Treasured childhood memories inspire the artist as he seeks to make sense of a life punctuated by hardship and the whimsical hand of fate.

Sitting in his studio, far away from his beloved native country of Iraq, Sadik Kwaish Alfraji still remembers his earliest memories from when he was just three years old. They revolve around the most central figure in the artist’s early life: his father. “Many recollections spring to mind. Some were beautiful and some were painful”, Alfraji tells Canvas with a smile, speaking to me from Amersfoort in the Netherlands, where he has lived for nearly 30 years. “I [still] have a foggy image of my father building our house with his bare hands.”

The year was 1963 and Alfraji’s family had moved from southern Iraq to Baghdad, where the artist had been born in 1960. He grew up in the slums of the Iraqi capital, where locals with no income or property of their own lived in ramshackle houses made of basic materials. One day, the government allocated his father a plot of land, populated by a few dogs, donkeys and horse carts but where he was able to build a proper home.

Describing himself as an obedient child but “occupying a weak body”, Alfraji’s early years were tough. He remembers feeling deprived of the finer things in life, including ownership of a bicycle. “In my mind, I still have scenes of myself crying because I wanted a bicycle,” he recalls, “but my family couldn’t buy one for me because it was expensive.” He also did not receive any kindergarten education, since it was a luxury back then and simply unavailable in his area.

Despite – or perhaps because of – the daily hardships, Alfraji was close to his father, who saw something special in his child and always strove to support him. Working as a security policeman at foreign embassies in Baghdad, he brought his son pastel crayons and drawing notebooks, as well as illustrated storybooks that had been discarded by the embassies. Another memory that still lives in Alfraji’s mind is of when his father was adamant about enrolling him into elementary school but lacked some of the papers needed to secure admission.

“I witnessed a scene that I could never, ever forget,” he says. “We were in the principal’s office. He was sitting behind his desk and my father was standing, begging him to allow me to attend class with the other students. The principal completely denied his pleas at first, but the exchange ended with my father moving closer to him, bowing his head and kissing his hand. My father did all of this to keep me in education and I’ve remained grateful to him all my life for that.”

It was at school that Alfraji’s journey with art began. He started by drawing the people and objects around him, later gaining access to more material at high school. He developed a strong passion for reading books and watching movies. His family had hoped for him to pursue a traditional profession such as medicine or engineering, so when he announced his plans to study art, Alfraji recalls how it affected his father. “It was a decision that depressed him at first.”

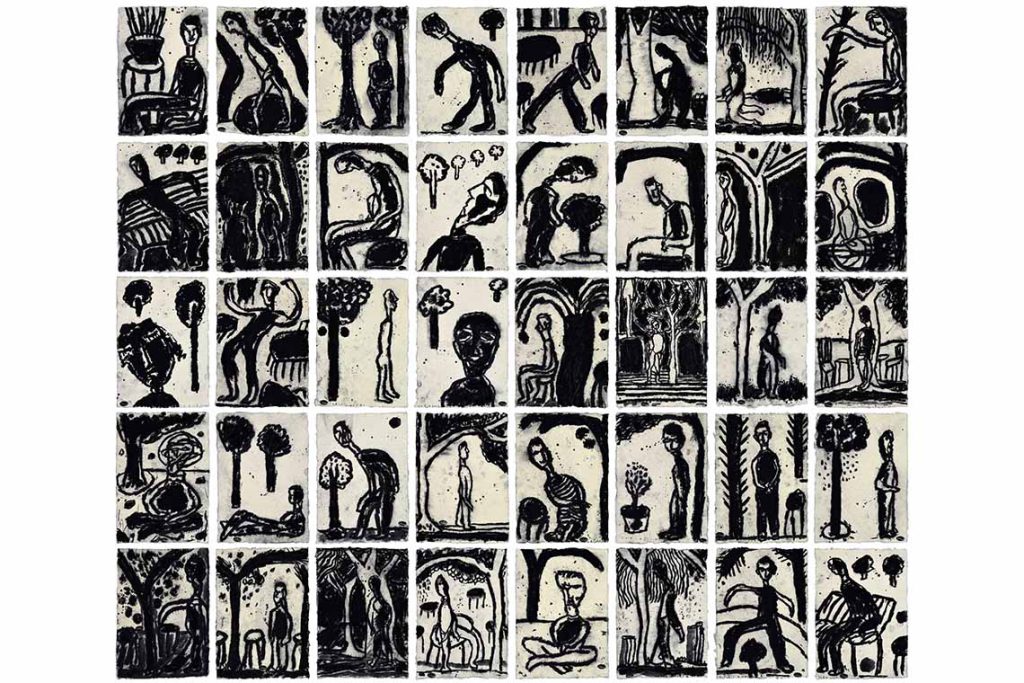

Image courtesy of Ayyam Gallery

However, Alfraji’s teachers spoke highly of his potential and, with his father’s eventual convincement, he went on to study at Baghdad’s Institute of Fine Arts and Academy of Fine Arts during the 1970s and 80s. It was a time, he recalls, when “Sadik was born”. He had a major awakening, influenced by the philosophies of existentialism, Sufism, nihilism and the socio-political woodcut imagery of the German Expressionists – all of which continue to inform his work today.

In the 1990s Alfraji left Iraq, then under the autocratic rule of Saddam Hussein. “The reason why I left? Freedom,” he says. “Life for anyone with a free mind and artistic ambition under a dictatorship was impossible.” He also felt exiled within his own society. “You’re speaking the same language, wearing the same clothes, but you are a foreigner, because your concerns and thoughts are different from those of the other people around you,” he adds. In 1996 he settled in the Netherlands, but is sanguine about a life underlined by hardship. “To be honest, I’ve suffered in my life,” he admits. “I’ve suffered from poverty, social exclusion, living under a dictator and exile.” Such topics have, in one way or another, seeped into his art, which he describes as an integration of emotion and concept. Alfraji’s imagery is executed in a thick-lined, animated manner, and he is known for predominantly using ink and charcoal – materials that he calls his “long-time friends”.

During our conversation, I cannot help but notice the random sketches on the walls behind him. They are all made using black ink, as with the rest of his formal work, without a drop of any other colour. “There must be a psychological reason why I use only black,” he admits. “I have a huge love for it. It is brutal, sharp and direct, and was used by the German Expressionists to show emotion in its most extreme circumstances.” That Alfraji’s work is charged with emotion is undeniable, with much of the energy that drives his drawings and animations being drawn from his own experiences and specifically his early years. “In general, whether you are an artist or not, a human being cannot be separated from their past, including their childhood,” he says. “When we live in the present moment, it is inevitably connected to what has happened before and what will happen after. Therefore the concept of time, which we divide into the past, present and future, is actually a continuous flow in which moments are intertwined, or as the French philosopher Henri Bergson states: Time is a constantly flowing extension.”

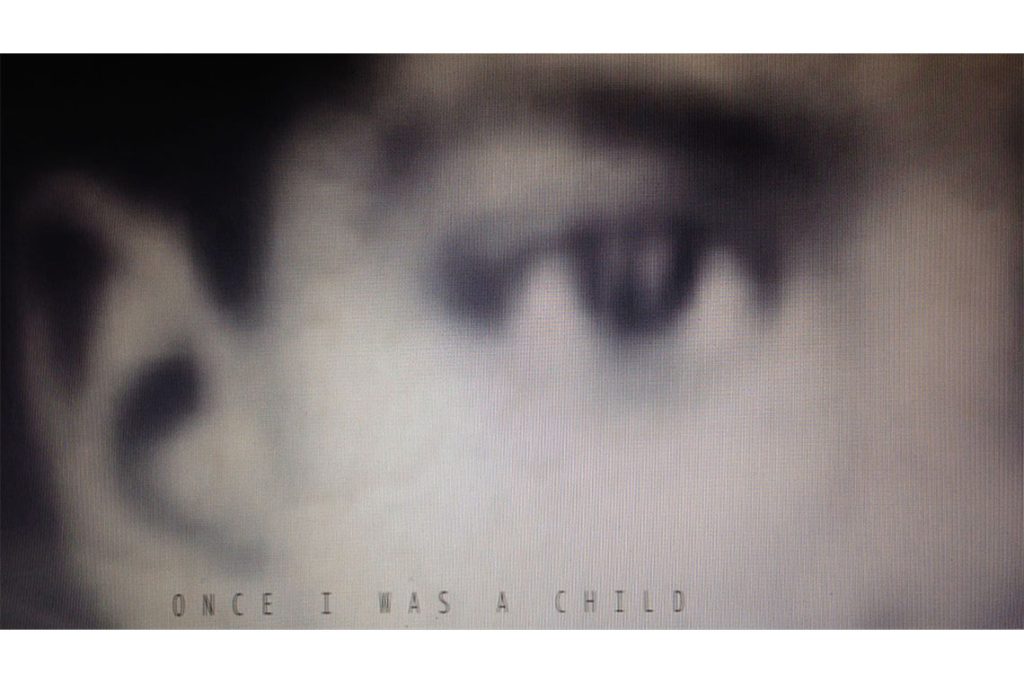

The titles of Alfraji’s works highlight their deeply personal nature, among them Once I Was A Child (2000), The House That My Father Built (2010) and The Tree I Love at Abu Nawas Street (2017). It seems that he is constantly revisiting the places and people of his past. “For myself and others, art is a form of therapy and liberation,” he says, emphasising the enduring nature of the links that he sees as inextricably binding him but which also offer the power of nurture and freedom to express himself.

One of his most profound works was inspired by his 11-year-old nephew, Ali. In 2009, Alfraji made a rare return visit to Iraq, where Ali wrote him a touching letter with a simple drawing of a canoe and the words “I wish my letter takes me to you”. It had a major impact on the artist. “When I have an emotional reaction to any event, a period of time has to pass by for me to know how to deal with it,” he explains. “The letter made me cry and feel ill. I closed it, put it in a book and placed that book on a shelf in my library. Then, I forgot about it. That emotional reaction stayed engraved deep in my heart and mind, but it took years for it to come out. It had to be turned into an artwork with a narrative so that I could be freed from this letter.”

In 2014 he finally made Ali’s Boat, featuring an array of drawings based on the letter. He also created a hand-drawn animated video, where a peaceful (and sometimes tearful) face is surrounded by the emotional heaviness of the passing of time. There is, for instance, an unfolding scene of the board game, Snakes and Ladders, a popular (and affordable) pastime during Alfraji’s childhood. “I was trying to tell Ali that life is not what he imagines it to be,” he explains. “You throw the dice, which dictates your next steps. You are not free in how you move. It’s a game built on the concept of fate and it teaches resilience. It can take you up to the snake’s mouth and then throw you down to the bottom. But you resist by throwing the dice again in the hope of reaching your goal, and that is life.”

There is a universal appeal in Alfraji’s art, for he claims that the human condition is one commonality shared by all, regardless of the viewer’s background. As for how he hopes his work is perceived, “I really don’t know,” he admits. “I like to focus on the narrative itself and that comes from the heart. Until now, I’ve noticed that there was always a strong relationship between the viewer and the work that I make. If my artwork is speaking truthfully, then its effect will be the same for everyone. So, if the artwork comes from the heart, then it will hopefully reach many hearts.”