An exhibition of artists’ books at London’s British Museum repositions a traditional format as a vehicle for art and includes works by some of the Middle East’s foremost practitioners.

A book is “a carrier of experience”, according to the Indian artist Nalini Malani. She has been making them since 1988, after finding other media too limiting. In books, her sprawling drawings can extend freely over several pages, gaining the scope to recount events from own life as well as dwell on her nation’s complex history. Her 1991 work, Dreamings and Defilings, is one of the standouts in Artists making books: poetry to politics, a showcase of artists’ books currently on show at the British Museum . “When I started to put these books together, I found that each one of them had a story to tell,” says curator Venetia Porter.

The practice of artists making books has its origins in Western Europe. One of the earliest examples is William Blake’s Songs of Innocence and of Experience (1789), in which he was able to bring his own poems to life through vividly emotive imagery. By the turn of the 20th century, the livre de peintre was gaining popularity among artists in Paris as a limitlessly creative yet practical medium that could be disseminated widely. These books were often left unbound so that each leaf could be appreciated and displayed as a work of art, not unlike a print. The lyricism of poetry lent itself naturally to the emerging art form, becoming more than just an inspiration for the artists themselves. “This isn’t simply illustration,” explains Porter. “It’s a real collaboration between the artist and poet.”

A key precursor of the exhibition, included in the first case, is André Derain’s Les Oeuvres Burlesques et Mystiques de Frère Matorel mort au couvent (1912). Here, sensitive woodcuts in the artist’s intentionally naive Fauvist style manage to recreate some of the mysticism he saw in the poem of the same name by Max Jacob. The excitement for these works became infectious and, not long after the Lebanese painter Shafic Abboud had moved to Paris in the late 1940s, he created La Souris (1954), the first of eight artists’ books he produced. His charming silkscreen prints pop with colour against the handwritten French folktale.

Although the exhibition dispenses with a strict chronological telling, its story really gets going in more recent decades, in Iraq specifically. Initially this was out of inventive necessity, as artists such as Ghassan Ghaib turned to bookmaking following United Nations Security Council-enforced sanctions that made most artist supplies tricky to get hold of. The practice, known locally as dafatir, stuck and caught on with other artists from the region, including Dia Al-Azzawi.

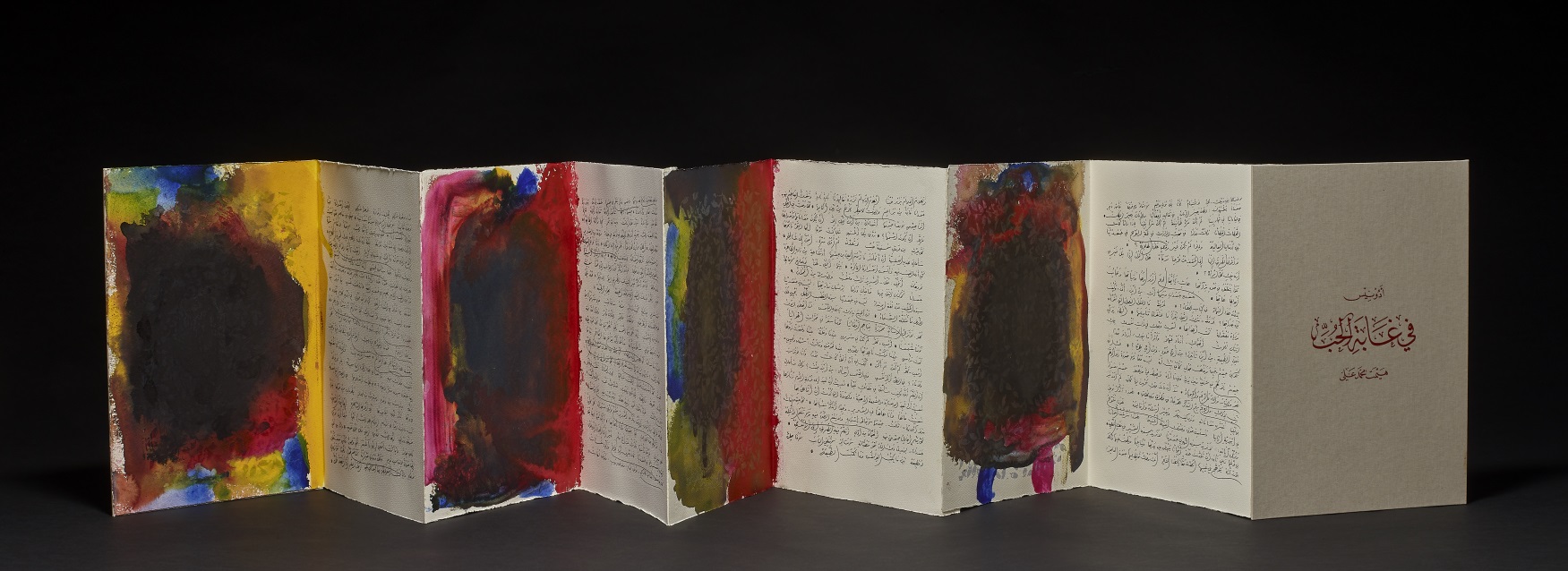

Al-Azzawi’s own assemblages often incorporate concertina-style papers that he decorates with densely colourful text and images. More than the Western examples on show, his work challenges and expands the medium, shapeshifting between a typical storybook and a sculptural artwork in its own right. In Adonis X (1990), he celebrates the iconic nonagenarian Syrian poet, otherwise known as Ali Ahmad Said, with a series of lively yet strangely ambiguous lithographs that almost steal the show. A larger collection of Al-Azzawi’s dafatir is being exhibited at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford until 11 June.

The verses of Adonis are returned to again and again by the artists with whom he often sought out collaboration, explaining in part why the production of these books has so flourished in the Middle East. “When I’ve been to Iran or some parts of the Arab world, people really know their literature in ways that we just don’t [in the West],” says Porter. “Everybody will be able to recite Hafez or tell you stories from the Shahnameh. Poetry is incredibly strong within the culture.”

Another Iraqi artist, Himat Mohammed Ali, is close friends with Adonis and a collaboration between the two produced In the forest of love (2021), in which the poet’s script is accompanied on separate pages by abstract compositions of murky, pooling paint. In an older 1999 Adonis collaboration with another friend, artist Ziad Dalloul, on the collection Kitab-al Mudun (The Book of Cities), Dalloul’s raspily etched forms feel still more ominous in monochrome.

A further comparison is Kamal Boullata’s first book, Beginnings (1992). “My main concern was how to design a graphic space that would reflect the poetry’s formal elements and serve as a tangible representation of Adonis’s poetic voice,” Boullata said. “Would it be possible to design a book in two separate halves so that the geometric whole would act as a mirror reflecting the rhythm of the poems within it?” The result is pages filled with the late Palestinian artist’s typical clean-cut patterns inspired by the angular rhythms of Kufic script, which, from across the binding, mimic – if not exactly mirror – their alternate Arabic or English translation.

Using the materiality of the book to enhance and even embody the ethereal form of literature inevitably leads to a considerable diversity of style. “[The artists] often chose the form of the book to suit the poetry,” explains Porter. With almost 50 books, each belonging to the museum’s collection, the display is animated by their eclectic medley of size, shape and material. Even though viewing such a multidimensional medium as a book in this static manner has obvious limitations, Porter points out that these works are not dusty tomes in a library but artworks, so that “even just one page is emblematic of the rest. Each page is a thing of beauty in and of itself.”

It’s important to let your inhibitions down when looking at these books. “One has to stop thinking of them as a book that you can just sit and read, but as an object,” Porter adds. One hugely compelling example is Khalil Rabah’s Dictionary work (1997), in which nails have been driven into a splayed English dictionary, allowing us only to read the definition for the word Phi.lis.tine: “inhabitant of ancient Philistia (Palestine); a materialistic person; esp. one who is smugly indifferent to intellectual or artistic values.” In this case, Rabah has “taken the book as an object to tell a very particular story. You’re not supposed to turn the pages.” The glinting nails call to mind how words can be essential records but they can also be easily weaponized.

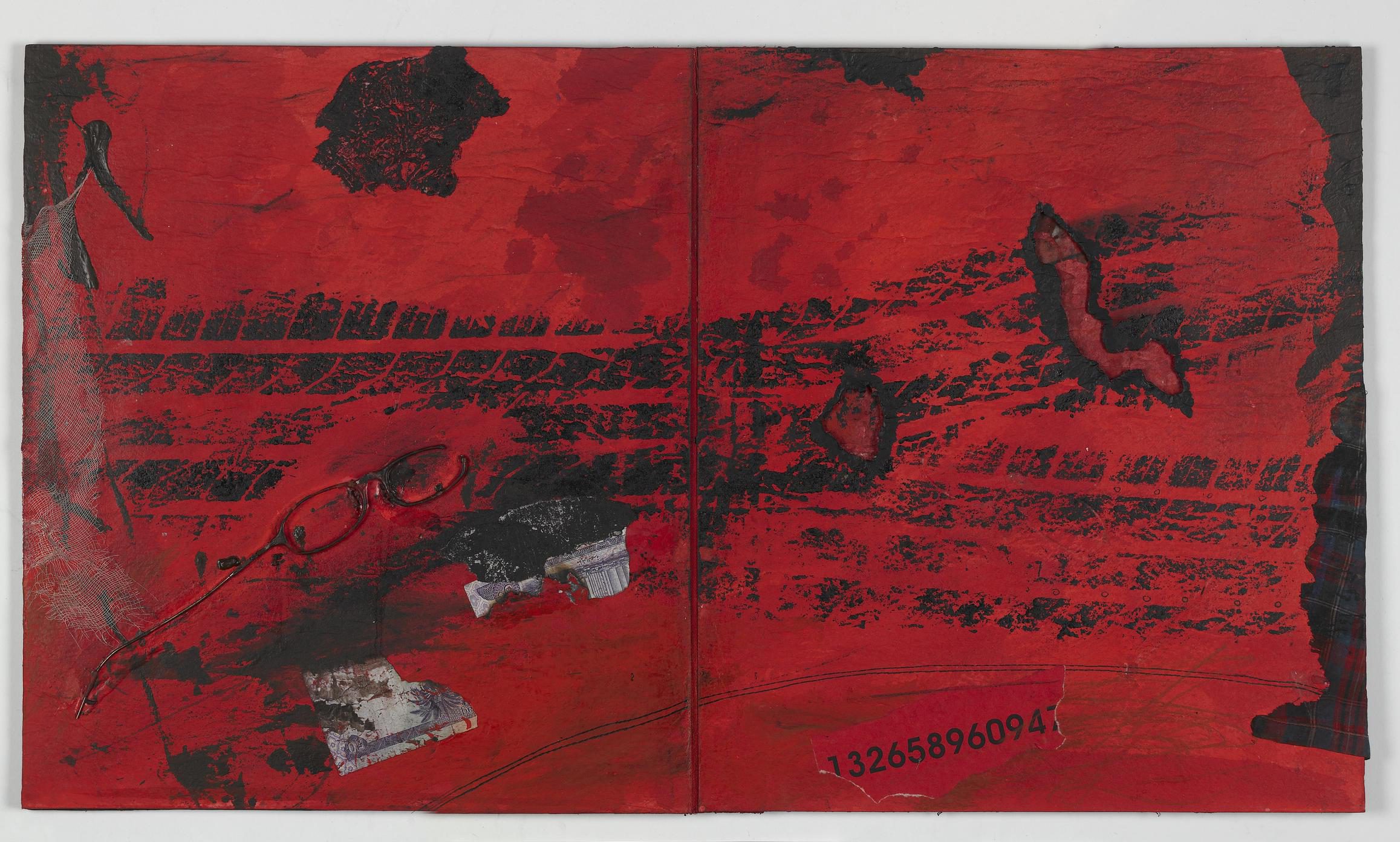

Nonetheless, the book is above all a compact and convenient document for those who have a lot to say, especially in the face of conflict, occupation, displacement and war. Iraqi artist Kareem Risan’s incandescent Every Day (2005) evokes the aftermath of war, as the red pages apparently smeared violently with blood become a ground for tyre marks, hospital gauze and fragmented passports. “I saw my city wailing under vicious bombardment,” reads the artist’s aggrieved scrawl, “its skies full of missiles, being destroyed, burned, looted, violated in all its being, details, history and structure.”

The best books in the display are able to layer meaning, as in Syrian artist and activist Issam Kourbaj’s The Damascene Collar of the Dove (2019), in which he uses a found discarded diary and fills it with disturbing contemporary images from the ongoing civil war. These have been overlaid with verses from the Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish’s ode to Damascus of the work’s same name. “It’s a palimpsest really,” says Porter. “It’s an amazingly subtle work. These books open up a fascinating world.”

Artists making books: poetry to politics runs until 17 September 2023.

This review first appeared in Canvas 106: Making Their Mark.