The Egyptian-Palestinian painter embraces Old Master techniques and infuses them with contemporary influences to produce vibrant maximalist tableaux that reveal as much about the viewer as the artist.

Canvas: You received your degree from Central Saint Martins in London, but how did it all begin?

Samo Shalaby: To be honest, I don’t even remember the first memory because it’s something that I’ve always been doing. My mom and aunt are both artists. My sister has her own homeware and interiors brand, which is reflective of her very tasteful and creative approach. My father, who is in the business world, has a way of innovating that is also always very creative. I spent most of my childhood in my mom’s studio in Cairo, and as she is a bespoke artist, I was always observing and absorbing all these methods of making. My aunt had a more instinctive way of creating – figurative, spiritual and gestural. So when growing up, I was around creative people and minds, for which I’m very grateful. It started the whole ball rolling from a young age. I haven’t really stopped since. Reflecting back, having that foundation led to me finding somewhere in-between all these contrasts and taught me many of the techniques I use now.

So artistry is in your blood. Egypt and Palestine also have long histories of art making. Did that come into play as well?

It does, 100 per cent. Having a strong point of view and a voice comes from the Palestinian side, as does having the audacity to combine things that don’t traditionally go together. The idea of kitsch comes from growing up in Cairo, where colours and objects you feel would never work together within the same context somehow do. That eclectic mix has fuelled and shaped my style. I have been able to carve my own path from a great foundation.

Your style is bold, and given that your family provided a strong creative support system, have you ever faced a moment of artistic hesitation?

All artists have their blocks here and there, it’s part of the process. I have never really been turned off by anything, because for me there is no ‘too much’. I’m all about maximalism. If anything, minimalism did scare me in my formative years, which is something that I’m exploring more recently. Something that really clicked with me as a kid was seeing Hieronymus Bosch’s The Garden of Earthly Delights. I love this kind of Where’s Waldo? style of six million things happening within one frame. It’s like a TV that doesn’t move. So, minimalism took me longer to understand and connect with, but now that I have more context and understanding of things such as colour theory and energetic work, I can appreciate works which aren’t completely ‘my style’.

How do you approach maximalist compositions and deeply layered narratives without becoming overwhelmed?

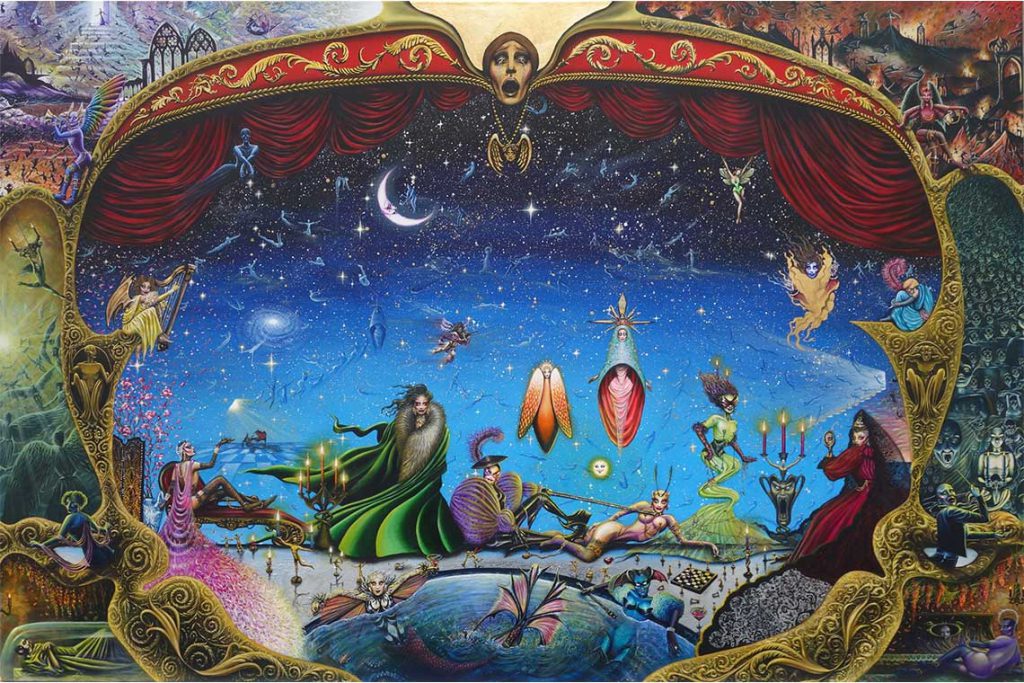

Honestly, my brain is confusing and it is overwhelming. It’s hard, but it is part of the process. To make something like that and not be overwhelmed is unrealistic, but I’ve embraced it. The Masquerade (2021–23), for example, is the third part of an eventual ten-part series that I call my “lifelong dream” because I don’t think I’ll have time to finish it anytime soon. However, I do have around 70 per cent of the pieces fully planned and sketched out with compositions, characters, colours and concepts. These stage paintings fuel my heart and soul. It’s everything that I love within one context. It takes a lot of time to make them, for example, The Masquerade took me two years on and off. I change my mind during the process about some things, but the core skeleton, composition and soul of the work always remain true.

In a way, it always happens like that because you’re creating a movie, setting the stage and filling it with characters, each of whom are placed specifically, with costumes alluding to certain factors, histories, who they may be or what they need. I’m directing a tableau vivant, and all these elements I love – film, theatre, costume, design, jewellery – come into play alongside narratives and storytelling.

Samo Shalaby. Figurative Theatre. 2021. Acrylic and gold leaf on canvas, mounted in custom wood / gold leaf frame. Framed: 160 x 200 cm (Unframed: 101.6 x 152.4 cm). Image courtesy of the artist

What was the initial impetus behind the stage series?

It started during Covid, after not having painted for two years. I felt very lost, as though painting wasn’t for me anymore. This was because towards the end of high school I was doing a lot of private commissions – which I was very grateful for – but my heart and soul were not in it, and that tainted my relationship with painting. So I went in the completely opposite direction, exploring fashion, photography, makeup and styling and having more hands-on, physical experiences. When I was alone in my apartment for eight months during the pandemic, I made the first stage painting, Figurative Theatre, which is about locks and keys. It took a whole year of daily painting to complete. The second one, Fantôme Fête, about the realm between life and death, took two weeks as I was on a deadline and, strangely, in a really intense flow where time didn’t exist. The Masquerade, a dramatic and ethereal piece about masks inspired by the films Eyes Wide Shut and Moulin Rouge, was a long time coming. I can easily fill two or three sketchbooks with compositions and all the details, making notes of who’s who, why they are standing somewhere, what they are like. I never throw sketchbooks away because I always find something from years ago that I can reinvent.

Do the elements within each stage painting exist in a single created universe that you pick and choose from, or are the works independent of each other?

The collage of ideas in my mind composes a story. Every one of the stage paintings is different but they exist within one universe. All play with dichotomies. Think of them as different dimensions of this world that I am creating. The ten paintings will all go in one room, which is why I’m refusing to sell any at this point. Combined, they will tell one big story, an ode to Mucha’s The Slav Epic and his journey of creating it.

You incorporate numerous references, but where is the line between homage and copying?

If I’m really obsessed with certain artists, or a style, or a feeling that I get from movies, for example, I try to mimic the essence rather than copy pasting. So, take Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut, which is quite sinister. I didn’t want to carry that energy into The Masquerade. There are dark elements, but not with the same connotations. Instead, I imbued the theatricality, that Venetian feeling. Sometimes it isn’t even intentional – I love Bosch because so much is going on, and Lawrence Alma-Tadema for his romanticisation of history and combination of contemporary with antiquity – and I’ll be working and think “Oh, this is quite like…”.

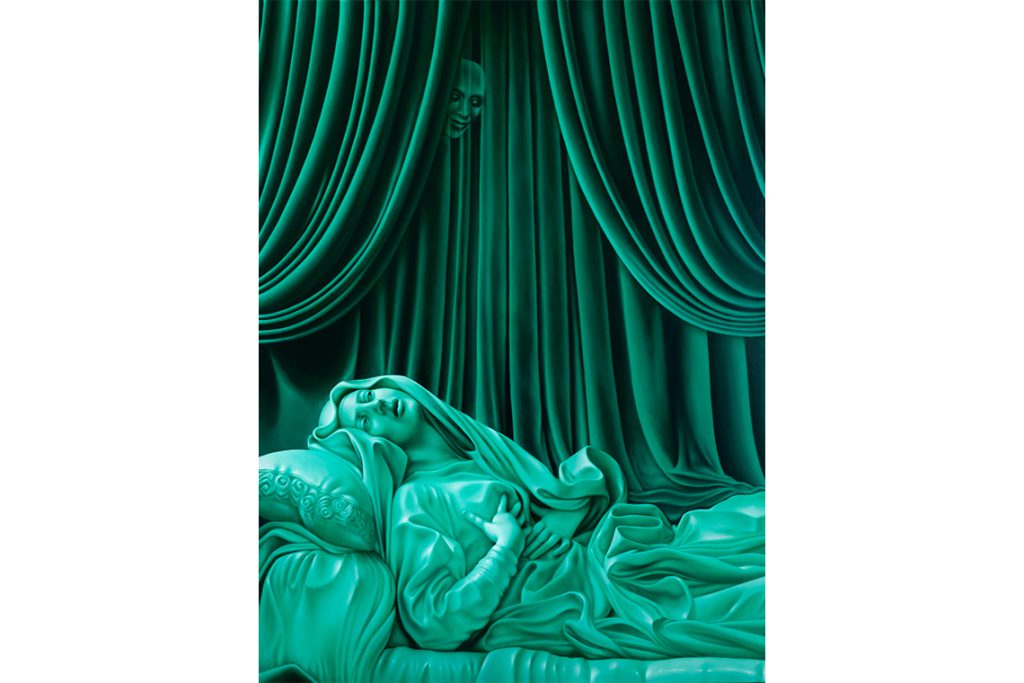

Your Curtain Call series is simpler visually, framed more tightly and merging classical with modern elements, but it still involves traditional Old Master techniques. Do you think people still learn, or care to learn, how to paint in this way?

Sometimes I think, “Why am I sitting here painting for 18-hour days?” But I enjoy it. I love the effect, the technique. I learned on my own and I still have so much to learn. I just went to the Venice Biennale and seeing all the varied art is interesting, but to be a ‘good’ painter in the contemporary art world is not what it was hundreds of years ago. Someone who paints abstractly might be a much better painter than me, even without Realism, Surrealism and colour theory, but it’s subjective. Time, labour and technique are not as appreciated, they’re seen as quite academic now, and can even appear boring to some. Painting now is more ‘do what you want’, which is great because it liberates artists from the ‘jail cell’ of painting in the traditional way. Styles have expanded. I sometimes wish I could paint loosely, but I just don’t have it in me at this stage. I’ll just be sitting here with a single-haired brush all day, and I love it. A part of me wants to break away from that eventually, but all in due course.

Is the emotive quality of a work affected by its painterliness?

I can look at an abstract painting and feel so many things, but won’t know how to pinpoint why. There is power in brushstrokes and colour. I believe paintings carry energy, especially in real life rather than on a screen. Right now I’m working on a new series where I am somewhat playing with that approach, still staying in the realm of the Curtain Call style, which is more clean cut and smooth, but experimenting with textures and grit. It’s new for me. I’m having fun scraping paint on, moving my body, broadening my horizons and deepening my understanding of gestural painting.

Colour plays a significant role in the tone of your paintings, offering a starting point for the discreet symbols within. The 7000th Floor (2023), for example, hints at something eerie or voyeuristic.

Yes. It’s very important in my work. I love suggestivism and when Old Masters plug in all these little things that are not apparent at first glance. In the stage paintings, which are so busy, they’re harder to catch, but in the simpler curtain paintings, it’s about the energy of the scene, somewhere between comfort and discomfort. Everything is composed and staged for the viewer – think of it as a performance in 2D. The 7000th Floor references the seven levels of heaven, Helmut Newton, Gary Numan’s song Metal about a robot who wants to be human, as well as Marie Antoinette’s soirées, which were very naughty. I wanted it to be elegant, but also produce that feeling of ‘I’m not supposed to be here’, inviting viewers into the in-between of public and private realms.

Is there a world where you omit colour?

Now that the Curtain Call series is complete, I’m going in a new direction that I’m calling Portals. I’m working on using colour in a different way. I’m painting in a grisaille technique, cracking the paintings with an oil-versus-water technique, then will fill the cracks with dyes, inks and pigment stains. I’m exploring a more scientific approach by playing with chemical reactions rather than staying in my comfort zone. It scares me a little, because I love using colour as a starting point and as a symbol, but I’m enjoying this new experimentation. These paintings will be eerier, more atmospheric and poetic – I’m trying to make it look like someone has a broken camera and is peering into another dimension.

Which painting has been the most impactful?

Figurative Theatre. It was a rebirth for me. That’s when I found my voice and it helped me trust my intuition. Before that I could say I was ‘technically’ okay at painting traditionally, but my heart and skills were not yet in sync. During Covid I thought that it was time to face the music. I was going through a dark period. Many people don’t believe this, but I swear this is what happened: I got a vision and started sketching it, but I felt like it wasn’t me, it was something just guiding my hand and I drew this stage exactly as it looks as a finished piece, and then I passed out with the sketchbook in my lap! Then I just went for it on this big canvas that was the size of my wall, like a TV I would look at every day. I did hundreds of layers, starting with burned goldleaf as a base. I was so consumed by it, living, breathing and sleeping the painting. It made me realise that this is the path I want to go down.

In retrospect, Figurative Theatre is more childlike and illustrative than my more recent work, but it’s a time capsule of who I was during that period. I can look at each part of it and know what I was doing, how I was feeling, and who I spoke to that day. It’s horrible to say, but in a way I miss Covid because it gave me the gift of time to focus with no distractions! I was in it 24/7. It was magical. Some people are depressed being alone, and that’s understandable, but I’m good because I have all these characters to keep me company.