Amidst the early incomprehension of the Covid-19 pandemic, an informal collection of artists responded to their shared sense of loss and trauma through the production of individual artist books. The full results of the project are now exhibited for the first time altogether at Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art in Doha, combining into a sensational archive of a universally challenging time.

There is sometimes nothing more anxiety-inducing than an empty page. As many artists will attest, staring at a blank canvas can be overwhelmingly daunting. Blank pages, however, are exactly what 58 artists unexpectedly received in the post over the summer of 2020, when entire populations were trapped at home at the start of the Covid-19 pandemic due to global lockdowns and most were craving the communities from which they had been suddenly cut off.

Artist Ghada Khunji was isolating in her native Bahrain and likens her seclusion to that of Jack Nicholson’s character in Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining (1980): a state verging on insanity. “Very quickly I became depressed,” she recalls. “I could not bring myself to make any sort of art, and doubted I would ever come up with ideas again. Then, out of the blue, I got the blessing that I so needed. Dongola Limited Editions invited me to be a part of a very special initiative, Cities Under Quarantine: The Mailbox Project. I was sent a handmade book from Lebanon and asked to produce a unique art book relating to our time in quarantine. Somehow it felt sacred.”

Thankfully, the Lebanese artist, curator and co-founder of publishing house Dongola Limited Editions, Abed Al Kadiri, had been more productive than most during that disorientating time. The shock of the pandemic had catalysed an idea that he had been formulating for a while, involving the production of his own artist book, but his discovery of the John Baldessari quotation, “It is difficult to put a painting in the mailbox”, sparked a final flash of inspiration. Al Kadiri reached out first to a courier company, then to his extensive network of artist friends and sent them each a blank, hand-made and personalised artist book, for their use in whatever way they saw fit. “I put it to them that this is a project about friendship, and this book is not an obligation,” he explains. “This isn’t some institutional commission. It is a gift. Not one of them refused it.”

The resulting artist books of The Mailbox Project are as diverse and insightful as you might imagine, and all are currently exhibited together for the first time at Mathaf. They range from the bright and broad brushstrokes that fill Samia Halaby’s The Dongola Book (2020–21) to the macabre tar-blackened pages of Hani Zurob’s Zeft Book (2020). For some such as Zurob the hardships of the pandemic were relative. “I was not vexed by the pandemic lockdowns,” he writes in his accompanying statement, something that Al Kadiri asked of all the artists as a further document of their work. “The isolation state mirrored the reality that I had lived before, still live in, just like the desolation, segregation and confinement that Palestinians face daily.”

It is mercifully clear that Cities Under Quarantine is not a show about the pandemic, full of whimsical drawings of gardens as seen from a bedroom window or other clichés about life indoors. This is a show born from the equalising horror of the pandemic and the existential questions that it triggered worldwide. It’s about life and death, and what both sides of that binary look like when the barrier between them becomes so fragile you can almost see through it. At a time of ubiquitous vulnerability, Al Kadiri sent 58 of his most trusted friends a collection of blank pages, and asked for nothing more in response than what any were willing to give. Terrifying for some; a lifeline for others. The faith Al Kadiri put in his friends, repaid in full, makes The Mailbox Project a singularly complex archive, completely in and of its time.

“We were suffering a collective trauma,” continues Al Kadiri, “confronted by all these images of death. Most of the artists were really struggling to keep a peaceful momentum, so I think they all translated these states of discomfort through their books. That’s what makes this a really interesting historical project for me. I will like to see how it is studied 30 years from now.”

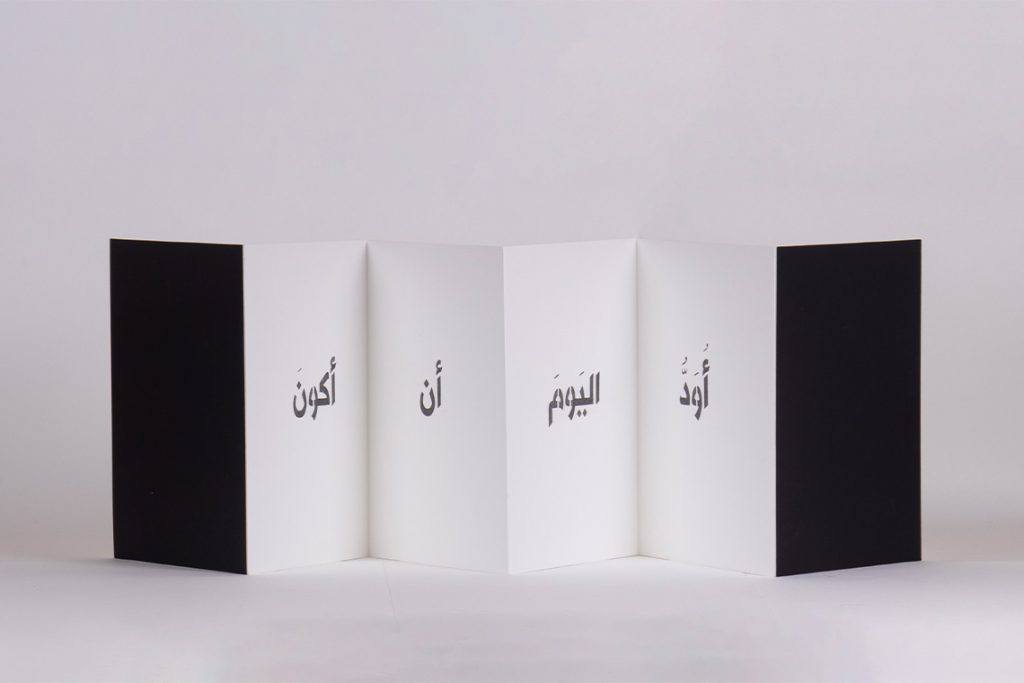

The project was doubly powerful for Al Kadiri whose life and book were interrupted by the explosion in Beirut in August that year, which “took with it every shred of meaning”. The reverse of his book is left white in an unspoken tribute to this shattering experience. “When the explosion happened, I was in the middle of creating my book, brainstorming about a project called ‘Today I Would Like to be a Tree’. After the blast I left Beirut and I left the book. I only came back to it a year later when I wanted to exhibit the books in Villa Romana in Florence. That’s why my book in the exhibition today only has ‘Today I Would Like’ on one side, and the other side is left blank.”

The far-reach of the blast is felt in the books of other Lebanese artists, even those who quarantined in distant cities. The pages of Amsterdam-based artist Mounira Al Sohl’s book In Zigzag In Blood On Carpet (2020–21) are stained with her own blood, and, almost as if unknowingly trying to soothe the pain of Al Sohl’s response, Dalia Baassiri’s Sink-ronized (2020–21) shows high-resolution pencil drawings of bubbles, soap-suds and other acts of cleansing, optimistically questioning “Is cleaning Beirut possible?”

Death, unfortunately, maintains a constant presence throughout the show, which opens with a poignant tribute to the Palestinian artist Laila Shawa. The white pages of her untouched book, which she was never able to work on due to illness, is positioned by the entrance, alongside one of her pieces from Mathaf’s collection – the only artwork in the show that is not a book.

Other exhibited artists to have passed away since the beginning of the project include Mona Saudi and her daughter Dia Batal, whose Death by Celestial Bodies (2020–21) – featuring drawings of cancer cells with gold leaf as “a conversation with death” – is particularly moving. Yet as it was possible to include both their completed books in the show, Al Kadiri felt the opening tribute dedicated to Shawa would be special, deeply symbolic in the sense that artists are not justified by the final outcome of their works. “We lost three great female artists on this project. Their losses were all very painful news to me. Laila Shawa was one of those great artists whom I was always proud to have a close friendship with. I remember she would always take the opportunity to have dinner with me if I was in London. It is something great about that generation, their ability to empower friendship.”

The future of the project will once again rely on principles of friendship and solidarity in the face of existential danger, as another Mailbox Project has been set in motion. The same participating artists will soon be receiving a second book, personalised and blank as before, this time requested by Al Kadiri to respond to the continued war in Gaza and the unconscionable civilian casualties at the hands of Israel, and the systematic erasure of Palestinian identities. “Today we are still going through catastrophic events in the Arab world, and I’m sure this project will be another powerful piece of documentation. Not only for the Middle East but the world in general.”

As the artists once again prepare to receive an empty book sent to them by Al Kadiri and confront the limitless potential of its blank pages, who can say what these generational voices will produce next?

Cities Under Quarantine: The Mailbox Project runs until 4 May 2024