Dima Srouji assembles a cosmogram of Palestine that unsettles Western mythologies of the Holy Land, framing craft as an act of resistance and remembrance amid colonial oppression.

In the Western imagination, Palestine – the Holy Land – has long existed as a subject of projection, romanticised in art and theology as a geography of miracles and ruins. While its image has been endlessly reproduced across myriad media, representations abstracting its physical and political realities have come to eclipse its own material and social truth, thereby failing to reflect the realities of those to whom the land truly belongs.

With her exhibition A Cosmogram of Holy Views, Palestinian artist and architect Dima Srouji approaches those inherited dissonant representations to unpack the fractures it produces. On view at Ab-Anbar Gallery in London, the show poses “a re-presentation and reorientation of what ‘Holy’ means to Palestinians today,” as Srouji says, to generations who have lived through decades of a violent occupation that has rendered geographies, people, artefacts and stories destroyed or displaced.

A way of reclaiming this heritage and challenging erasure, her archival approach intertwines with the personal as she brings together fragments of her motherland. Their sensorial assemblage is posed as a way of thinking through these losses to colonial extraction while rebuilding an image of her home – framing the sacred as something cherished, lived and embedded within spirit, body and land.

These tensions underpin the show’s thematic contemplations, beginning with the series Sacred Dissonance (2025). In these glass collages, Srouji juxtaposes industrial glass panels bearing religious imagery such as biblical landscapes and iconography with smaller, hand-blown panes containing photographs from the artist’s own archives. These more personal montages, obscured by their monochromatic hues and the layers beneath, illustrate the realities of contemporary life for indigenous Palestinians; in one we see her parents wearing gas masks, and in another a view of a dried-out dam revealing remains of cars seized by Israeli forces.

The dialogue between personal and collective histories continues in the following spaces, which take on more spatial narratives in a reflection of Srouji’s architectural background. At the centre of the following room sits a Model of a Sacred Home (2025), a sectional reconstruction of her grandparents’ house in Nazareth, built using the same mother-of-pearl technique once reserved for modelling churches in Bethlehem. By transposing a devotional craft onto a domestic structure, she dissolves the distinction between the monumental and the everyday, turning the middle-class home into a site of reverence simply because of the lives and memories it shelters.

Surrounding this, the walls are mounted with the Anointed Shrines (2025), a group of carved, iridescent structures that draw from those in Srouji’s grandmother’s home, where she would often place a lit candle. In its repetition, this fond memory of a ritual – which neither Srouji nor her family will likely be able to perform again in the same place – sustained a sense of the sacred, independent of institutions. It also became the point of departure for Srouji to reimagine the niches that once housed relics in Palestinian churches, but were looted of their artefacts to be relocated to Western collections. In their place, she installs limestone vessels associated with purification rituals, invoking renewal through symbols and materials that persist.

These bodies of work, alongside an interactive passage laying out the archival materials that guided Srouji’s research process, are punctuated by slower atmospheric moments that invite collective mourning for the lost land, people and stories. Assistant curator Zeynep Koksal describes these rooms as “chapel-like” pauses that shift the exhibition from material to corporeal registers.

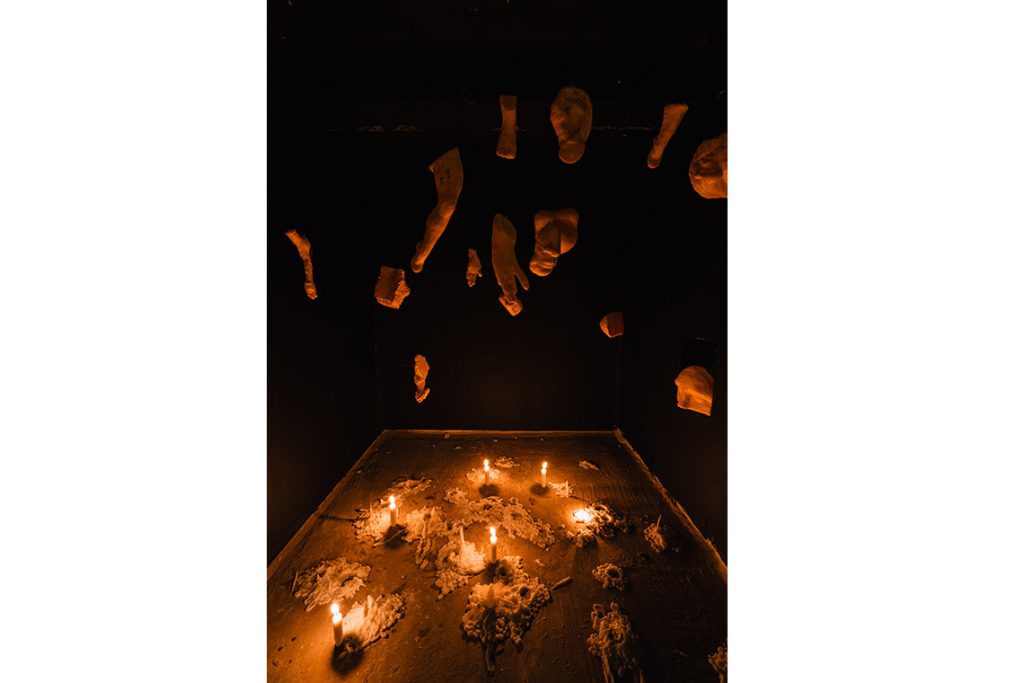

Here, Phantom Votives (2025) is particularly haunting, a sensorial installation that intensely confronts the more violent impact of Israeli occupation in Palestine. Conjuring a reflection on sacredness as temporal and holding form against the unfortunate inevitability of loss, it is a play on the idea of religious votives that are traditionally offered in hopes of healing. Instead, the work memorialises the innocent lives lost in the ongoing genocide in Gaza. In the darkness of the room, beeswax casts of dismembered hands and feet (images we are all now too familiar with through our screens) are hung above flickering candles and engulfed in an equally moving soundscape of chiming church bells.

Srouji’s pride in the crafts and rituals that have endured, despite the occupation of the Holy Land, is key to her resistance as a Palestinian Christian and the reclamation of her heritage. In dissolving the dissonances of perception and reality, her concern with materiality in particular, and the centuries of geological and cultural histories it so deeply carries, becomes most important. Through a palette drawn from the land itself – stone and mother-of-pearl models, ghostly glass vessels honouring the region’s ancient traditions – her Cosmogram of Holy Views reopens sustained indigenous knowledge systems that the colonial regime continually seeks to suppress and deny, reinscribing them as sacred.