The Infinite Woman, a recent exhibition at the Villa Carmignac on the island of Porquerolles in the south of France, saw more than 60 artists address gender archetypes and embrace alternative visions.

Anticipation always runs high when visiting Villa Carmignac in the south of France. In part this is because of the Fondation Carmignac’s desire to do things differently when it comes to experiencing art, such as when, at the entrance, guests are invited to take off their shoes to enhance their sensory engagement with the environment. Footfall is limited and artworks are presented unframed, allowing them to be absorbed under natural light. The journey to Porquerolles – requiring several hours of travel by train, ferry and on foot – further heightens expectations.

In recent years, gender and its contemporary interpretations have been actively explored in global art exhibitions. How, then, did the Fondation’s The Infinite Woman (ended 3 November) contribute to this evolving conversation? British curator Alona Pardo brought together more than 60 artists who deconstruct traditional representations of ‘femininity’. Spanning the two floors of Villa Carmignac, the exhibition was organised into thematic zones – Of Myths and Monsters, The Sweetest Taboo, (Dis)obedient Bodies, Shape Shifters, and Dark Waters – which guided visitors through archetypes attributed to women from ancient myths to the present day.

Several key conversations emerged from the exhibition. The first two works confronted viewers with the idea that, while the image of the idealised woman has been constructed, it is also contested and ever-evolving. Botticelli’s La Vierge à la Grenade (1487) foregrounds the Virgin Mary, an archetype of the ‘ideal woman’, symbolising purity and motherhood. She clasps a pomegranate, symbolising her fertility, yet her downward gaze and passive stance reinforce the patriarchal power dynamics that have permeated Western art and culture for centuries. In contrast, Selected Wall Collages (1972–2011) by Mary Beth Edelson draws from the artist’s research into the goddess figure. Deploying her agency, Edelson remixes icons from Botticelli’s Venus to contemporary figures like Grace Jones and Michelle Obama, contesting oppressive historical representations of women and presenting alternative feminist iconography.

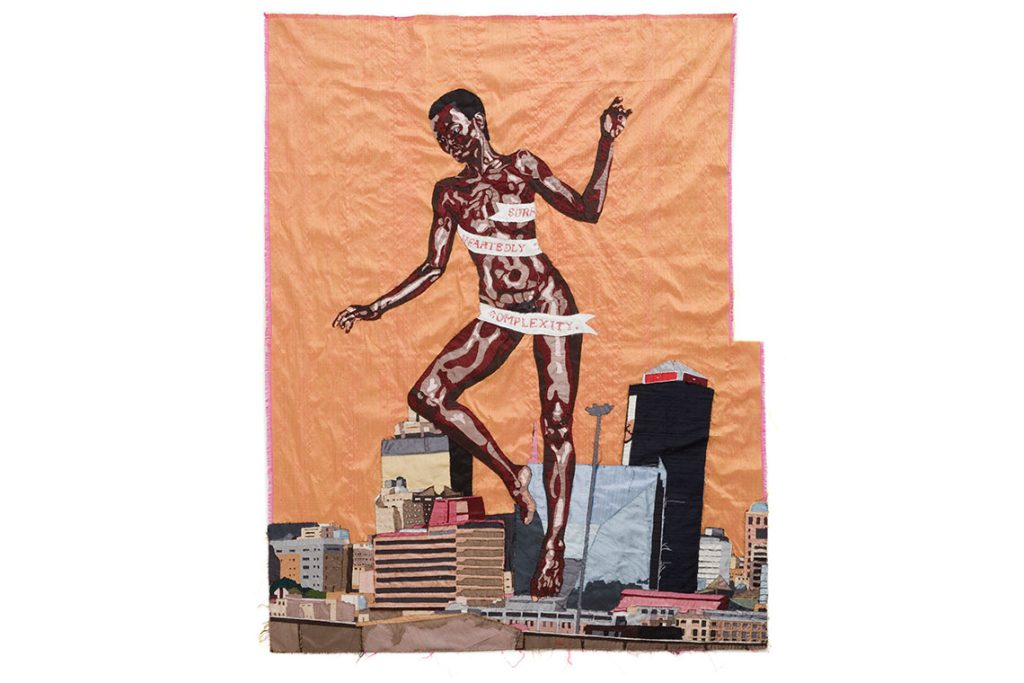

Contemporary perspectives from the Global South confronted gendered issues that are both distinct from and bound to Western narratives. Billie Zangewa’s raw silk tapestry, The Rebirth of the Black Venus (2010), engaged in dialogue with Botticelli’s iconic works, reimagining the representation of the female body in Western art history. Zangewa reclaims the image of the Black female form, portraying a nude goddess hovering above her adopted city of Johannesburg. Her hand-stitched, densely textured composition offered an arresting alternative to Botticelli’s alabaster-skinned Venus, while simultaneously addressing the historical exploitation of Sarah Baartman – a Khoikhoi woman taken from southern Africa and exhibited as a freak show under the name ‘Hottentot Venus’ in nineteenth-century Europe.

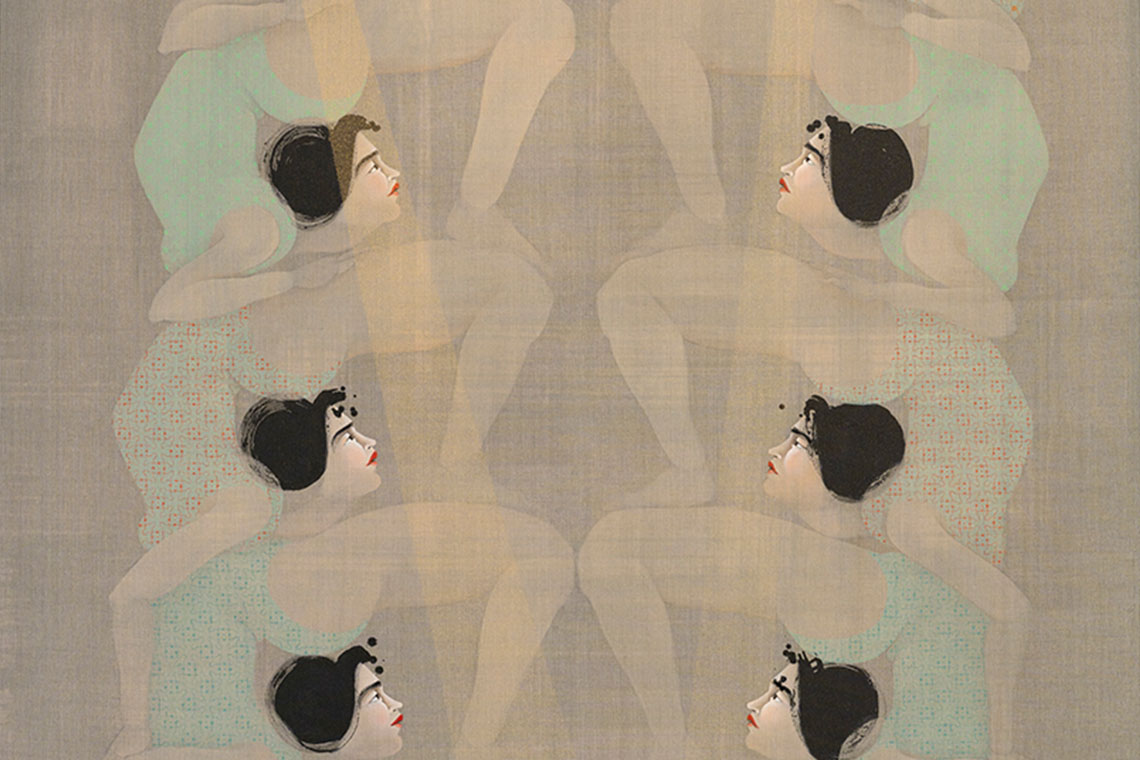

Nearby, Iraqi-American artist Hayv Kahraman’s Giving Birth to a Mortar (2021) evoked the dark mother archetype. Here, two naked women are entangled in a rope that could be interpreted as either an umbilical cord or their hair. One births a mortar, a weapon made familiar to Kahraman during her youth in Iraq. These figures play in the space between destruction and transformation, life and death, drawing parallels between literal war and the wars waged on women’s bodies.

The use of textiles as a form of feminist subversion and resistance appeared in various guises across the exhibition. Techniques and materials traditionally associated with the domestic sphere were employed to critique gendered labour and the divisions that have historically marginalised textile work, both socially and within the art world. A central figure in advancing social change for women, feminist artist Judy Chicago’s purple batik, Childbirth in America: Crowning Quilt 7/9 (1982), from her seminal Birth Project series (1980–85), depicts the crowning head of a child emerging like solar beams from the mother. The work, imbued with explosive energy, evokes the force and power of women.

© Billie Zangewa

The idea that women should enjoy their bodies and autonomy was echoed in the work of Cairo-born artist Ghada Amer. In Your Silence (2023), Amer draws on the Egyptian appliqué technique khayamiya, traditionally practised by men. By abstracting a line from Audre Lorde’s essay The Transformation of Silence into Language and Action (1977), Amer transforms barely legible script into a visual declaration against the ongoing silencing and exploitation of women. Set against the backdrop of social movements like #MeToo and the revocation of Roe v. Wade in the USA, her work transcends contexts, emerging as a rallying cry for women’s rights and the amplification of their voices.

Within a fleshy pink cavern, a series of tactile, hand-tufted pieces by Ukrainian artist Anna Perach connected history, space and contemporary gendered narratives. Her freestanding sculpture The Hysteric (2023) was particularly striking; the artist reinterprets Hans Baldung Grien’s sixteenth-century print, Seated Woman Defecating (1513), depicting an elderly nude witch using chunks of pastel blue and pink yarn. The figure’s shaking hand evokes the image of ‘hysterical’ women confined to Parisian asylums. Surrounding it, three vibrant wearable corsets from her Mother of Monsters (2022) series bubbled with historical and medical references, alluding to how women’s bodies have been pathologised and demonised over time.

References to female anatomy were rife, suggesting that women often feel reduced to their body parts; Alina Szapocznikow’s Lampe Bouche (1966) captures this sentiment. Her disembodied casts of the female form – here, a pair of glowing lips – functioning as a desk lamp feel both playful and jarring. The work nods towards Pop Art’s joyful visual language while drawing from the subversive codes of Surrealism. Szapocznikow’s engagement with unconventional materials like resin, rubber and polyurethane re-conceptualized sculpture as an intimate record of her gendered body and the discourses imposed upon it.

Throughout the exhibition, artists harnessed the visual language of oppression, whether through textiles, weapons or hair. The latter in particular was a recurring motif, engaged by artists as a symbol of rebellion, seduction or social control. In Julie Curtiss’s painting, Bathsheba (2021), two women receiving a pedicure summon the biblical story of Bathsheba, where the male gaze becomes a tool of violent oppression. Drawing from Surrealism and Pop Art, Curtiss subverts this gaze, depicting her female figures as entirely composed of hair, raising questions about beauty, control and the constraints of femininity.

Leaning ominously against the back wall was Rosemarie Trockel’s Notre-Dame (2018), a 2.9-metre-long, black, steel hairpin. This monumental piece carries layered symbolism, representing both control and liberation. The hairpin, traditionally used to tame and constrain an aspect of the female body, expresses societal expectations of ‘proper’ femininity – a notion reinforced by the work’s title, which references the Parisian cathedral dedicated to the Virgin Mary. But the hairpin also functions as a weaponised emblem of resistance against patriarchal norms, symbolising a tool that enables women to reclaim agency, allowing them to move freely and participate fully in their social worlds.

The Infinite Woman offered much to reflect on, stirring a range of emotions and critical insights. It encouraged us to reflect on how women have been depicted and oppressed throughout history while creating space for reimagining roles, female resistance and the dismantling of constricting narratives. But it also left a lingering sense of frustration – frustration that, despite the work of pioneers like Chicago and Szapocznikow decades ago, women today must still contend with how they are framed, oppressed and objectified, continually having to justify their realities and desires in ways that male artists do not.

The inclusion of works like Picasso’s Femme Nue Couchée Jouant Avec un Chat (1964) also raises an important question: can women artists truly advance new narratives when their work is positioned next to the figures that perpetuated problematic representations of women? Beyond challenging these tropes, what alternative visions of womanhood are being brought forward? What else? What more? What new narratives and accomplishments are emerging that break free from the limitations of past representations? I found myself wanting to see more of these aspects – more anarchy, and more future-facing depictions of womanhood that transcend the confines of history.