The latest edition of the Liverpool Biennial honours the foundational elements that make the city such a dynamic hub for history, art and culture.

For those of us who grew up in London, the city of Liverpool has always been synonymous with football, conjuring up images of passionate clashes between fans of the two rival teams that call the city home. Yet football is not the only thing underpinning this multi-layered city. The theme Bedrock, chosen by Marie-Anne McQuay, curator of the current Liverpool Biennial, is as much a metaphor for the socio-cultural foundations of the city as a nod to the sandstone on which the city rests and from which many of its buildings are made. McQuay’s deep appreciation for Liverpool’s many layers shines through at every turn of the biennial, reflecting her desire to showcase its “complex global history, as a port city of empire at the heart of the transatlantic slave trade, and its vibrant and resilient present having come through a period of twentieth-century managed decline.”

It so happens that longtime Liverpool resident McQuay is keenly aware of how deep the love of football runs in the city. Inviting one of the many international artists participating in the Biennial to pay homage to a sport so entrenched in local culture it elicits a form of tribalism amongst its supporters could be risky. Yet Turkish artist Cevdet Erek’s Away Terrace (Us and Them) (2025), a large recreation of a football stadium from earth bricks, taps into the core of the passion that underpins the city.

The venue is an unassuming building in downtown Liverpool, a wide-streeted, warehouse-filled area of the city, reminiscent of NYC’s Brooklyn in style and character. Erek’s installation sits squarely in the middle of the room, skylights illuminating the scene like an indoor sports stadium. Ritualistic music thuds and thumps as I walk around the stadium. The feeling of something impending looms, like the moment just before a gladiator enters the ring – yet that something never arrives and the stadium remains empty. I cannot help but move to the beat of the sound, in the same way that the cheering of the crowd at a sports match can transport and tap into something almost primal within us, uniting and dividing in the same motion.

The idea of ‘us vs them’ is omnipresent throughout the biennial, although it seems that this common experience of estrangement and belonging ultimately unites and serves as the foundation for the city itself. “We are living in such fragmented and fragmenting times, and always in the shadow of empire, that the sense of grounding through the familiar, through what can be passed on and cherished, resonated strongly for so many of the artists in the biennial,” observes McQuay.

This theme of fragmentation is part and parcel of Liverpool’s history, variously along religious, ethnic or cultural lines. The emergence of a new Catholic identity in the city, following waves of Irish and Italian immigration from the nineteenth century onwards, forever altered Liverpool’s demographics. The effect of such migratory patterns on architecture is explored in artist Elizabeth Price’s HERE WE ARE (2025), screened in a pitch-black room in Chinatown. What unfolds as an inquisitive conversation in typed text on the screen over images of modernist Catholic churches built from modest materials (the antithesis of what is typically associated with Catholicism in its more exuberant expressions) transforms into a probe into the psychological implications of architecture. As music crescendos throughout the film, Price delicately leads us to understand the migratory experience in the face of an unpredictable post-war world, ultimately demonstrating how these modernist churches physically carved outa place for Catholic migrants in the twentieth century.

Image courtesy of the artist and the Liverpool Biennial

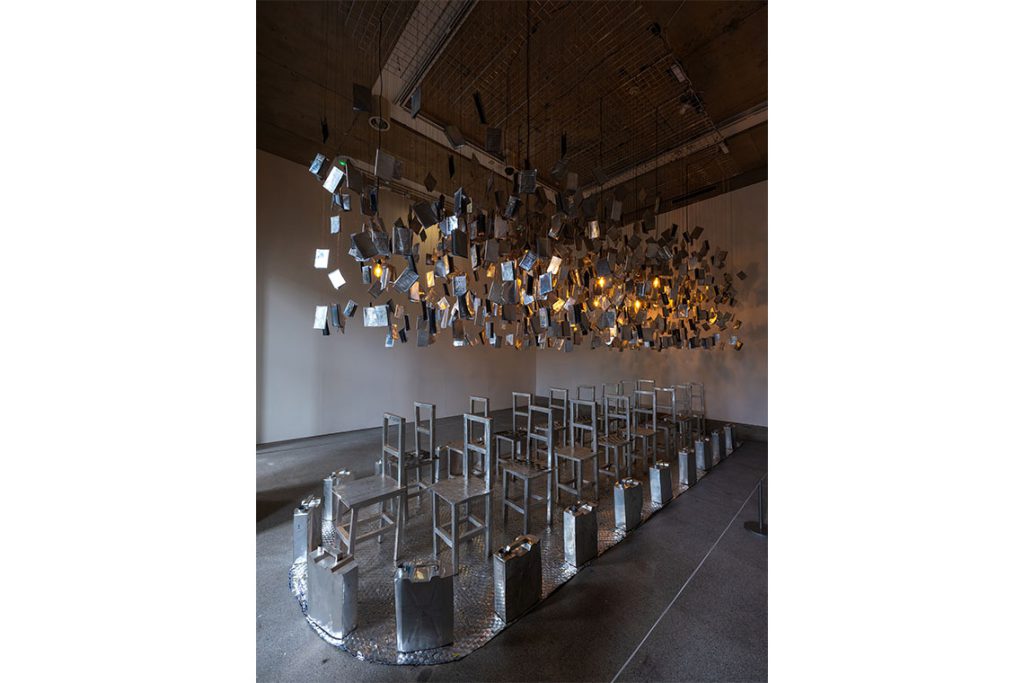

Another, more disturbing, aspect of the migratory experience is presented at the contemporary art centre The Bluecoat, where Ugandan artist Odur Ronald addresses one of the most uncomfortable yet foundational episodes in Liverpool’s history: its central role in the transatlantic slave trade. A series of aluminium passports hangs over an arrangement of chairs representing the infamous Brooks, a ship used to carry thousands of enslaved peoples across the ocean. What sounds like a deliberately muffled conversation unfolds over a speaker and the lights flicker over the installation. The atmosphere suddenly shifts, as we wait in a state of suspense, echoing the experience of migrants waiting for their next steps. Ronald’s second work in the biennial is in the most unlikely of venues. In Seven Store HQ, amongst rows of other shoes on sale, a pair of silver sneakers sits casually. Here, the artist appears to break free from the constraints and expectations of the contemporary art world that keeps migrants in a perpetually held back state, if not from society as a whole.

The unexpected recurs in the Liverpool Biennial in even the most traditional places, as with the Walker Art Gallery, renowned for its extensive art collection dating from the thirteenth century to the present day and which is hosting several of the biennial’s artists. Among them, Canadian-Lebanese artist Nour Bishouty’s Nothing is lost except nothing at all except what is not had (2025) takes over almost an entire room dedicated to the biennial, with another sculpture on display within the permanent collection. Bishouty, whose multimedia installation takes as a starting point a painting by her late father Ghassan Bishouty, reflected on the duality of the museum setting: “It is deeply moving to me to see my father’s work in a museum, despite the violent and inherently colonial nature of museums”.

Photography by Stuart Whipps. Image courtesy of the artist and the Liverpool Biennial

Along with fellow Lebanese artist Mounira Al Solh, whose series I Strongly Believe in Our Right to Be Frivolous (2012–) is displayed in the Tate Liverpool’s temporary location at RIBA North, Bishouty interprets the theme of Bedrock from her own experience as an artist hailing from lands historically exploited by the ideals that helped found Liverpool. “My mother is Palestinian Jordanian, my father is Palestinian and Lebanese,” she explains. “This understanding of being dispossessed in my own land in the same way my ancestors have been connects very directly to this concept of bedrock in the way Marie-Anne understands it.” Her carved sculptures of elongated farm animals look like they could have come straight out of any one of the pastoral paintings in the nearby galleries, perhaps indicating that certain foundational elements, namely the impulse to record and retain legacies, remain the same – no matter where we come from.

The Liverpool Biennial works best when it does what it says on the tin, when it is most firmly embedded in the bedrock of the city, whether that be quite literally in landmarks or less obvious locations such as Chinatown or a local pharmacy. Liverpool, McQuay emphasises, is “a place where histories and cultures collide, a city formed from migration and immigration”, a place that people whose commonalities may not be immediately apparent now call home, with all of the richness and chaos that entails. My only regret upon departing the biennial was that the art circuit did not end in another foundational Liverpool location, a local pub, but perhaps next time.