The curatorial debut of studio salasil with their group show at Bayt AlMamzar is an invitation to ponder on the past without dwelling on it, and to allow our shared histories and hardships to inspire us to imagine a more hopeful future.

Crystal Clear, currently at Dubai’s Bayt AlMamzar, acknowledges that it can be difficult sometimes to know what to make of the times we live through, let alone to imagine a future wrought by them. This first offering from curatorial duo studio salasil invites artists to disrupt tensions and look past preconceived notions in an attempt to understand what to do when the future is anything but crystal clear.

If there is a tendency to see the world we inherit from previous generations as one that’s more messed up, we’re probably not looking at the data. Against the backdrop of the conflicts and strife that define every age, Oxford’s ‘Our World in Data’ tells us the world is definitely not as bad as you think. Well-being indicators like life expectancy, child mortality and extreme poverty, for starters, are better than they have ever been, all as the global population has increased dramatically.

But Crystal Clear reminds us that often what matters most to us is stories. When colonisation has stolen stories of the past, war is contaminating our present stories and climate change slowly erasing the future, what stories are we left to imagine?

“We originally wanted to talk about the future in terms of dreams and how we can make it our own,” says Zainab Hasoon, one half of studio salasil along with Sara bin Safwan. After months of working with artists to decide what to include or what new work to commission, “7 October happened and everything just stopped,” bin Safwan says. “We had been talking about the future for so long and discussing these big ideas, but were suddenly zeroing in on a very specific moment and asking how can we think about the future when it seems so uncertain, so … unreachable.”

From that point, the show became a way to confront the present, in part by envisioning an alternate future. In works ranging from video and sound installation to painting, sculpture and works on paper, there is a distinctly Palestine-focused energy. Amad Ansari collects Palestine-related websites archived by the Wayback Machine. In Palestine Online, Palestinian contemporary art websites share space with sites about martyrs and other platforms in line with Crystal Clear’s thesis.

Works by Dima Srouji command the normally cozy former living room at Bayt AlMamzar, a home converted into an independent community space, gallery and studios. The work’s satellite images show before and after photos of obliterated Palestinian neighbourhoods, as well as pixelated areas where Israeli settlements were made obscure to satellites, according to the United States’ 1997 Kyl-Bingaman Amendment. In what is an elegantly concise and readable history of occupation, oppression and destruction, Srouji looks where we cannot see, calling to mind the photos of secret CIA prisons by which Trevor Paglen made his name.

A selection of the paintings that Rami Farook created daily for months after Israel’s October 2023 invasion of Gaza are inspired by headlines and social media posts. The crudeness of Farook’s sometimes hasty compositions parallels the foul events portrayed. Paired with the drawings are a sort of diary entry listing snippets from social media that tell the story of each day’s horrors.

Other works more explicitly imagine futures, acting as conduits for hope or, in the case of Ali Eyal’s huge painting-within-a-painting, fantasy. A pair of hands appears to tear (or put back together?) a psychedelic painting of a parade of Wonderland-esque characters and scenes. Palestinian architect Sara Bokr’s collaborative work The Material Fabrication School of Gaza (2024) collects her renderings of a building to house the school along samples of alternative building materials developed by four designers that could potentially be created within the school. A concrete substitute made from date seeds, for example, avoids Israel’s ban on certain construction materials. Similar to Khalil Rabah’s Palestinian Museum of Natural History and Humankind, Bokr hovers between art and public platform, deploying the former to imagine the design for anti-oppression solutions.

Shows having to do with how artists might visualise the future are having a moment, in the UAE and beyond. In an exhibition at Abu Dhabi’s 421 last year, curator Ritika Biswas looked at the potential for the end itself to be a site for something new to begin, while an episode in MoMA’s Circular Museum podcast about art and climate change was called ‘Representing and Implementing Alternative Futures’.

But Crystal Clear keeps it real, acknowledging that any way of thinking about the future, including hope, must be informed by the past. Haneen Sidahmed’s video installation gathers newsreel clips from the several revolutions that have marked Sudan’s modern history. They document the hope for change that the country’s largest ever social movement brought in 2018 and its failure to deliver the transformation for which it strove.

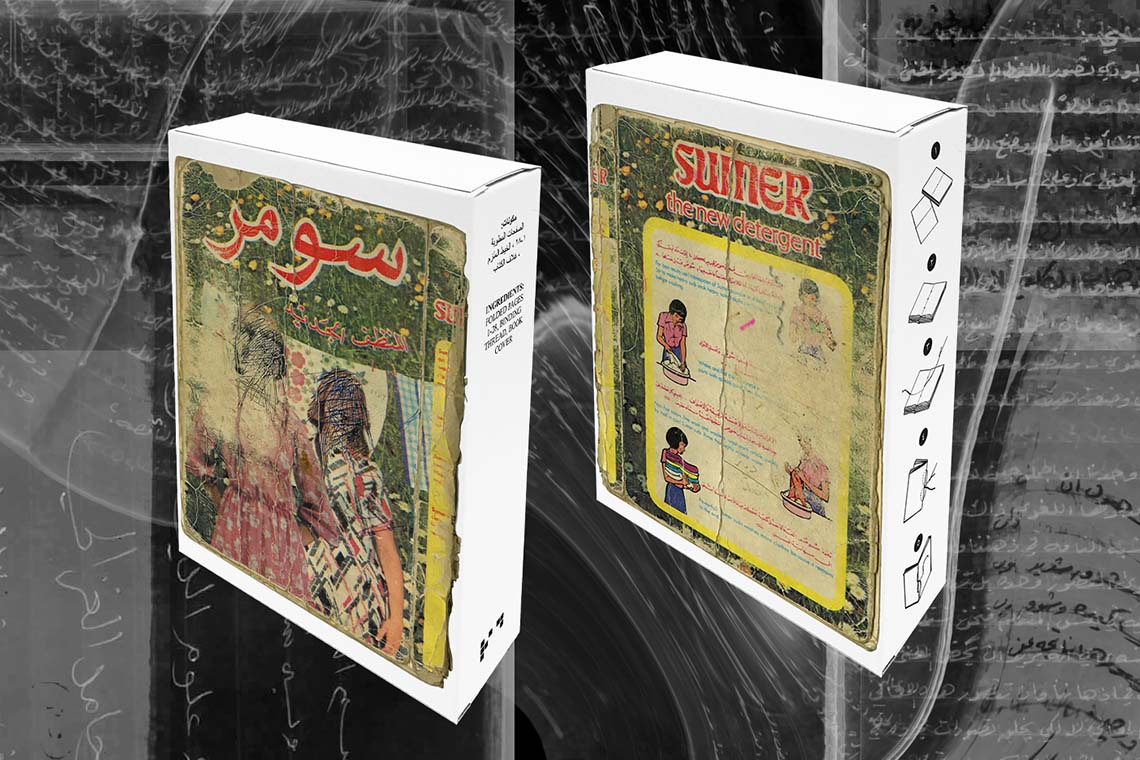

A striking artist book by Ahmad Makia stands apart in the exhibition. Sumer: Self-publishing in Abu Ghraib Prison (2023) is based on an archive of self-published underground books made by political prisoners in Abu Ghraib during Iraq’s Baathist reign in the 1980s. The book is a collection of scans of extracts from handwritten copies of books by Iraq’s opposition thinkers and intellectuals – books that were banned both in and outside of the prison. When purchased, Sumer arrives in pieces to be assembled by the purchaser, paying tribute to the pains taken by prisoners to disseminate knowledge as contraband. In any future where we move forward, Makia seems to say, recognising the work done by those who precede us is a crucial step.

Crystal Clear runs until 11 May