Ghada Amer’s latest solo show at London’s Goodman Gallery, QR CODES REVISITED–LONDON, plays with a new visual form to revisit the limits of language and meaning.

Celebrated Egypt-born, New York-based artist Ghada Amer is having a cross-continental moment. Four concurrent gallery exhibitions of solely her work are being shown in New York, London and Valencia (Spain) right now, just on the heels of Amer’s three-venue 2022–23 retrospective at MUCEM in France, which displayed her work across different media from painting and sculpture to ceramics and garden installations. Presented in London at Goodman Gallery is QR CODES REVISITED–LONDON, which brings together some pieces from earlier in Amer’s career, alongside fresh appliqué works on canvas.

The umbrella theme for the Goodman show is the role of text in Amer’s oeuvre. For just over decades, from the 2000s till now, text and language have been significant elements in her visual vocabulary, melding into and becoming her figuration and imagery itself, while still being deployed as signifiers of meaning in their most traditional sense. QR CODES REVISITED–LONDON is a relatively small exhibition but deliberate in its focus on exactly that: how Amer has manipulated and machinated “words” in her artworks as much as a QR code reveals meaning behind an encoded link for a “viewer”.

Older artworks are found on the top floor, where four 2007 pieces from Amer’s Definition painting series, which began in the 1990s, are placed in a row. Each painting explores a particular word’s meaning in Arabic – “Freedom”, “Love”, “Security” and “Peace”. The works half-dissolve the script in falling rivulets of paint in pastoral shades of cream, light yellow and eggshell white. According to the exhibition press release, these works show how the weighty word-concepts explored in each work are intended to suggest their integrality to Arab societies, perhaps challenging Orientalist assumptions that they are not.

This is certainly one interpretation, but the particular form of these Definitions paintings also gestures at more abstract analyses, whereby the mere fact that the words are obscured and sanitised, even whitewashed, in tear-tracks of paint raises the question of how opaque and unreachable our own conceptualisations of “freedom” or “love” are. That our social constructions get in the way of, or even blind us to, a still out-of-reach utopic purity that a word like “peace” represents, depends on the gaze and its position. An added layer of distance from meaning appears to those who do not understand the Arabic language.

The floor’s standout however is the wall installation Barbie Loves Ken, Ken Loves Barbie (1995–2002), being shown for the first time in the UK. It’s a fitting time, with the 2023 summer of Barbenheimer just behind us and the subsequent revival of the doll’s narrative, plus all the feminist debate that it has been stoking. The work consists of two life-size straitjackets with the title in French embroidered on them repeatedly in thread as red as a cut. Hyperallergic this year cited this artwork as one of the earliest critiques of Barbie, highlighting how the outfits are technically genderless “onesies”, yet here Amer transfers Barbie’s insane doll proportions onto one straitjacket so it becomes immediately obvious who is Barbie and Ken in these garment-shadows of fictional characters. The critical, playful insouciance of the work not only clangs with the contemporary cultural moment but also serves as a great segue to Amer’s newer works on the floor below, while also highlighting the long history of a specifically Arab feminist, radical undergirding to the artist’s thematics.

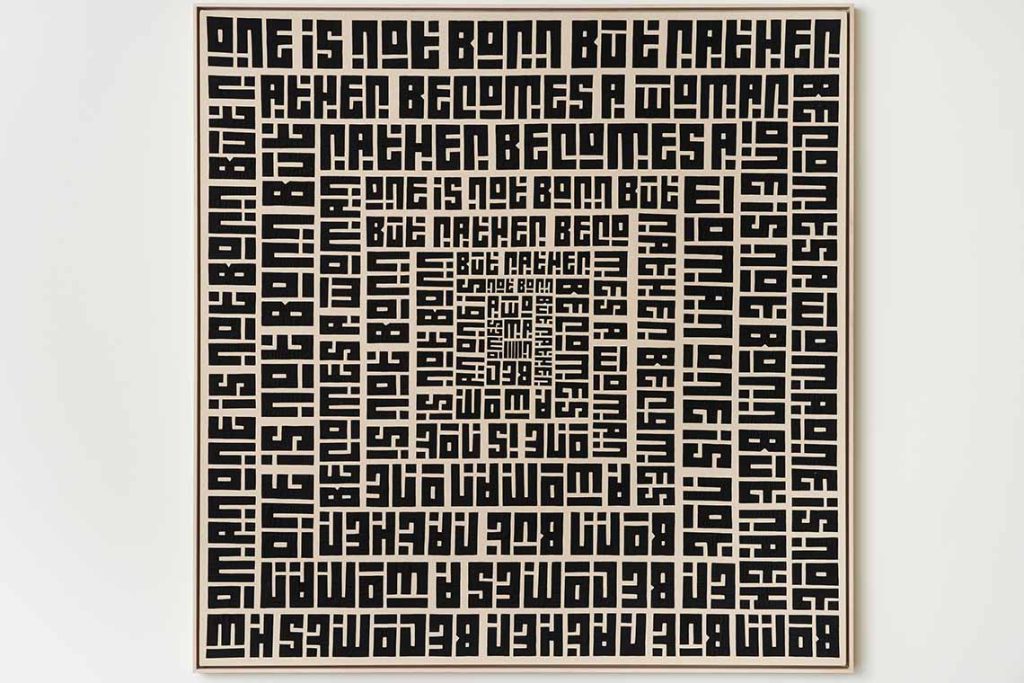

Ghada Amer. ONE IS NOT BORN. 2023. Cotton appliqué on canvas. Framed: 204.7 x 207 cm

The show title’s meaning flowers in full force with a series of 2023 abstract appliqué works that look like giant, enlarged QR codes, and with the exhibition’s wall text only “appearing” now at the supposed mid-point of the viewer’s physical journey through the show. QR codes have already replaced countless paper menus and price lists and are quickly becoming unavoidable. Amer approaches them as a form, a new burgeoning visual language, and one that encodes meaning in a box to reveal more – much like a painting. In these bold, high-contrast, frequently geometric works which she travelled back to Egypt to produce, Amer places text, either in English or Arabic: quotes by the likes of Simone de Beauvoir (“one is not born, but rather becomes, a woman”), Amina Sboui (“my body belongs to me and it does not represent the honour of anyone”), and others.

There’s a slight giddy, galvanising feeling, akin to reading a great zine, that comes with encountering a selection of potent quotes, and to see them rendered so strikingly feels good to soak in. You can walk backwards and forwards to alter your distance from the works, like when you might be looking at something Pointillist, and see a QR code blur into something rousing and poetic. However, slightly disappointingly, the show elides any tackling of the capitalist system, within which any revolutionary must resist their own enmeshment, that the QR code, mostly a symbol for commercial transaction, evokes. QR CODES REVISITED–LONDON is not a vastly new direction for Amer, yet a formally interesting extension of it.