The group exhibition Neither Here ~ Nor Elsewhere, curated by Sanaz Askari, mines its energy from the potential unearthed in the periphery.

Marginal spaces are frequently framed in terms of oppression and limitation, but can also be seen as sites of radical possibility. It is this tension that fuels Neither Here ~ Nor Elsewhere, a group exhibition at The Third Line envisioned by independent curator, Sanaz Askari. Featuring artists with roots in Africa and Asia – Faissal El-Malak, Hayv Kahraman, Mahsa Merci, Michael Ho, Omar Mismar, Sam Samiee, Sophia Al-Maria, Soufiane Ababri, Tahmineh Monzavi and Yumna Al-Arashi – the exhibition spans photography, video art and works on canvas and paper.

The selected works confront the forces that threaten to confine these artists, and through their practices, they imagine new ways of being in the world. Askari’s curatorial approach builds on the belief that art can challenge entrenched hierarchies, echoing the French philosopher Jacques Rancière’s assertion that art has the power to disrupt the established order and reconfigure how we see and understand our social worlds. This sense of disruption infiltrates the exhibition space; the works on view push back against the boundaries their creators face, whether physical, structural or conceptual. They are riddled with desire and fear, subversion and escapism.

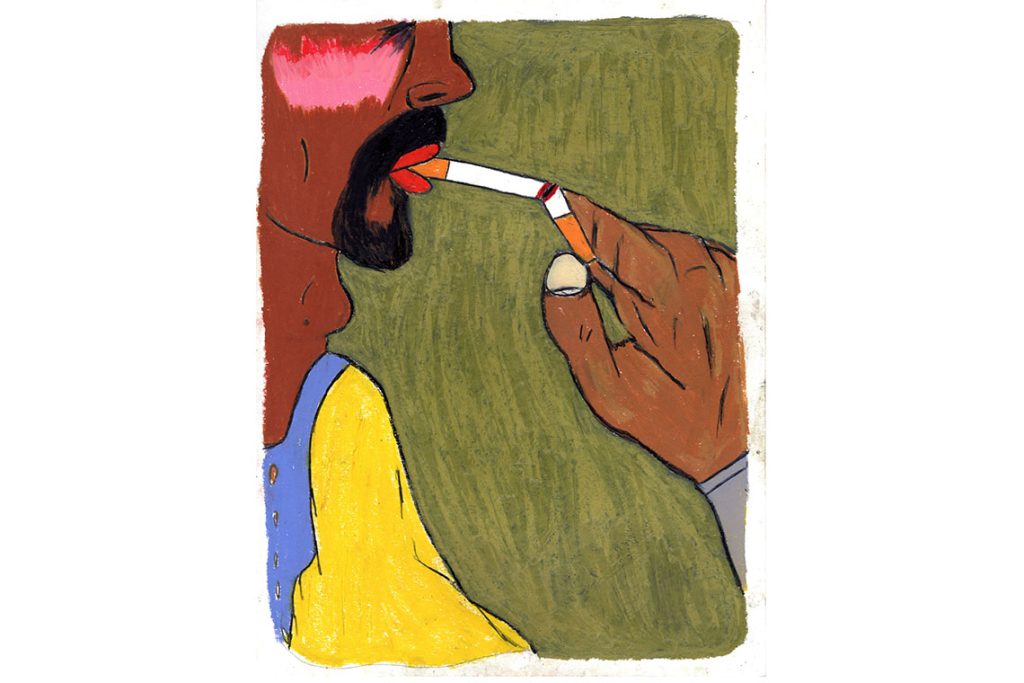

Soufiane Ababri’s Bedwork series typifies this energy. Produced between 2017 and 2022, the series is among Ababri’s most celebrated to date. Raw and bold, his coloured pencil drawings on paper, exhibited here as a cluster of 18, lure viewers with their playful simplicity. Yet his seemingly innocent scenes enclose deeper, often unsettling truths. Living between Paris and Tangier, the Moroccan artist addresses us from a vantage point that reflects the layered complexities of an Arab immigrant navigating the meeting points of a religious upbringing, diasporic identity, social stigma and a post-colonial consciousness.

Ababri’s portraits depict male figures in moments of tenderness and violence: lighting a cigarette, gazing out towards the sea or being pinned to the ground by police officers. Drawing while lying in bed, Ababri rejects the upright posture of studio practices and the traditions of the art academy, rendering a position historically associated with Orientalist passivity an act of defiance. His choice of medium is equally subversive. Coloured pencil, often dismissed as unsophisticated, is a tool for reshaping his subjects’ narratives and through which he challenges the conventions of art-making itself.

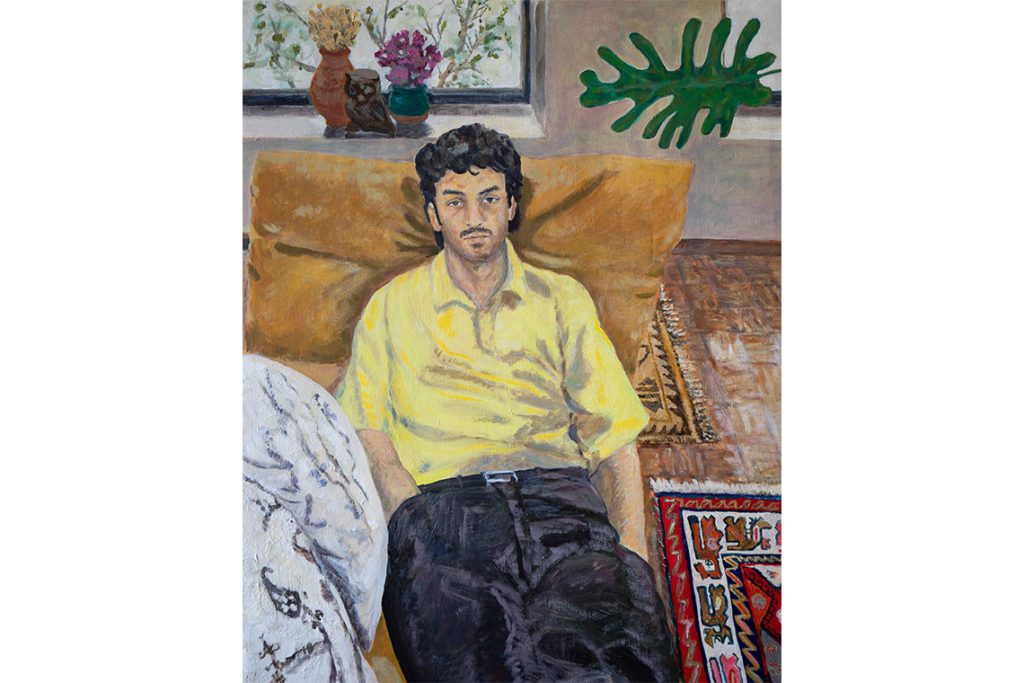

The exhibited artists deploy various strategies of creation to counter the forces that constrain them. While also concerned with the framing and agency of the male body, Sam Samiee’s three paintings embrace a distinct approach. The Iranian-Dutch painter elevates his subjects through a prolonged and deliberate process. He engages traditional painting techniques to offer up counter-narratives of the bodies seldom encountered in the Western art canon. In his series Nastaliq Might Be an Indian Boy (2024), Samiee casts young men from the nations of the Islamicate East as his protagonists, portraying them in contemplative or staged settings influenced by the aesthetics of Bonnard and Matisse. The series title references Nastaliq, a calligraphic style central to Persian and Urdu traditions; here, the term acts as both a unifying force and a marker of cultural specificity.

Samiee’s approach feels like an act of defiance, a tonic to the epistemic violence that has historically distorted representations of men from these regions. In painting his subjects slowly and with care, enriching his figures through psychoanalytically informed dialogues with his models, Samiee produces multi-layered work that contests monolithic portrayals. Elevating the crease of a shirt or the way soft daylight glazes the nude torso, his nuanced interpretations invite reflection on the stereotypes that haunt these individuals and the places and spaces that their bodies can/cannot inhabit.

For other artists, the male form manifests as an absence – a spectral presence that lingers in the margins. Omar Mismar’s neon installation, The Path of Love (2013–24), examines the fleeting intimacies of digital connections, mapping the artist’s pursuit of desire and proximity. Over a month in San Francisco, the Lebanese conceptual artist used a geolocation-based dating app to navigate the city, selecting one desired individual each day and moving as close to them as the app’s technology would allow.

The resulting installation is a luminous archive of these journeys, a glowing map of red lines that chronicle Mismar’s daily movements – his “paths of love”. It interrogates how technology reshapes the way in which human bodies interact with urban spaces, driven by psychological longings and the quest for connection. The work is also imbued with a sense of unease, as closeness is always precarious, shaped by the anonymity and exposure that define encounters in the virtual world. The Path of Love acknowledges the fragility of these encounters, capturing a struggle between liberation and constraint, where the promise of belonging hovers just out of reach.

There’s an unspoken awareness of boundaries – public and private, acceptable and deviant – palpable in Mismar’s work that resonates across other contributions. As a second-generation immigrant from China, Michael Ho turns to his art to investigate experiences and conceptualisations of the Chinese diaspora, cultural mismatch and rediscovery. His project and film Empty Orchestra (2021) offers a layered critique of the ‘model minority’ myth and the political silence often associated with Asian identities.

Framed through the lens of China’s KTV culture, Ho takes karaoke – a practice of joyful rebellion and expressive release – as his metaphor. For him, karaoke rooms, semi-secluded from external pressures, offer fertile ground for exploring selfhood, desire and collective memory. Here, the illicit and the sentimental collide, creating an anarchic space where people can come together and voice that which might otherwise remain unspoken. His performers are, however, rendered anonymous, feature-less and partially obscured under the wash of a pastel-hued filter reminiscent of the kitsch backgrounds found in karaoke machines. In concealing his subjects, he offers them a layer of protection and suggests the contingency of their safety and ability to speak.

Themes of love, longing, and care – and their shadows of pain, yearning and exclusion – permeate the exhibition. In The Limerent Object (2016), Qatari-American artist and filmmaker Sophia Al-Maria explores the tension between male and female archetypes, framing desire as both a generative and destructive force. Al-Maria frequently turns to sci-fi and fantasy as tools to process the anxieties of her lived environment, shaped by a life between the Pacific Northwest and the Gulf, and by exposure to the stark realities of climate change and environmental degradation. Here, fantasy serves as both critique and escape. Against the backdrop of an apocalyptic Holocene landscape, she tells the story of humanity’s final man, a figure consumed by an obsessive longing for an alien queen. The queen, a paradoxical figure of seduction, embodies both salvation and annihilation, reflecting the duality of desire’s power.

Image courtesy of the artist and The Third Line, Dubai

Drawing from Polynesian myths in which creation arises through destruction, as well as Palaeolithic goddesses and the Martian-like rock art of Algeria’s Tassili n’Ajjer, Al-Maria harnesses the limerent object – a figure of unattainable desire – as a potent symbol. Her composition contrasts humanity’s fleeting obsessions with the vast indifference of the cosmos, inviting reflection on what we value and how our desires might lead us to ruin.

Across Askari’s curation, the body emerges as a site where power struggles, desires and resistance might play out. Deleuze’s postmodern concept of “becoming”, that identity arises not through stasis but through transformation, feels relevant here. Fluid and unfixed, the body is harnessed as a site of emancipation and multiplicity by these artists. Iranian artist Tahmineh Monzavi’s monochromatic film OXYS (2013) imagines the bare female form as a reservoir of love and endurance, lodged within the solitude of imprisonment. Her work confronts the suppression of women, presenting survival as both a spiritual and physical act of defiance. Inspired by her own incarceration, Monzavi reflects on isolation’s corrosive effects and the innate need for human connection, creating a metaphorical pregnancy as a symbol of life and purpose, enduring through adversity.

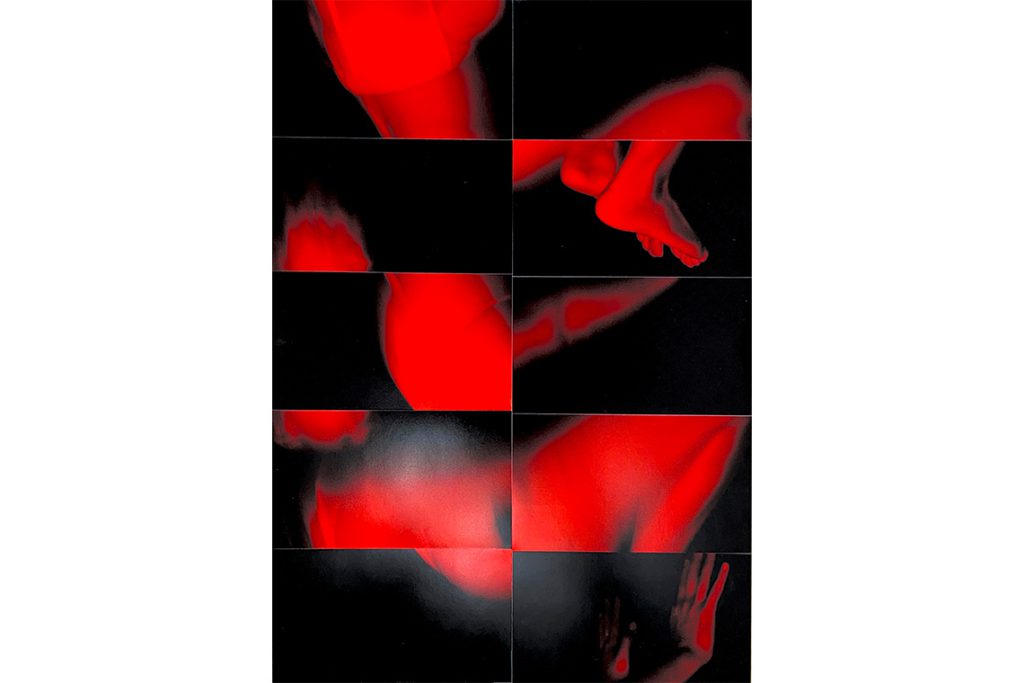

Similarly, Yemeni-Egyptian-American photographer Yumna Al-Arashi’s self-portraits reclaim the portrayal of women’s bodies. Her four digital collages, rendered in stark black-and-crimson tones, resist reductive depictions of femininity through abstraction and disfiguration. By revisiting her unpublished archive, Al-Arashi transforms self-portraiture into a subversive act by slicing, fragmenting and reconfiguring her image into intimate but unrecognisable forms. Her compositions evade the limiting frameworks that shape how women’s bodies are seen and discussed, instead asserting the complexity, autonomy and sovereignty of her identity.

What happens when the margins become a space of potential rather than exclusion? Rather than offering neat critiques, Neither Here – Nor Elsewhere unpacks the complexity of subliminal spaces – at once sites of constraint and transformation. The works occupy these thresholds, neither fully claimed nor entirely abandoned, carving out places for expression and community. In rejecting mechanisms of control and probing the fissures in societal and institutional structures, the artists propose radical acts of reclamation. The margins, they tell us, are often where change begins.