The recent edition of Asia NOW in Paris boasted some leading names but overall struggled to pass the quality test.

Paris’s Asia NOW fair, now in its ninth iteration (20–22 October), promised much to the casual visitor. It boasted a good six dozen top galleries from who knows how many countries, an interesting curatorial statement of intent, courtesy of the Eurasia-focused art collective Slavs and Tatars and, in the form of the former Paris mint, a spectacular setting ideally suited for this type of event. Why, then, did it only half-deliver on its theoretical promise?

The principal answer is that much of the work on show was, at best, mediocre. Blue-chip galleries from Europe and the Far East mostly played things safe with displays of rather forgettable paintings and shiny, often outright vulgar, sculptural installations. Too many participants seemed to be testing the water, hesitant to field anything remotely challenging.

The much-heralded stewardship of Slavs and Tatars may have held some clues. The forces that govern this inventive collective commissioned 14 artists from the Central Asia region to create a series of interventions fashioned from textiles. The first one I encountered was the most successful: what looked like traditional nomadic robes, covered in brightly coloured patterns hung from the ceiling of the Monnaie’s grand entrance stairwell, looking for all the world like the kind of makeshift decorations installed in the Kiev metro when its stations were repurposed as bomb shelters. Labelling, however, was confusing and information poorly elaborated: it was nigh-on impossible to tell which piece belonged to which contributor.

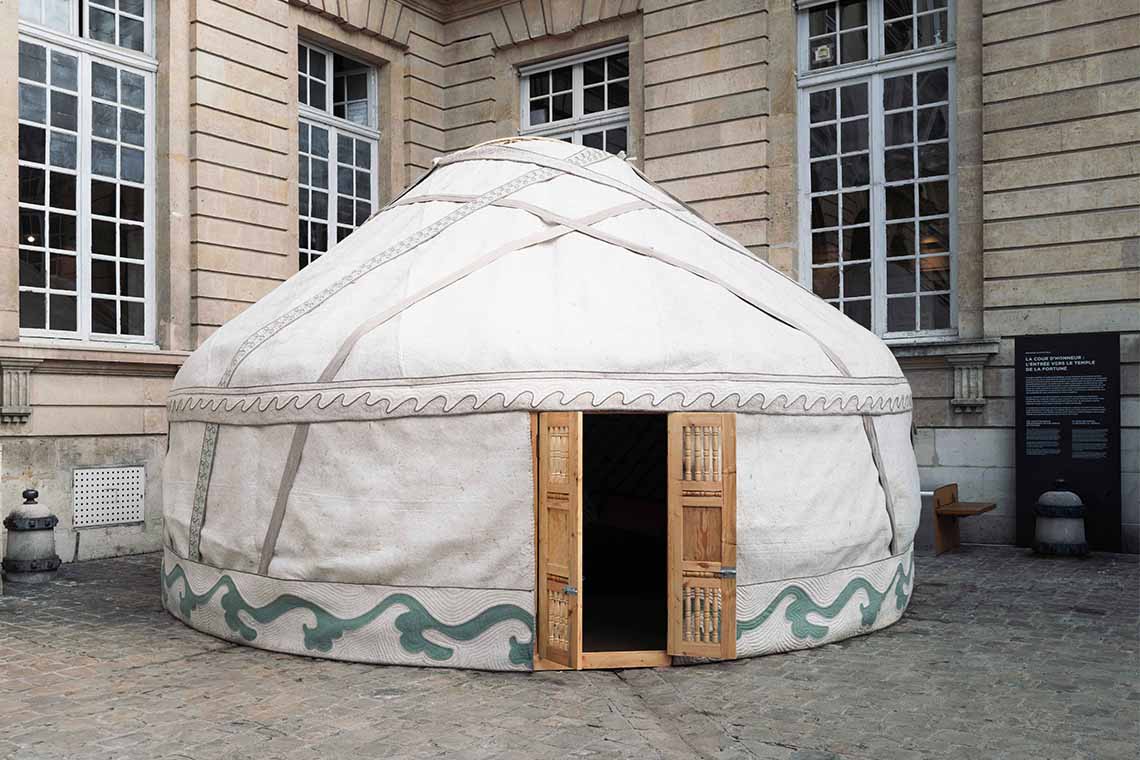

Elsewhere, in the building’s Cour d’Honneur, the collective had constructed a full-scale yurt, its interior furnished with couches and a stand serving steaming samovars of tea. The traditional nomadic structure stood directly opposite a plastic-and-steel gazebo erected specifically for the fair’s gallery displays. The effect of this juxtaposition was refreshingly jarring: I couldn’t help but wonder whether it might have been an intentional riff on the changing nature of temporary, moveable architecture and its various purposes. The yurt, embellished with elegant patterns, was as much work of art as practical building; the gazebo, emphatically, was not.

Elsewhere, however, Slavs and Tatars’ efforts were muted. Strands of fabric or more of those kaftans, spread around the premises in various locations, were barely noticeable amidst the crowds and the more attention-grabbing gallery stands. It’s perhaps unfair to find fault with the collective itself – the limitations of putting together a show at a commercial event in an historic building, itself presumably subject to any number of health, safety and security regulations, will always make pulling off a ‘guest-curator’ role difficult in the extreme. But the overall effect was decidedly anticlimactic.

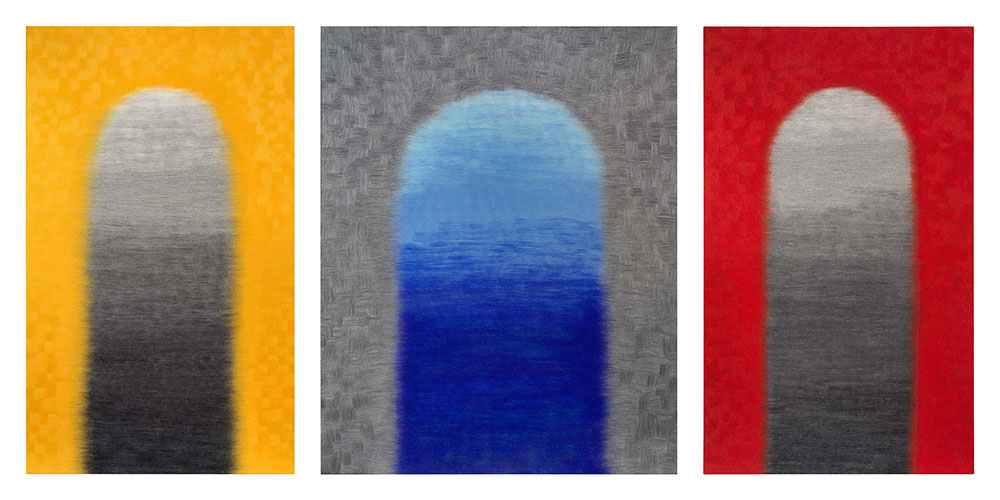

Nevertheless, the wider event was by no means a total disaster. One particularly impressive stand came courtesy of Berlin’s Galerie Michael Janssen, where Kazakhstan’s Gulnur Mukazhanova was displaying a series of canvases that in composition appeared to mimic post-ab-ex colour field paintings. Look closer, however, and their expressive, seemingly spontaneous explosions of bright yellow and shocking purple had been created from densely woven felt. At Seoul’s Gana Art, meanwhile, Park Sukwon presented a wonderful series of geometric drawings for which strands of Korean tracing paper supplanted pencil as a medium.

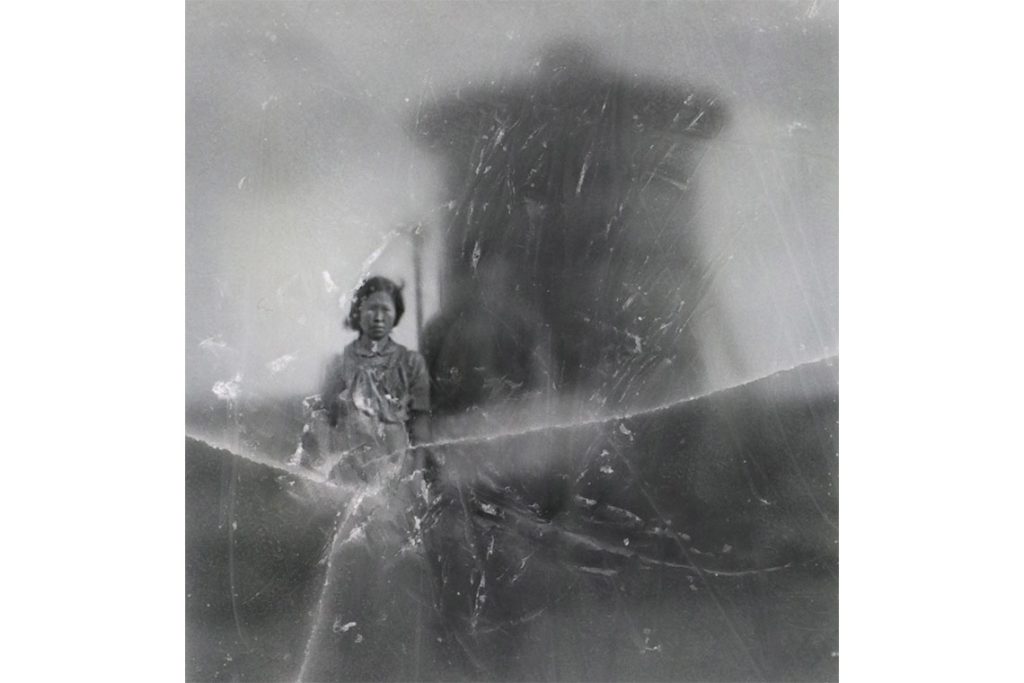

A number of ‘special projects’ were also speckled across the venue, most of which were entirely forgettable. The exception was Alexander Ugay’s presentation, courtesy of the ever-interesting Nika Project Space. In 1937, Ugay’s family were among thousands of ethnic Koreans deported from the Russian Far East to Kazakhstan by the Soviet authorities. Little trace survives of the once-widespread Korean presence in the former region, and in exile, the remnants of these communities have been able to retain little of their culture: indeed, few still speak the Korean language.

Working with AI algorithms, Ugay has created a series of images recreating invented memories of the deportations and the communities they destroyed or displaced. Using the only remaining photograph of his grandmother, he has created a series of fake documentary photos purporting to be a taxonomy of Soviet-Korean women’s facial types; a picture of his parents sitting on the steps of a gazebo served as a basis for a series of haunting photos printed onto wax, depicting an AI-generated 1930s Korean family standing around a wooden structure. Historical artefacts, Ugay reminds us, are always used to subjective ends. Often enough, any ‘meaning’ they communicate is entirely invented.

That Ugay’s project was one of a vanishingly small number of conceptual works on display made it stand out all the more. Mediocre paintings and bling-bling sculpture may be good business for galleries at present – and this is, after all, the point of the event – but at a show this big, the sheer number of them, and the lack of variety this engenders, made for a dispiriting visual experience. Participants at fairs would do well to take note.