Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Museum of Art has hosted the Carnegie International exhibition of contemporary art since 1896 and this year presents Is it morning for you yet?, featuring a host of artists from the Middle East.

Unlike the Gregorian calendar used in most Western parts of the world, the Mayan calendar counts between 13 and 18 months per year, depending on which of the complex parallel dating systems is used. Entitled Is it morning for you yet? after an indigenous Mayan morning greeting that acknowledges these different perceptions of temporality, this year’s Carnegie International, the oldest exhibition of international contemporary art in North America, sets out to make the asynchronisms in art visible.

Centering around ideas of solidarity, collectivity and resistance by re-examining the post-1945 geopolitical footprint of the United States, curator Sohrab Mohebbi and his international curatorial council invited over 100 artists, archives and collectives from across the world, jumping geographies, time zones and generational notions of the “contemporary.” The 58th edition of International unites historical works from collections worldwide with an astounding number of new commissions in the historical and new galleries of the landmark Pittsburgh museum.

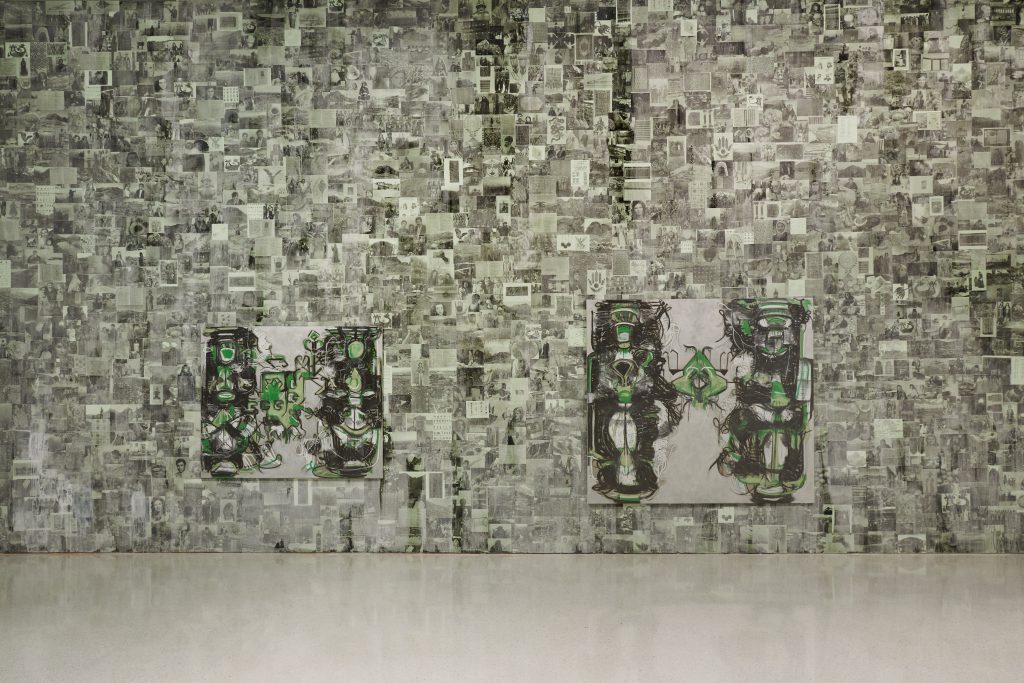

One of the first halls opens to a timely sight of US-led military violence: Ruins of Two Cities: Mosul and Aleppo (2020) by Dia al-Azzawi is a sprawling miniature labyrinth made of resin that traces the destroyed streets and alleyways of formerly thriving historical cities in Iraq and Syria. The sculptural mapping of dilapidation, described by al-Azzawi as “the ugliness of what man does to his fellow man”, is complemented by an intricate wall installation by Melike Kara that explores the histories of displaced Kurdish families through photographic materials. In her three-part work qarajorlu / pahlevanlu, darreh gaz and weaving (all 2022), the artist pastes her collected photographs onto the wall and then paints them with bleach, simulating a process of fading cultural memory that, at the same time, ties its uprooted people together.

The visual imprint of violence through photographic memory reverberates elsewhere in the show. Next to the glossy yet incisive sculpture of Banu Cennetoğlu – where bouquets of golden balloon letters spell out articles of the Human Rights Declaration and, pointedly, deflate over the course of the show – Hiromi Tsuchida’s hauntingly simple black-and-white photographs Hiroshima Collection (1982–95) take stock of the abandoned belongings of Hiroshima bombing victims in 1945, along with a shockingly sober paragraph on the deceased owners. Nearby, Mohammed Sami’s paintings vibrantly recall traumatic images of war. A close-up view of boarded-up, curtained windows in Sami’s 23 Years of Night (2022) speaks to personal disquieting memories of the Iraqi-born artist, whereas The Fountain I (2021), depicting a body of water going up in flames as bombs hit, reminds viewers of dramatic, mediated pictures of armed conflict – a curated vision of warfare that becomes painfully poignant, standing within the immaculate, classical Greek-style architecture of the Carnegie.

Other parts of the International defy chronologies to highlight collective narratives of resistance that sprouted in regions of US interventionist conflicts. Works from the Museo de la Solidaridad Salvador Allende Collection – a grassroots institution tied to socialist Salvador Allende’s short-lived democratic administration in 1970s Chile – collide with Indonesian collective Hyphen’s presentation of revolutionary female painter Kustiyah (1935–2012); The Laal Collection showcases eclectic paintings and candid polaroid party shots from artist and curator Fereydoun Ave – insights into intimate friendships that informed the politics of independent art organising in Iran of the last 50 years; Dogma collection’s North Vietnamese propaganda posters expose, quite literally, the flip side of state ideology, where, on the back of slogan-laden posters, art students practiced delicate, inadvertently daring pencil drawings due to paper scarcity in the Vietnam War.

Given the International’s convincing historical blueprint, confounding contemporary outliers don’t go unnoticed. Current art world darlings Mire Lee and Tishan Hsu, for instance – both exhibited at this year’s Venice Biennale – present intriguing, yet ill-fitted, sculptural works, including one of Lee’s signature machine that twists pseudo-organic matter around metal beams, and Hsu’s bulbous steel-and-fibreglass sculptures that greet visitors outside the museum with scannable codes printed on its surfaces. terra0’s curious crossover between forestry and cryptocurrency, A tree; a corporation; a person (2022-ongoing), is another exterior oddity – the German collective planted a tree near the museum that effectively owns its land through an NFT-based smart contract.

Melike Kara. Left: qarajorlu / pahlevanlu. Right: darreh gaz (dorunger valley / bajgiran region). Background: weaving. All works 2022. Installation view.

Photography by Sean Eaton. Image courtesy of the artist and Carnegie Museum of Art

The erratic dance across times and spaces in some parts at Carnegie is occasionally slowed by encounters with material rootedness in others. Organic matter – such as in Krista Belle Stewart’s abstract mural Eye Eye (2017–ongoing) in hues of brown ceramic pigment, or in Daniel Lie’s suspended fabrics Grieving Secret Society (2022), dyed and decomposed in turmeric – acts as a catalyst to think of global, contemporaneous art practices and cosmovisions that eclipse existent binaries of human history-telling. Ruminations on such earthen chronicles ultimately converge in the installation Tomb of King Hiram (2022) by Dala Nasser, in which the artist builds a copy of the ancient limestone tomb at Tyre with fabrics stained by local shrubbery. Its original being a century-old witness to biblical events and modern politics alike, Nasser’s textile duplicate in turn documents recent environmental and human casualties of the crisis-ridden region, inscribed in the very materials its land produces.

The inherent shortcomings of an exhibition reckoning with brutal US interventionist politics from within an American institution are only made visible in Pio Abad’s Distant Possessions (2022). The wall vinyl cannily borrows the phrase “Americans cannot be grown there” from an article on the Philippines authored by the museum namesake, Andrew Carnegie – a sign that even Carnegie cannot outrun its imperialist legacy. Nevertheless, Mohebbi’s Is it morning for you yet? manages to assemble remarkably subversive narratives of complicity, disobedience and cultural resilience inextricably entangled with overlooked histories of the 20th century. In its titular fashion, rather than rewinding the clock to present a clear-cut alternate art history reading to its visitors, the International proposes instead to upend its canonized timeline, in the hopes that audiences step out of the exhibition with a head full of unruly visions and the certainty: morning will come soon.

Is it morning for you yet? runs until 2 April 2023