A Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige retrospective spotlights a decade of the duo’s work and their commitment to uncovering lost layers of history.

In their first solo show in Beirut since 2012, Remembering the Light at Sursock Museum, Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige present almost a decade of their most recognised works, full of nuance and their signature research-led approach.

Traversing film, photography, installation and sculpture works, the exhibition takes viewers on a thought-provoking journey through history, time, poetry and the archaeological traces of the hidden worlds beneath our feet.

Having come of age during Lebanon’s civil war, Hadjithomas and Joreige often explore themes of conflict, transformation, and memory. This show, albeit presenting past works, resonates deeply with Lebanon’s current unrest, as the country slowly rebuilds following months of shelling by Israel and a tenuous ceasefire. The exhibition’s title is drawn from a 2016 video work in which the artists explored the spectrum of light underwater, showing divers swimming between the streaks of light that refract down from the surface. However, the show starts with a number of works from their ongoing Unconformities: What Lies Beneath our Feet series, which in 2017 won the Marcel Duchamp Prize.

15 x 155 x 15 cm. Installation view from Remembering the light at Sursock Museum, 2025. Photography by Christopher Baaklini.

Image courtesy of the artists and Sursock Museum

“Khalil and I like to create bodies of work that are all linked to research, and in this show there are three lines of research and bodies of work in conversation,” Hadjithomas tells Canvas. “You have Unconformities: What Lies Beneath our Feet, and the project Museum Melancholy, which is linked to the journey that we have with archaeology, geology and all that is subterranean in cities. Another trajectory [I Stared So Much at Beauty] is where we are trying to understand how poetry and art can confront the chaos that we live in and change the perspective of what is seen and what is invisible. We talk a lot about fragility and art as resistance.”

The video work Palimpsests (2017) captures both the extraction of core samples and archaeological excavations. These samples are a recurring presence through the series, symbolising forgotten urban histories. “The journey started in an unexpected way, because we went to follow a friend, an engineer called Philippe Fayad, on a construction site. He was taking core samples to analyse the soil before building,” explains Hadjithomas. “They go deep into the ground for these samples, which traverse times and layers of soil, and then place them in these boxes that are almost like rushes of time. We were intrigued and moved by this process, so started collecting the samples after they were discarded and putting them in our studio. We could see how it was telling a story that is invisible to our eyes, but we needed an interpreter and so we worked with archaeologist Hadi Choueri and other archaeologists in cities like Paris and Athens.”

This experience led the duo to think further about unseen histories being made visible, the potential narratives that could be found and the constant flux of what is known – basically, what writes history. For example, Blow Up (2025) shows reproduced and imagined traces of unearthed archaeology from around Beirut in magnifying bubbles. These show variously a reproduction of a Paleolithic worked flint and red sand, iridescent shards from a Roman ointment bottle, and the fictional traces ‘left’ from the 551 CE tsunami that destroyed ancient Beirut – a catastrophe that recorded history knows little about.

Image courtesy of the artists

As transformation is a key element of Hadjithomas and Joreige’s practice, hints of it are strewn throughout the exhibition, such as in Message with(out) a Code (2022), a series of tapestries based on photographs of archaeological finds. A State (2019) uses hundreds of superimposed images of Tripoli’s open-air dump site for unsorted waste – a new kind of urban strata – to create beautiful still-life-like images akin to paintings, transforming the waste into future traces of civilisation.

One of the most captivating pieces in the show is Under the Cold River Bed (2022), which uses three slide projector machines to deliver a series of testimonies, videos and photos about a shocking archaeological discovery in Nahr el-Bared, a Palestinian refugee camp in northern Lebanon, established in 1948. “There was a war in 2007 between the Lebanese Army and an Islamist group, Fatah al-Islam, so the Palestinian refugees had to flee. About 98 per cent of the camp was totally destroyed,” Hadjithomas explains. “The army started to remove all the rubble and archaeological ruins were discovered.” Archaeologists were able to establish that it was the city of Orthosia, a very important Roman city that disappeared with the tsunami in 551 CE.

“Suddenly you have this Roman city that is very well preserved, like a mini Pompeii, and you have these families, who have already been displaced twice, that want to come back home and rebuild the camp,” she continues. “What is the right thing to do in critical zones like ours? Do we displace the present to preserve the past? These are vertiginous questions. [In this case] they built the camp again, sealing the ruins away with a concrete slab, almost like a sarcophagus.”

Photography by Christopher Baaklini. Image courtesy of the artists and Sursock Museum

The slides – which gather viewpoints from the refugees, archaeologists and soldiers – capture the tension of the situation and the dissonant way that, despite the gravity of this discovery and the subsequent decision to leave it undisturbed for now, the event seems to have faded from collective memory. The discovery remains largely unknown – a common occurrence in Lebanon – and typical of the events that the duo love to bring to the surface, examine and reclaim.

The final section in the exhibition features pieces from the ongoing series I Stared at Beauty So Much (2016-), inspired by poets including Constantine Cavafy, Etel Adnan and Georges Seferis, which looks at how poetry can be a means of confronting disorder and finding beauty amidst chaos. A filmed interview with Adnan looks at constructed memories and narratives, delving into both her and Hadjithomas’s origins in the historically diverse city of Smyrna (now Izmir), which they have never visited, but were told about by family members. Framed by memories of grief and displacement, their perception of the city is forever skewed, verging on the imaginary.

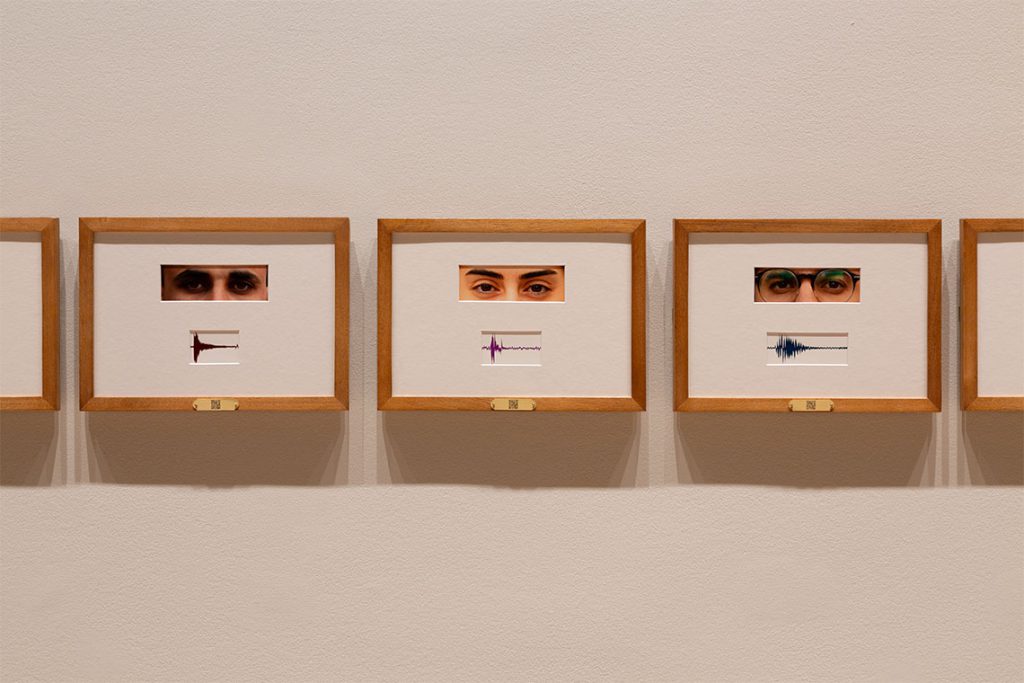

As visitors exit the show, they are given the chance to contribute the sound of their sighs to Index of Sighs (2024–), which presents several already recorded versions. Almost a form of artistic therapy, it seeks to collect a moment of heartache released in a single exhalation.

There is a certain theatrical suspension of disbelief to the show, especially the Unconformities (2016-) works, which leaves the viewer questioning what parts are real and what are imaginary – or possibly what started as one and became the other. Presented as both opposing and intertwined forces in their practice, the duo would be quick to point out that the answer might be the one you least expect.