salama bint Hamdan Emerging Artists Fellowship (another 421 programme), having left his undergraduate architecture studies after the first year. Yet in this first solo exhibition, a relatively new creative practice confidently takes shape.

Almost everything in the show is made by Khalid’s own hands, a dimension that is central to his practice as a way to counteract the hyperconsumerist culture he sees seeping into art practices in the UAE. In hand-drawings, handmade cyanotypes and hand-written letters, he works by pulling subjectivity and nuance from mundane objects and chance encounters.

When a security guard at his housing complex leaves a note on his car telling him there will be penalties if he parks his car illegally again, Khalid is charmed by both the beauty of the penmanship and the guard’s gesture of producing it. In handwriting that many native English speakers don’t themselves possess, a discernibly non-native English speaker has taken significant time to compose this letter. The intention was legibility, but the outcome happened to be beautiful. So beautiful, in fact, that Khalid was compelled to replicate the letter in Thank you, which opens the exhibition.

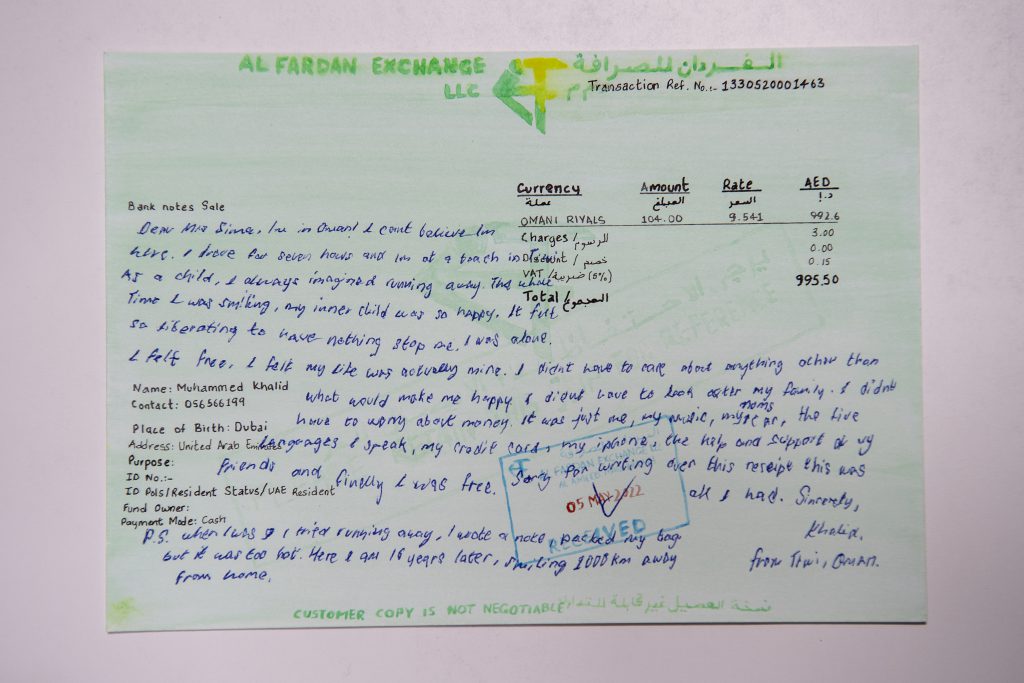

The guard’s graceful cursive proved too difficult to duplicate by hand and Khalid was forced to deviate from hand-drawing and resort to carbon tracing paper. In Khalid’s practice of replicating things by hand, he has drawn commonplace items like receipts and is known to change his replica of a parking ticket he received, for example, to give himself a nicer car. But perhaps to avoid corrupting the sanctity of the letter’s beauty, it had to be perfectly copied.

Part of Thank you is Khalid’s response letter to the guard, imagining a universe in which he could afford to continue parking illegally, telling the guard that he will continue to do so in order to receive more of his letters. The act of letter writing is also a way for Khalid to come to a resolution in the exhibition. Mrs Sima is a series of letters to Khalid’s grade school teacher that starts by criticising her for forcing him to write with his right hand and causing his dyslexia. Gradually, he switches to treating Mrs Sima as a more friendly figure, and sharing with her things that are happening in his life. Throughout the series, Khalid writes to her mostly with his left hand, the writing becoming more legible with practice, and he moves from anger and a sense of injury to kindness and near-compassion. These letters, like the one to the security guard, are left unsent. The opportunity to communicate this exercise to an audience, it seems, is enough of a release.

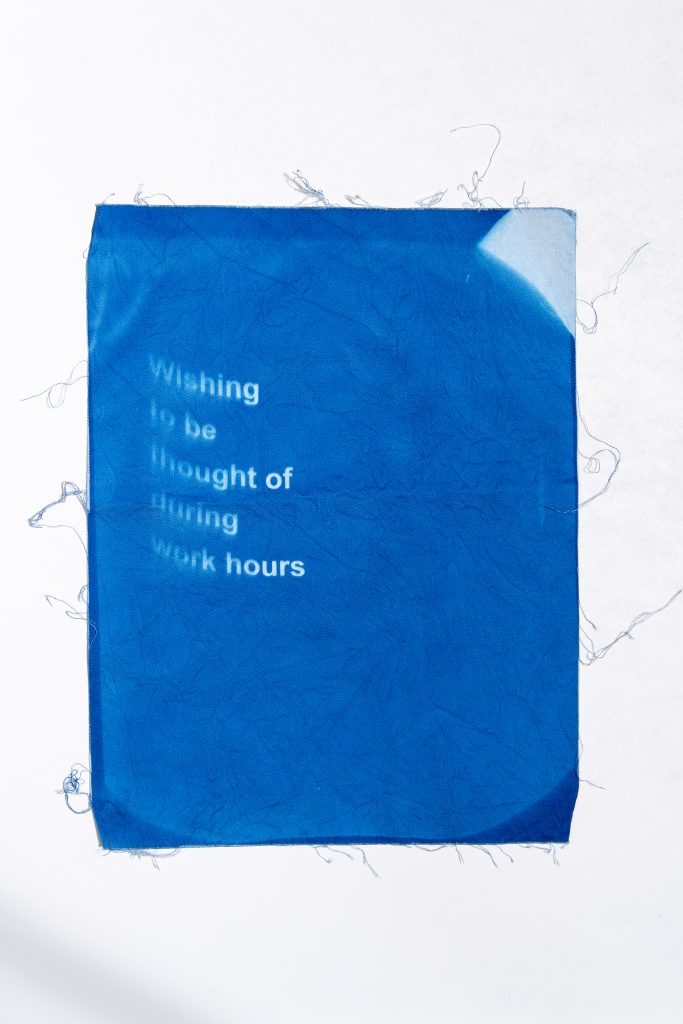

The unsent letters also have to do with who is doing work and why, a central theme in the show. “I don’t want to bring someone else’s labour into my work,” Khalid says. If other figures appear in his artistic practice, it is only as subjects, not participants. For During work hours, Khalid transferred a wide variety of musings to a series of cyanotype-treated textiles during his lunch breaks at his day job with the Sharjah Art Foundation. The pieces range from the obvious (“Thinking about my labor value during work hours”) to the introspective (“Sometimes I am no longer anxious during work hours”) to the lugubrious and political (“Wondering if my passport will ever turn blue during work hours”).

Khalid recalls starting the full-time job shortly before being commissioned for this exhibition, and that the new job had begun to seriously cut into “loitering in the streets and finding experiences”, which he considers his studio time. During working hours was a way to make work by commenting on what he was experiencing in that moment. Not having gone to art school, he also wanted to show that he could still add some physicality to the works, rather than simply printing words on paper. The inspiration for the project was Proposals for Clocks (2016) by David Horvitz, a graduate of Bard College, in which text like “A clock that is wound by the wind” is screen-printed on posters.

When Khalid first began to wander the streets of Dubai, it was to get out of his house at a time when he wanted to feel alone. Wherever he went, stray cats often approached him, rolling around on the ground at his feet and asking for attention. Unemployed and an artist, he thought that in these moments of driving, cycling or running around Dubai, perhaps he would become an expert in his small part of the city, but the cats seemed to have beaten him to it. “These cats had probably been there for years and know more than I ever will,” he says. So in Cats, Khalid draws them, preserving a record of their existence, if not their knowledge of the neighbourhood, and letting the wisdom they might have come through in delicately written phrases at the bottom of each portrait.

“Allah does not burden a soul with more than it can bear” is inscribed below a portrait of a kitten cutely squinting into sunlight. “Don’t mind me, I am just half my father,” is the forbidding caption to a blurry outline of a black feline. Khalid’s personal life is on display at various points in the show in mentions of being “secure mentally but maybe not emotionally” or of an argument with his mother. Yet rather than coming off as juvenile or performative, these details enrich his practice with earnestness.

This is borne out in other projects in Let me tell you something, but it is Flixbus that rounds up the exhibition. In documentation of the budget bus trip in Europe where Khalid forgot his suitcase and attempted to recover it, Khalid realises that Flixbus drivers, like Uber drivers, are hired on a freelance basis and there was no way for the company to know who was driving Khalid’s bus. Two years later, he found a Flixbus driver’s shirt in his local thrift store, which together with a full-size bus stop installation, is presented in the centre of Let me tell you something, a comment on labour and the inescapable nature of precarity in these times.

Central to Khalid’s practice, and what makes it so appealing to look at, is walking, or more accurately, generally moving about in the world. Much of his work reminds us of the potential this most basic of human actions holds to “re-enchant the quotidian”, as Waxman sees her Fluxus subjects having done. Like her flâneurs, Khalid is also alone a lot in Let me tell you something, and there is something enchanting about that, too. Standing at his “bus stop”, it’s easy to imagine being there by yourself in the countryside, the Flixbus having left you without your luggage, and wondering what to make of it when you find a Flixbus driver’s uniform years later.