Fakhri El Ghezal explores the act of returning home in his exhibition Returns, curated by Hela Djobbi at 32Bis in Tunis.

Located in the heart of downtown Tunis, 32Bis is a multi-storey cultural space surrounded by neighbourhood eateries and the workshops of local artisans. On the evening I visit for the opening of Fakhri El Ghezal’s show Returns, the space is thronged by lively groups of people.

Most of the guests have already visited the space, so the entrance is empty when I arrive. A white map punctuated with a handful of destinations greets me first. Tunis and Akouda are marked at either end of the map, the former where El Ghezal currently resides and the latter his hometown. Softly curving grey lines join various pitstops together, the routes tracing a journey that El Ghezal took whilst documenting the return of his friends to their hometowns. Curator and director of 32Bis, Hela Djobbi, continues this theme throughout the space; calligraphy etched on the walls signals the location of each photograph series and the progression of El Ghezal’s journey.

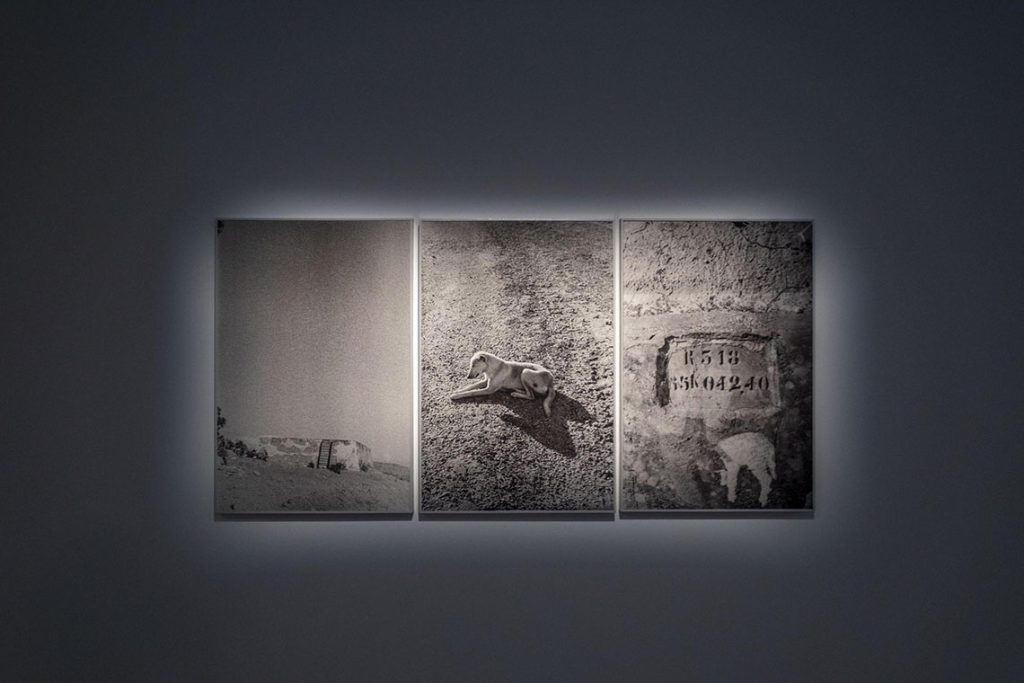

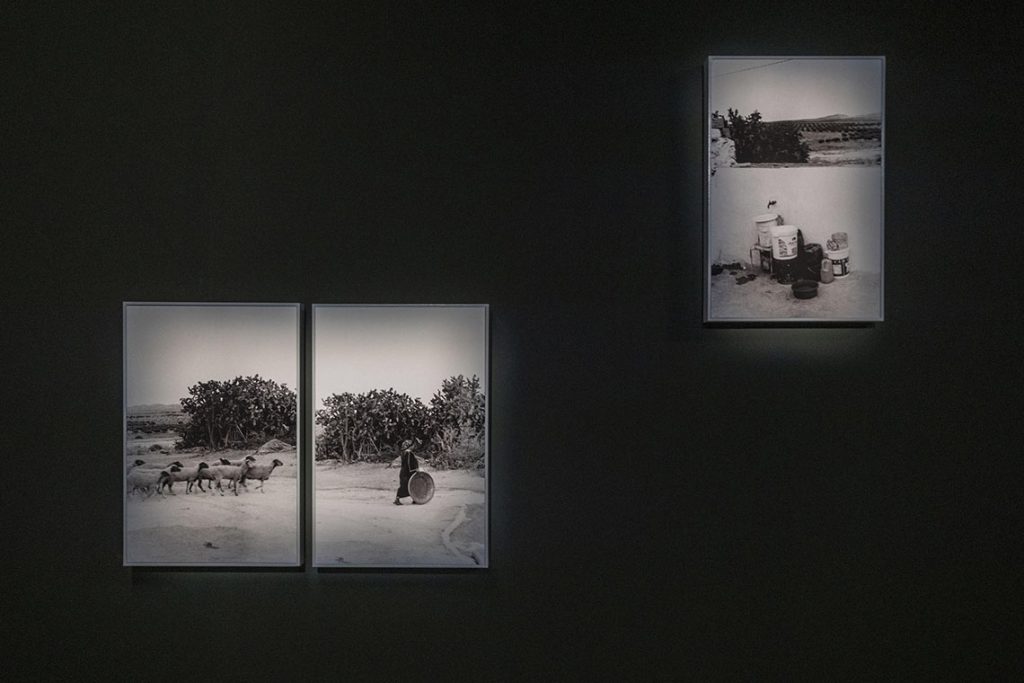

Although El Ghezal explores the theme of return by following his friends’ journeys, these characters are omitted from his pieces. Instead, the viewer is encouraged to piece together aspects of the trip through landscapes, architecture and the occasional image of a person encountered along the way. In some images, the theme is immediately obvious; dirt roads and winding paths lined with trees converge in the distant, eliciting the excitement so often felt when cruising along the open road. The theme presents itself more subtly in other places. One image evokes the theme of travel through a parked motorcycle whilst another captures the movement of a flock of birds. Their migration, aimed straight towards the viewer, suggests an innate and seasonal urge to return.

In other photographs, El Ghezal cleverly nods to the theme of ancestral homeland. An image of a Tunisian flag is placed next to a picture of a rosary hung on a wall and a hand painted ceramic bowl. Inscribed on the bowl is a personal message, “to my mother Beya, the best of all the people”. An image of an older man looking off to the side completes the untitled set of four, with the objects surrounding him in a smaller format in order to convey their belonging to this patriarchal figure. Other pieces create a similar sense of ancestral intimacy, depicting the courtyards of homes and farm animals. Through these photographs, El Ghezal captures the familial spirit of these homelands.

Interestingly, the plural form is used in the exhibition title. This seems to allude to one of the most evident questions raised throughout the show: why do people return? The theme of visiting loved ones is occasionally evoked by photographs of young children, their arms wrapped around each other or outstretched, as with one young boy balancing atop a building. In aged plastic chairs, old figures lounge with salt-and-pepper tinted bristle beards and glittering white hair. These figures, candid and rarely looking at the camera, are both personal and anonymous all at once. As I look at them, I occasionally interpose figures from my own life, familiar faces suddenly merged onto blurred forms or turned heads.

In an untitled series of two particularly thought-provoking images, glittering white headstones and rectangular tombs lay peacefully under the dappled shade of an overhanging tree. The seemingly tranquil stills nod to the sombre act of visiting your hometown in order to attend a funeral or to be buried there yourself. In a far more overt image, a lamb has been slaughtered. Blood stains lining its coat and smeared across the floor suggest it has been sacrificed, as is common during Eid. Suddenly, we are reminded that often journeys are made in order to enjoy celebrations with loved ones, so it seems that – whilst the destination remains the same – the reason to return is ever-changing.

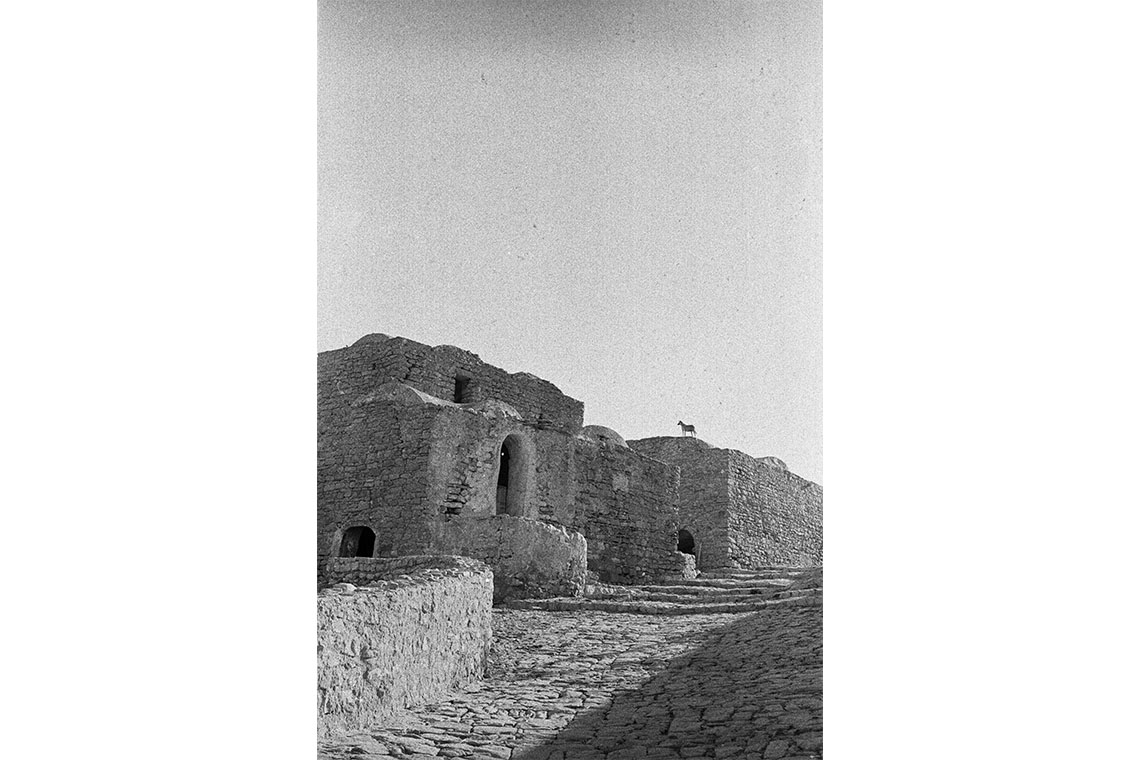

Particular focus is paid to historical architecture throughout the exhibition – I catch sight of soaring columns and humble stone dwellings. Each construction incorporates design aspects of various styles, with white-washed cupolas typical of Islamic architecture displayed next to timeworn waterway systems built by the Romans. In other images, the buildings and their surroundings are contemporary. Metal transmission towers and streamlined concrete establishments stand in stark contrast to the cobbled streets on which they sit. It seems by documenting the diverse architecture across the region, El Ghezal is forcing the reader to recall all those who have journeyed across it. Colonised by the Phoenicians, Romans and the French, the land has been repeatedly occupied. Who exactly has the right to return today?

Towards the end of the show, an illuminated cabinet displays unused negatives taken during El Ghezal’s journeys. Visitors are able to peer at them using a magnifying glass, making out faint trees and miniature figures through the plastic film. The display encourages the viewer to consider the aspects that have been omitted from the exhibition. I start to think about other parts of a return journey that one might expect to see; the excited preparation to embark on a trip; the warm embrace of those who welcome you; tables full of food lovingly prepared by those awaiting your visit. By intentionally leaving out aspects of the return journey, El Ghezal cleverly creates a void for interpretation. I am left wondering what I would expect to see when returning to the places I have called home.

Returns runs until 28 June