In Kun: To Be, her solo show at Maraya Art Centre, Lamya Gargash toys with the generative potential she observes in liminal spaces as she moves between places and subjects.

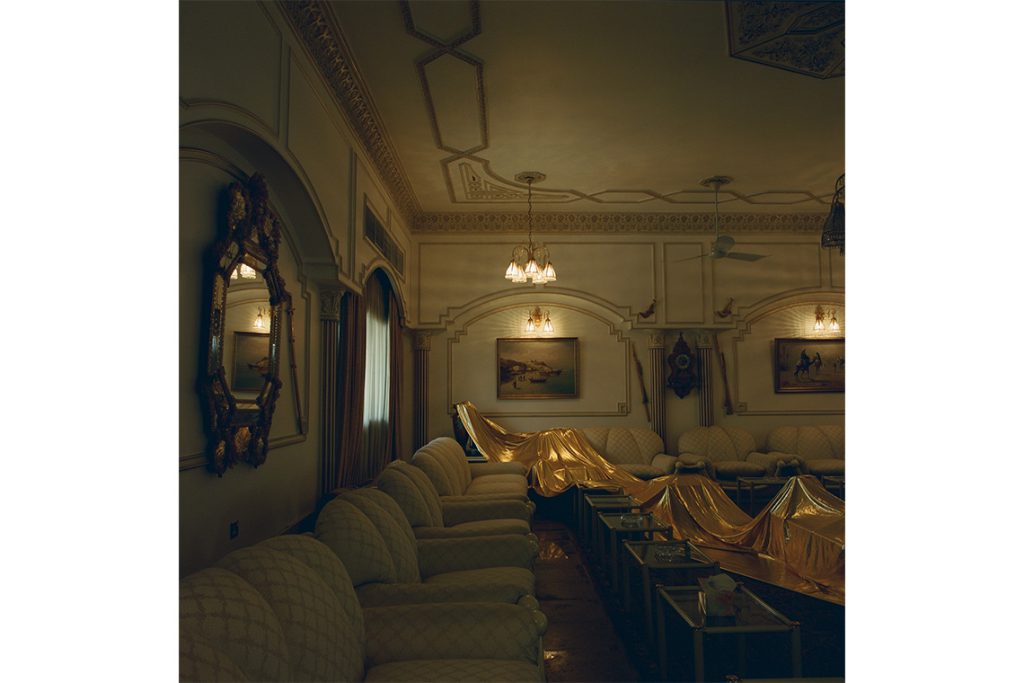

A swathe of gold fabric irrupts through static space, the unifying thread that connects Lamya Gargash’s solo exhibition at Maraya Art Centre, Kun: To Be. In this photographic series of more than 50 works, the Emirati photographer narrates her hybrid existence between the UK and UAE. Her journeys between Sharjah, Dubai, Bath and London suggest a suspended existence, but through her interventions, Gargash mends the fractures of space and time. She drapes lengths of luminous fabric through familiar but evocative territories, including the Natural History Museum in London, Zaki Nusseibeh’s book-lined corridor, her family’s majlis in Dubai and Bath’s Council Chamber. Her cloth connects distinct worlds while also acting as a compass, visually orienting the viewer toward the qibla, the direction of prayer in Islam.

Initially, the locations on which Gargash has chosen to focus her lens appear disconnected. What, after all, links a Georgian tea room in Bath to a civil engineering office in the Gulf? Yet these sites – spaces of community, governance and tradition – are where human connections and shared rituals materialise. Her chosen settings, among them the 1970s Flying Saucer, beloved by inhabitants of Sharjah, and the “Blue Whale Hall” at London’s Natural History Museum, are places that embody the architecture of collective memory.

In Knowledge Terrace, House of Wisdom, 2024, the rhythmic order of the library’s bookshelves reflects the satisfying symmetry of its modernist façade, but the work also speaks of invisible structures – the ones that constrain the way we learn. The empty stage in The Little Theatre, Bath, 2024, lit by the neon glow of a fire exit sign and a stage light cast upon a red velvet curtain, reminds us that our cultural performances also dictate to the spaces they animate. Such domains express an unspoken divinity – not in a strictly religious sense, but in their ability to preserve, gather, and reflect human experience.

Beyond her personal engagement with these environments, Gargash reveals a shared visual language that unifies her chosen settings, articulated through the rhythms of their spatial order. Recurring motifs – chandeliers, carved wood and swirling moulding on ceilings – introduce a sense of continuity through disparate spaces. In Room 18, Regency, Romantics and Reform, portraits of Regency-era aristocrats line the terracotta walls of London’s National Portrait Gallery, while in My Grandfather’s Majlis View 2, faint depictions of camel trails and dhows evoke Gulf traditions and the legacies of previous generations.

In placing these seemingly unrelated trajectories in dialogue, Gargash considers transcultural practices of documentation and cultural transmission – such as portraiture – as a means of capturing moments from the past and allowing them to speak anew in the present. Her work invites the viewer to engage in the humbling task of locating themselves within the continuum of history, suggesting the universality of shared human practices that transcend time and place.

In parallel, she embraces the aesthetics of dislocation; her spaces are intentionally framed without human figures yet feel alive with cinematic tension. It is work that recalls that of German photographer Candida Höfer. Like Höfer, Gargash uses only available light – natural, artificial or a layering of the two – mounting suspension in her scenes through tension between light and shadow. Dimmed chandeliers at dusk, sheer fabric guarding against desert sunlight, and corridors touched by fading daylight invest her shots with an eerie stillness. There is a sense that the former inhabitants have only just moved out of frame. Gargash sees empty theatres, libraries and concert halls as liminal spaces – thresholds where transformation might occur.

Image courtesy of the artist and The Third Line

Such desolate interiors evoke Mark Fisher’s notion of the “failure of presence”, where absence reveals the intended purpose of a place yet renders it hauntingly unresolved. Gargash’s gold fabric manages to reanimate these domains, countering their desolation with kinetic energy. It snakes through rooms, echoing the curves of their architecture. Its folds suggest extra depths, leading the viewer to imagine what remains unseen. Gargash’s play between concealment and revelation speaks to broader tensions: between secular and spiritual, permanence and transience.

Kun: To Be – a phrase that, in both Arabic and English, signifies an active state of existence – imagines spirituality as unbound, extending past traditional spaces of worship. Gargash’s series suggests that transcendence might also be possible in settings where music, art, conversation and ritual unfold, connecting the sacred with everyday human practices. Her gold cloth, oriented toward the qibla, evokes the symbolism of a prayer mat; her intervention with this fabric operates as both a unifier and a disruptor. In weaving it through liminal spaces, she reclaims them as active sites of spiritual engagement accessible to all. The cloth not only reflects movement through physical realms but also captures the lingering presence of those who came before, suggesting a continuum rather than a rupture.

Through Kun: To Be, Gargash explores how the spaces we inhabit inform our actions and how we, in turn, imprint ourselves upon them. Her lens captures, with precision, not just the physical but also the intangible – the atmospheres and emotions that transform static space into a site of meaning. In so doing, she frames the act of being as one of connection.