The winner of the fifth edition of the Richard Mille Art Prize highlights the value of spaces and silences through his practice.

Creating work since the early 2000s, Japanese audiovisual artist and composer Ryoichi Kurokawa is considered a trailblazer on the audiovisual art scene. Embodying distinct aesthetics derived from his synesthetic abilities, the axis of his practice revolves around capturing natural phenomena with technological systems as a primary tool of making. In Kurokawa’s synesthetic mind (wherein one sense involuntarily triggers another), images and sound are produced simultaneously as a unit: images have sound and sound emits light, ideas usually realised directly onto software. These are the seeds of his multisensorially immersive installations and live concert performances, meticulously orchestrated to create holistic physical sensations that stimulate the mind.

Living and working in Berlin since 2010, Kurokawa did not initially intend to professionally pursue an artist’s life. It was, at the outset, a pleasurable activity shared with peers. “I began creating computer-based graphics in the late 90s during my student years, and this practice gradually and naturally expanded into the creation of sound,” he says. “Through hands-on experimentation with various [technological and digital] tools and the exchange of knowledge with friends, I acquired technical skills in a manner that felt like an extension of play,” he adds. The knowledge barter with his peers forged an acceleration of his upskilling in place of formal training in art and music.

Image courtesy of Richard Mille

Being born in the outskirts of Osaka in Japan has in part influenced the artist’s affinity to nature and his instinctual outsourcing of his artistic inspiration to its phenomena and systems. “The primary source of inspiration in my practice lies in nature,” he explains. “I’m especially drawn to what becomes visible when natural materials are broken down and rebuilt. By deconstructing nature and then reconstructing it, hidden depths and unexpected new forms emerge. This process of re‑creating nature is an endless source of discovery in my work.”

In particular, Kurokawa has developed a fascination with the entropy of nature: its irreversible tendency to shift to randomness, disorder and chaos. In his audiovisual concert subassemblies (2019), he contrasts nature’s entropy with artificial structures (ie. architecture and the urban environment), created by humans to resist this flow and introducing temporary order. He captures both nature and man-made realities using laser-scanning technology, gathering spatial and colour information from the earthly realm as three-dimensional data. Field-recorded sounds, an integral characteristic across Kurokawa’s works, are digitally processed and mixed with computer-generated audio. Within the 45-minute performance, the abstracted and artistically manipulated data are re-organised in a new spatio-temporal timeline, coalescing sound, images, light and space into a multisensory experience for the audience to encounter as a cinematic sensation.

Beyond his installations, Kurokawa’s interest in natural systems and technological media is also realised into sculptural form, as in his 2018 works elementum and Ittrans. elementum layers the Japanese technique of oshibana (the flat pressing of flowers and plants) with digital printing, exhibiting butterflies, flowers and plants, neuron-like constellations on plinth vitrines. In lttrans, a series of digital diptychs is derived from 3D digital analysis of real plants, producing halves that are antithetical to each other: one in fragmental chaos and the other in structural order. Beyond an intricate system worth prodding in his artistic work, nature for Kurokawa is also a place of respite. “It is not only an essential element of my artistic practice, but, beyond the realm of art, a fundamental presence that continues to offer me moments of insight and serves as a catalyst for reflection and action,” he reflects.

Foundation for Art and Creative Technology (FACT), Stereolux and University of Salford Art Collection. Co-produced by FACT, Stereolux,

University of Salford Art Collection, Arcadi and DICRéAM. Supported by CEA Irfu, Paris-Saclay (Alternative Energies and Atomic Energy

Commission / Institute of Research into the Fundamental Laws of the Universe). Produced by Studio RYOICHI KUROKAWA

© 2016 RYOICHI KUROKAWA

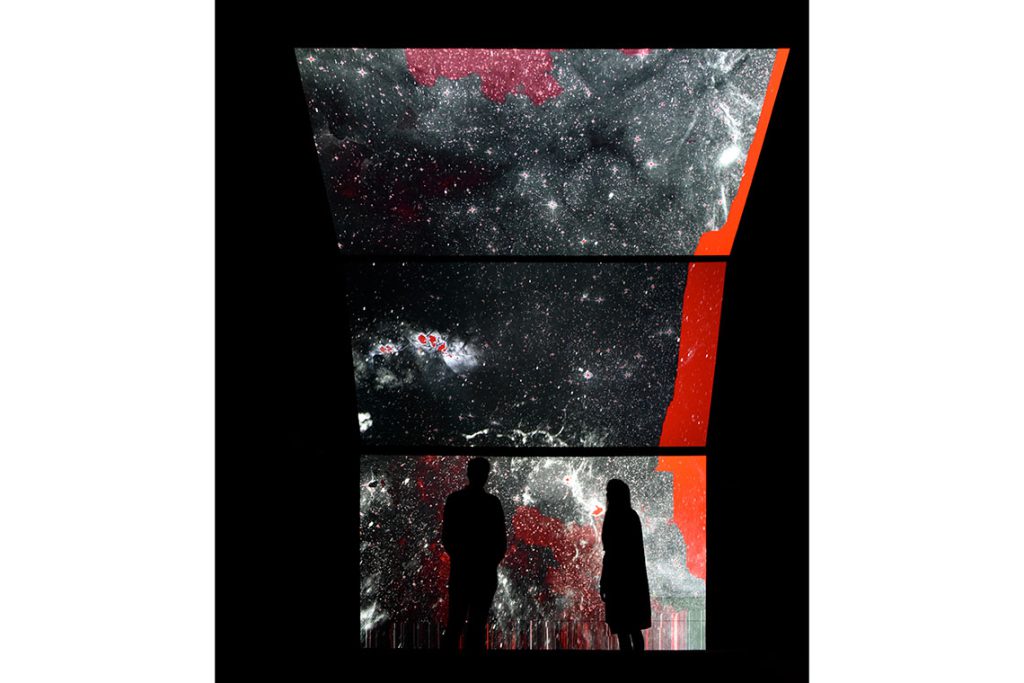

Scientific collaboration is also an integral paradigm in Kurokawa’s practice. In unfold (2016), he collaborated with an astrophysicist to capture celestial data from space telescopes in order to understand the cosmic history of the Sun over billions of years. What results is an immersive installation that transports the audience sensorially into space, with Kurokawa visualising star formations from the gathered data into a human-scale artistic form. A curved, floor-to-ceiling three-channel screen akin to a planetarium experience is complemented by 6.1ch surround sound, and a tactile transducer transforming his sound compositions into physical vibrations felt from the installation’s floor. Here, the “feeling and experience of the universe” is transported to Earth. For Kurokawa, the experience of his installations is inherently distinct from his audiovisual concerts. “Many of my installations are structured as loops without a defined beginning or end, allowing viewers to enter and leave the experience at any moment,” he shares, seeing his installations more in a ‘painterly manner’. “Its composition is perceived all at once, and the viewer’s position within the space becomes part of the work itself.”

Kurokawa’s work is highly influenced by significant concepts in Japanese aesthetics and culture, particularly the concept of ma (interval). “It does not simply mean ‘negative space’. Rather, it refers to the aesthetic value of the intervals that arise within time and space,” he interprets the philosophy. “In spatial terms, ma is not mere emptiness. It is regarded as a presence that arises precisely because it is void. In temporal terms, it manifests as silence or pause, where moments of inactivity highlight the next action or sound. In other words, ma is a uniquely Japanese aesthetic that values the spaces and silences between entities more than the entities themselves.”

Image courtesy of Richard Mille

Winning the latest Richard Mille Art Prize, Kurokawa’s site-specific installation skadw– (2025) at Louvre Abu Dhabi allows ma to shape both its spatial structure and the viewer’s experience. Avoiding a literal approach to the Art Here 2025 theme of ‘shadow’, the artist instead meditated on shadow’s reliance on light to realise its existence. “I composed the space so that light would enter the area enveloped in shadow, allowing viewers to understand, through the presence of light, that they had been within a shadow all along. Light sources and fog are placed at the far end of the corridor, while the rest of the corridor is filled with empty, dark spaces. This seemingly ‘empty’ area is, in fact, an essential part of the work. True to the concept of ma, it is precisely the absence of things that creates a sense of presence. How this emptiness is interpreted is left to the viewers.” He gives his audience agency through deciding their own distance to the light and fog, allowing them to “define their one unique sense of ma”. Aside from the spatial ma, temporal ma is also integrated into the experience: stretches of darkness were intentionally created to amplify tension.

There is a considerable meticulousness and intentionality in the details of Kurokawa’s work: even the Japanese characters of ma itself influence the architecture of the piece: “The character “間”(ma), composed of the kanji for ‘gate’「門」 enclosing ‘sun’ 「日」 depicts sunlight streaming through a gate’s gap. The design of light entering through the slit in this installation reflects this origin.” The artist allows the architecture of Louvre Abu Dhabi and the environmental conditions of the wider city to shape his work. The museum’s semi-outdoor corridor engages with natural light for a softly dim atmosphere in the day, while the night brings an absolute darkness – for Kurokawa this natural phenomena is a particularly compelling aspect of collaborating with the spatial specificity of the museum.

Although every one of Kurokawa’s works is backed by a myriad of collected scientific information, the artist does not see his work as a tool for proliferating information or conjuring scientific advancement. Instead, he views his installations as an altered perception of time. They are portals through which audiences can allow themselves to become immersed in a different vibration of sound and light, and interpret a space freely within their own realities.

This article first appeared in Canvas 122: If Walls Could Talk