In his debut exhibition in London, Ibrahim El Dessouki places the viewer in a barren landscape, involving them as witnesses of Egypt’s turbulent past.

Ibrahim El Dessouki began his artistic education in secret. At just eight years old, he discovered how to break into his father’s treasured collection of art books (supposedly secured in locked cabinets) and would pore over them late into the night. His favourites included those of Max Beckmann, Hans Holbein, Oskar Kokoschka and Johannes Vermeer. Since asking his parents about the more advanced details of what he was witnessing would have revealed his clandestine studies, the young autodidact was left to piece together an understanding of these new visual worlds on his own. It was the beginning of a lifetime of learning and he has since found success in both academia and fine art. Today, the Egyptian artist’s refined practice combines the rigour of both disciplines.

El Dessouki’s inaugural exhibition in London, Testimony of the Soil, curated by Sara Raza, is the product of a “two-year trans-cultural reciprocal exchange” between the pair. On display with Hafez Gallery at Frieze’s No.9 Cork Street location, it centres around four bodies of work that describe Egypt’s tumultuous modern history through the allegory of a desert landscape and its surviving vegetation.

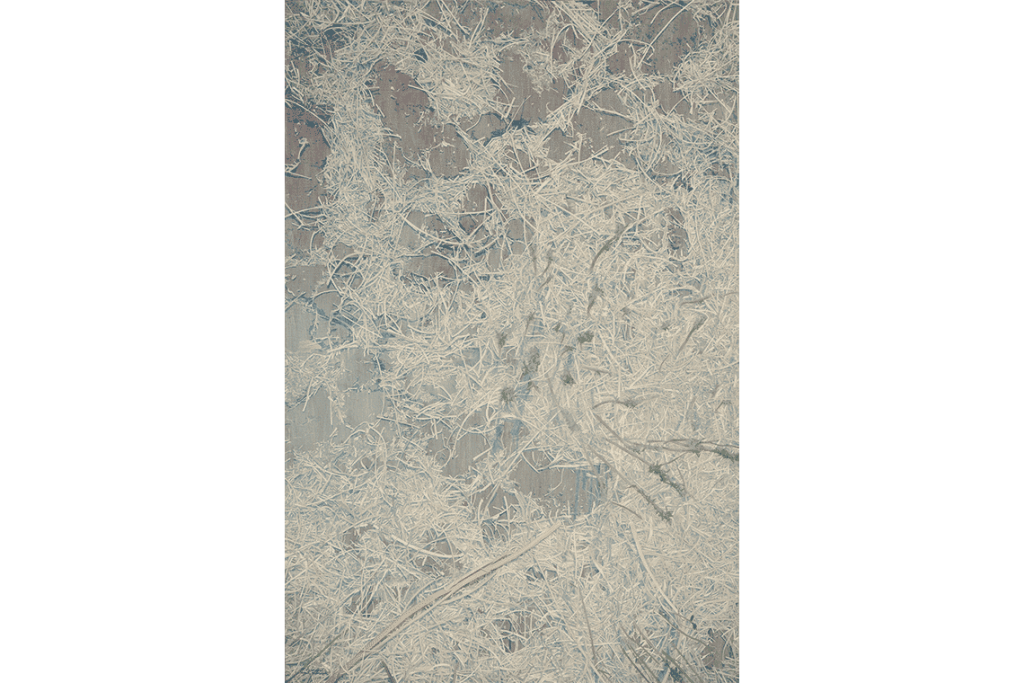

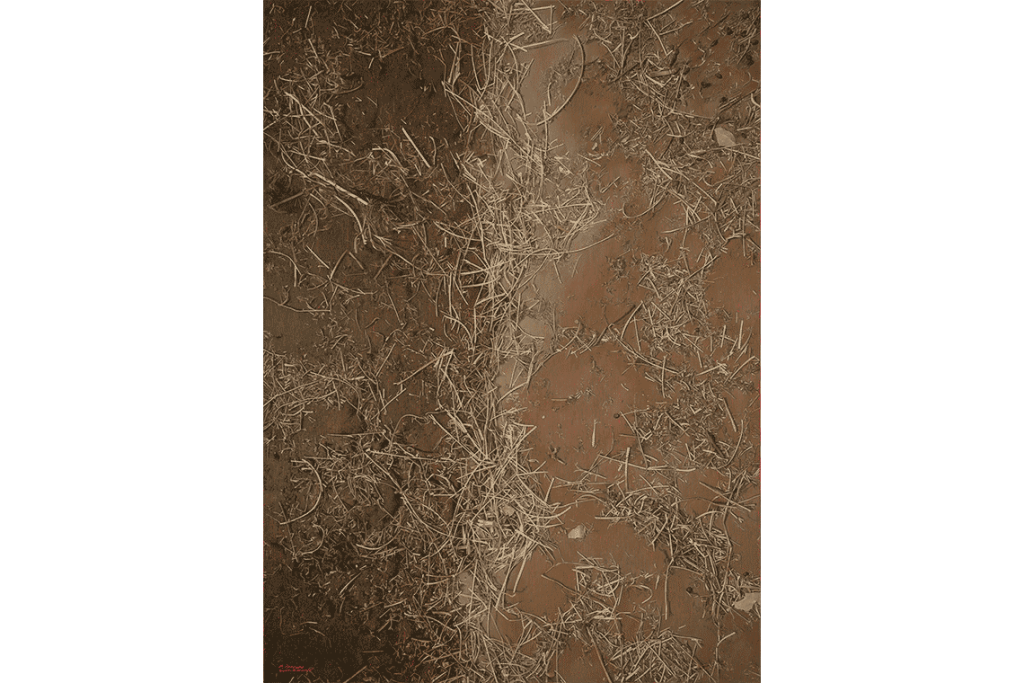

His Earth Paintings depict a barren land, with desiccated debris painted with such precision it resembles scars and slashes in the sun-baked soil. His Olive Trees hang onto nutritionless sand for dear life, whereas rather more luscious Cacti exude a casual resilience. The artist’s detailed technique is marvellous to behold, both when standing back and getting right up close to the canvas. The twin olive trees in particular are beautifully intricate; such is their level of complexity that each took almost a year to complete, with each leaf individually rendered.

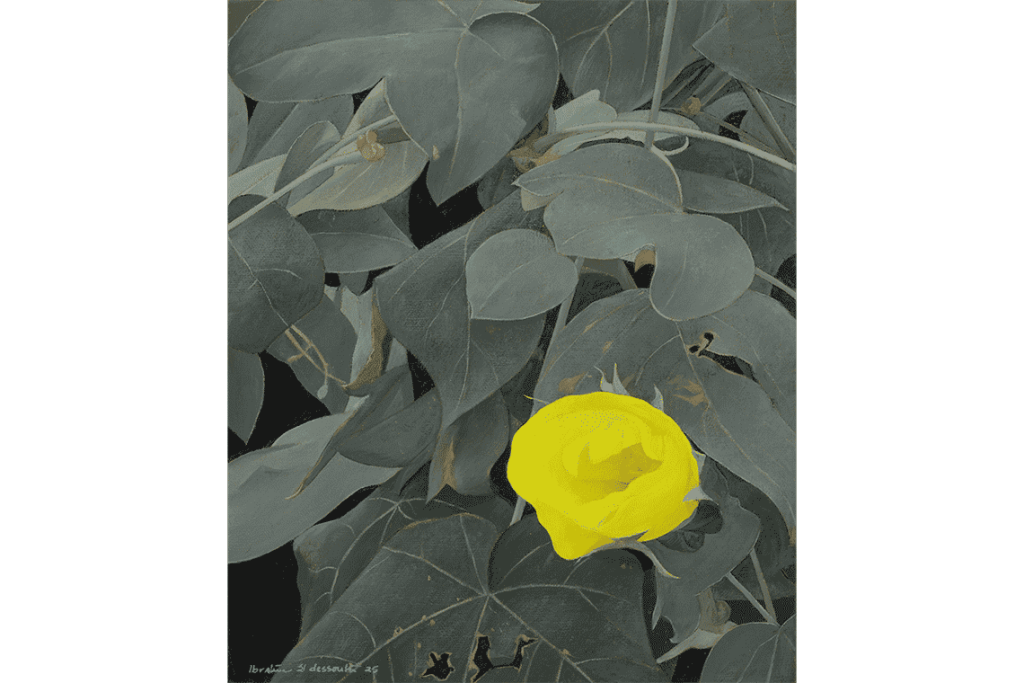

Yet El Dessouki’s high-minded approach lends the exhibition a deeper intellectual level than sheer visual impact. His latest series, The Cotton Flowers (2025), most crucially represents this dichotomy – their serene petals belie their exploitative and blood-soaked histories that have stripped Egypt’s land of its vitality. The country’s famed cotton production stretches back millennia, but under its occupation first by the Ottomans (1530s onwards) and then the British (1882–1956), it morphed into a familiar tale of exploitative practices, land seizure and profiteering. Perversely, an unanticipated result of the abolition of slavery in America was the intensification of cotton production in Egypt, due to demand for the “white gold” no longer being met elsewhere. This unsustainable pressure exploded into revolution in 1952, when the fellahin – farmers and peasants who had been ordered to grow cotton instead of crops – led to a civil uprising that overthrew both the monarchy and British colonial rule.

Famine and social collapse, the results of the abuse of both land and people, had brought the country to its knees, but that did not necessarily mean progress was inevitable. Starkly similar motivations lay behind the more recent Egyptian Revolution of 2011 (poverty, corruption, political oppression), with El Dessouki both witness and participant. “After 2011, our dream was to rebuild our country from scratch,” he recalls. “That led me to this exhibition, which demonstrates a line between life and death. It reveals the blood that was given in vain when the streets of Cairo were full of it. I have painted our dreams, our depression, our questions, our hopes. I’ve painted the history of a country wishing to live – a country that has the capability to be great, but is always prohibited from becoming so.”

El Dessouki’s works reveal that blood quite literally – using the keen edge of a razor blade he opens up slits in his Earth Paintings to reveal their blood-red underpaint. Yet, as with all his work, this subterranean effect operates on a deeper level still. He explains the specificity of the imagery through two points of inspiration. Firstly, the quotation “If the earth is thirsty, we will irrigate it with our blood”, taken from Youssef Chahine’s film Al Ard (1969) set amidst the 1930s struggle between peasants and landowners, and furthermore an image from Mikhail Sholokhov’s Nobel Prize-winning novel And Quiet Flows the Don, in which, after civil battles in 1920s Russia between the Reds and the Whites, Cossack riders galloping over fresh battlefields would churn up blood and gore from beneath long grass with their horses’ hooves.

While awareness of these two anecdotes certainly intensifies the bloody images, it would have been impressive for the casual viewer to have picked up on them without prior knowledge. Yet the artist is undeterred from layering his paintings with a lofty resonance that makes the viewer have to work to understand. He notes James Joyce’s Ulysses (1920) was “not written for readers, but for writers”, which is not to say that his paintings are as impregnable as Joyce’s prose – the imagery is still remarkable to take in at face value – but there is no doubt that they yield greater emotional responses to those willing to analyse and interrogate them.

The active participation of the viewer in Testimony of the Soil is a point made by Raza on a tour of the exhibition. She notes the paintings’ lack of figures, an unusual departure for El Dessouki, who is well known for monumental portraits of women. Here the only characters are plants; some close to death, others striving towards the sun, but all surviving witnesses to the social and economic malpractice that has driven the land to breaking point. She states that the role of the viewer is to activate the work – to become the sole human presence in the dialogue between life and land. She stresses that to be a witness, you must first be a participant; in other words, to understand the work, you must get involved in it.

The question of participation, even when the events and histories represented here may seem remote for some, also challenges the audience’s complicity. Having witnessed, we are aware. Being aware gives us agency in how to act on our acquired knowledge. While the cotton flowers and blooded soil remain silent, we can now choose to either continue the conversation instigated by El Dessouki, or to ignore what has been explicitly laid out before us. At a time when the phrases “Silence Equals Violence” and “All Eyes on Gaza” will be familiar to most social media users, and public influencers exhort others that not speaking out against violence is to be complicit, El Dessouki holds a mirror to the gulf between knowledge and action. The soil’s testimony is damning. It seems, after all, the exhibition boils down to a single question: Knowledge is power, yet ignorance is bliss. Which do we choose?